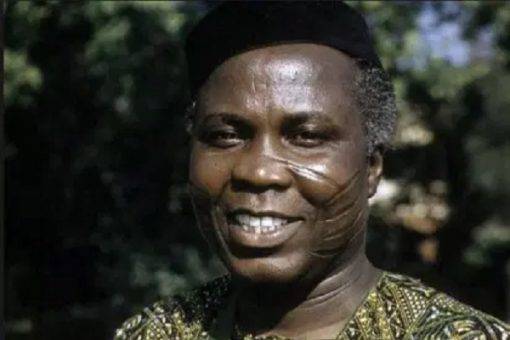

It is 60 years ago on the morning of January 15 when Chief SL Akintola was murdered on the grounds of the premier’s residence in Iyaganku Reservation, Ibadan by Captain Okoro and soldiers apparently from the military cantonment in Abeokuta who having kidnapped the deputy premier, Chief Remi Fani-Kayode, led him to accompany the murderers to the premier’s lodge. Chief Akintola refused to surrender after the initial fuselage of the soldiers.

It is said the premier decided to come into the open space where the troops killed him. While this was going on in Ibadan, the premier of Northern Nigeria, Sir Ahmadu Bello had also been killed by troops led by Major Chukuma Nzeogwu Kaduna. His wife was not spared. The commander of the 1st division of the army, Brigadier Samuel Adesujo Ademulegun with his eight months old, pregnant wife were killed in their bedroom by troops led by Major Timothy Onwuategwu while their little children watched what was happening. The second most important military man in Kaduna, Colonel Ralph Shodeinde was also killed in his house.

Action was extended to Lagos where the military commander, Brigadier Muhammad Maimalari was killed by troops led by his Brigade Major, Emmanuel Ifeajuna. Some detachment of troops kidnapped the Prime Minister Sir Abubakar Tafawa Balewa and his Finance Minister, Chief Festus Okotie-Eboh and took them to some distance on the Abeokuta-Lagos road where both were murdered and their bodies were found a few days after January 15.

The military action was first welcomed in Nigeria, particularly in the southern part of the country where bitter politics seemed to have been the order of the day. When later the coup d’état was subject to critical analysis, the ethnic and regional dimensions became obvious, that it was a political struggle for power rather than using the vote that resorted to the use of bullets.

In the Western part of Nigeria where Chief Akintola was premier, the coup was celebrated as a relief from the political chaos. The genesis of the problem was the collapse of the ruling Action Group due to ideological cleavage and external manipulation by rival parties from other regions.

This presented an opportunity to destroy the West and the Action Group. The NCNC that was predominantly led by the Igbo had coalesced in the centre with the predominantly Hausa party to form the federal government to monopolise power and used it to corner appointments which Chief Akintola loudly condemned.

Getting rid of Akintola became a matter of urgent necessity because he, and first the Action Group before its breakup in 1963, had become a troublesome presence to the federal authorities. The vitriolic demonisation of Akintola by the combined NCNC and the federal government which eventually went its different ethnic ways after the federal election of 1964 during which Akintola’s political tentacles held sway in Western Nigeria when his message of inclusiveness of the constituent ethnic groups needed to be represented in the federal government began to resonate with the people.

When the Western Nigerian elections came up in 1965, it became a “do or die” election for the two rival political formations in Nigeria namely the UPGA, formed by the remnants of the NCNC in the West, and their big Eastern faction and the Awolowo strong faction in the West and Lagos. Confronting them was the NPC juggernaut from the North and the Akintola faction of the Yoruba political machine.

The various Nigerian minorities were split between the two groups. In this situation the election could hardly be free and the Akintola government in the West did not play the electoral politics by the books. After the election that returned Akintola to power, rioting and rebellion broke out throughout the Western Region and Lagos. It seemed to critical observers that unless serious use of power was employed, the government would have to open negotiations for power sharing in the West.

