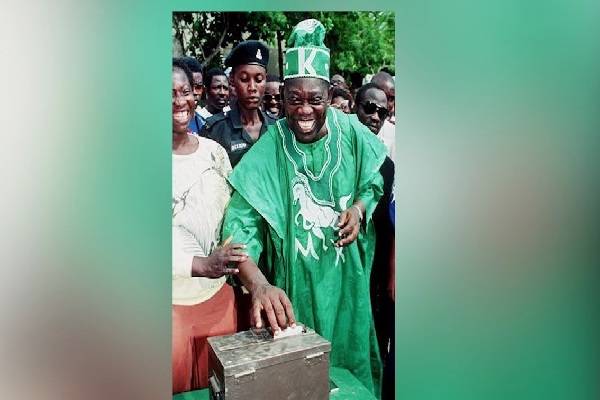

Ghana’s Vice-President Mahamudu Bawumia has conceded defeat in Saturday’s elections, congratulating opposition leader and former President John Mahama on his victory. Early results suggest this could be one of the heaviest defeats in decades for the New Patriotic Party (NPP), which had been in power since 2016.

Voters were angered by a combination of the rising cost of living, a series of high-profile scandals and a major debt crisis that prevented the government from delivering on key promises. As a result, the NPP may have dropped below 45% of the presidential vote for the first time since 1996.

Ghana’s vote brings to an end a remarkable 12 months in African politics, which have seen five transfers of power – more than ever before. This “annus horribilis” for governments has now also brought opposition victories in Botswana, Mauritius, Senegal and the self-declared republic of Somaliland.

Even beyond these results, almost every election held in the region this year under reasonably democratic conditions, has seen the governing party lose a significant number of seats.

This trend has been driven by a combination of factors:

• the economic downturn

• growing public intolerance of corruption and

• the emergence of increasingly assertive and well-co-ordinated opposition parties.

The trend is likely to continue into 2025, and will cause trouble for leaders such as Malawian President Lazarus Chakwera, whose country goes to the polls in September.

One of the most striking aspect of the elections that have taken place in 2024 is that many have resulted in landslide defeats for governments that have previously appeared to have a strong grip on power – including in countries that have never before experienced a change at the top.

The Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) that had ruled the country since independence in 1966 was crushed in October’s general elections.

As well as losing power, the BDP went from holding 38 seats in the 69-strong parliament to almost being wiped out.

After winning only four seats, the BDP is now one of the smallest parties in parliament, and faces an uphill battle to remain politically relevant.

There was also a landslide defeat for the governing party in Mauritius in November, where the Alliance Lepep coalition, headed by Pravind Jagnauth of the Militant Socialist Movement, won only 27% of the vote and was reduced to just two seats in parliament.

With its rival Alliance du Changement sweeping 60 of the 66 seats available, Mauritius has experienced one of the most complete political transformations imaginable.

Senegal and the self-declared republic of Somaliland also saw opposition victories.

In the case of Senegal, the political turnaround was just as striking as in Botswana, albeit in a different way.

Just weeks ahead of the election, the main opposition leaders Bassirou Diomaye Faye and Ousmane Sonko were languishing in jail as the government of President Macky Sall abused its power in a desperate bid to avert defeat.

After growing domestic and international pressure led to Faye and Sonko being released, Faye went on to win the presidency in the first round of voting, with the government’s candidate winning only 36% of the vote.

Even in cases where governments have not lost, their reputation and political control have been severely dented.

South Africa’s African National Congress (ANC) retained power but only after a bruising campaign that saw it fall below 50% of the vote in a national election for the first time since the end of white-minority rule in 1994.

This forced President Cyril Ramaphosa to enter into a coalition government, giving up 12 cabinet posts to other parties, including powerful positions such as home affairs.

The recent elections in Namibia told a similar story.

Although the ruling party retained power, the opposition has rejected the results and claims the poll was badly manipulated after it was marred by logistical problems and irregularities.

Even with the flaws, the government suffered in the parliamentary election, recording its worst-ever performance, losing 12 of its 63 seats and only just holding on to its parliamentary majority.

As a result, a region that is known more for governments that manage to hold on to power for decades has seen 12 months of vibrant, intensely contested, multiparty politics.

The only exceptions to this have been countries where elections were seen as neither free nor fair, such as Chad and Rwanda, or in which governments were accused by opposition and rights groups of resorting to a combination of rigging and repression to avert defeat, as in Mozambique.

Three trends have combined to make it a particularly difficult year to be in power.

In Botswana, Mauritius and Senegal, growing citizen concern about corruption and the abuse of power eroded government credibility.

Opposition leaders were then able to play on popular anger at nepotism, economic mismanagement and the failure of leaders to uphold the rule of law to expand their support base.

Especially in Mauritius and Senegal, the party in power also undermined its claim to be a government committed to respecting political rights and civil liberties – a dangerous misstep in countries where the vast majority of citizens are committed to democracy, and which have previously seen opposition victories.

The perception that governments were mishandling the economy was particularly important because many people experienced a tough year financially.

High food and fuel prices have increased the cost of living for millions of citizens, increasing their frustration with the status quo.

In addition to underpinning some of the government defeats this year, economic anger was the main driving force that triggered the youth-led protests in Kenya that rocked President William Ruto’s government in July and August.

This is not an African phenomenon, of course, but a global one.

Popular discontent over inflation played a role in the defeat of Rishi Sunak and the Conservative Party in the UK and the victory of Donald Trump and the Republican Party in the United States.

What was perhaps more distinctive about the transfers of power in Africa this year was the way that opposition parties learned from the past.

In some cases, such as Mauritius, this meant developing new ways to try and protect the vote by ensuring every stage of the electoral process was carefully watched.

In others, it meant forging new coalitions to present the electorate with a united front.

In Botswana, for example, three opposition parties and a number of independent candidates came together under the banner of the Umbrella for Democratic Change to comprehensively out-mobilise the BDP.

A similar set of trends is likely to make life particularly difficult for leaders that have to go to the polls next year, such as Malawi’s President Chakwera, who is also struggling to overcome rising public anger at the state of the economy.

With the defeat of the NPP in Ghana, Africa has seen five transfers of power in 12 months. The previous record was four opposition victories, which occurred some time ago in 2000.

That so many governments are being given an electoral bloody nose against a backdrop of global democratic decline that has seen a rise in authoritarianism in some regions is particularly striking.

It suggests that Africa has much higher levels of democratic resilience than is often recognised, notwithstanding the number of entrenched authoritarian regimes that continue to exist.

Civil society groups, opposition parties and citizens themselves have mobilised in large numbers to demand accountability, and punish governments that have failed both economically and democratically.

International governments, organisations, and activists looking for new ways to defend democracy around the world should pay more attention to a region that is often assumed to be an inhospitable environment for multiparty politics, yet has seen more examples of democratic bounce-back than other regions of the world.

BBC