There were rumours of troops movement and when the coup d’état of January 15, 1966 happened, it did not come to critical observers as a surprise; nevertheless it was welcomed globally with sadness because our country had a lot of promise.

When Akintola was killed 60 years ago, he died for his belief in inclusive government and that in spite of whatever ideology we embrace, the government of the people for the people shall prevail. His remains that had been deposited in Adeoyo Hospital following his death were taken mainly by Ogbomoso people under the leadership of Prince Laoye, for burial.

What remains of Akintola’s legacy?

Though time is a healer, the evergreen memory of Akintola remains forever for his family and political associates and for Nigerians who now appreciate him for some of his ideas.

He was one of the founders of the Action Group which was one of the political parties that fought for the independence of Nigeria. When the country became independent in October 1, 1960, he was premier of the Western Region, the most financially prosperous and infra-structurally advanced part of the Federal Republic. Right from the formation of the Action Group, he stood out as a federalist as against the NCNC of Nnamdi Azikiwe who stood out for a unitary government. Awolowo had captured the feeling of the Yoruba in 1947 when he wrote his book Path to Nigerian Freedom and argued that there were no Nigerians as there were Frenchmen, Germans or Japanese and that Nigeria was simply a geographical expression. Akintola had said this much earlier when he was editor of the Lagos-based Daily Service. Akintola had used his position as an editor in the 1940s well before the formation of the Action Group to oppose Azikiwe’s dream of united Nigeria and had agreed with what Abubakar Tafawa Balewa was to say later that united Nigeria was “British intention” for the country.

Akintola was a realist. He had lived in the North as a young man and he spoke Hausa fluently and understood the traditions and mores of the Hausa and held the view that they were totally different from those of the Yoruba despite the fact that the religion of Islam was embraced equally by about 50 percent of the people just like the Hausa. He also saw the Igbo culture of village democracies with little respect for a hierarchy of chiefs and elders and kings being totally alien to the Yoruba but he felt whatever differences existed in the country could be harmonised under a federal structure of government. He found a common ground in the belief in a federal structure with the Hausa Fulani leadership.

He regarded the federal constitution that took us to independence as not protective of regional autonomy enough. Indeed it was he who moved the successful motion of independence in 1957 after the defeat of the earlier one moved by Chief Anthony Enahoro in 1953.

Akintola’s struggle between 1962 and 1966 can be explained in his struggle for inclusivity in government at the federal level as well as respect for state autonomy. Unfortunately the struggle also included peaceful survival of his government at home which he did everything to protect despite war declared on his state by people from outside until it became a case of all things were fair in war. After all, he was the Are Ona Kakanfo of Yoruba land.

Both Awolowo and Akintola families had been friends for a long time and are still friends even today even though supporters are still crying more than the bereaved! His embrace of northern power structure was based on political realism rather than just surrendering to forces arraigned against him and what he considered against Yoruba interest.

For anybody interested in the development of Nigerian language, Akintola comes before everybody. His mastery of English, Hausa and Yoruba makes him a natural nationalist in the struggle against British imperialism and for the soul of Nigeria. He was a liberal in the full meaning of the word. As Sir John Rankine, the last British governor of colonial western Nigeria said of him, Akintola was a master of ambiguity arguing issues from two opposing sides convincingly. The governor apparently forgot Akintola was a successful lawyer in Lagos before going into politics after years of teaching at Baptist Academy in Lagos, following these by years as editor of a successful newspaper. He was so much in control of the Yoruba language that many people in the university community felt his service as an exponent of the Yoruba language would have been more rewarding than the thankless engagement in politics.

He was also a practicing Christian who avoided violence as much as much as possible. Some hot heads in his party used to openly tell him that Fani-Kayode would have done a better job in putting down the rioting and rebellion in Yoruba land in 1965 following an election which the people felt was rigged in favour of the premier’s party.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy is his idea of inclusivity because he believed you must have a country first and a people who felt they have a stake in the country before practising whatever ideology that was fashionable at the time.

The above is part of a brief talk delivered at the University of Ibadan Conference Centre.