At the beginning, Rabiu Kwankwaso was the beautiful bride. Suitors dangled everything, from flattery to a paradise to a handsome bride price. Unimpressed, the coquet at once played the ostrich and the peacock.

He was in a vertigo of suitors’ attention. He craved the headlines, and he saw himself as the second beautiful bride in our political history and the one of this generation

he first was the Owelle of Onitsha, the great Nnamdi Azikiwe, who anointed himself in the Second Republic as the beautiful bride. The major parties drooled and wooed him.

The beautiful bride has woken up to observe that, right under his flamboyant wings, the suitors’ eyes caught a vision.

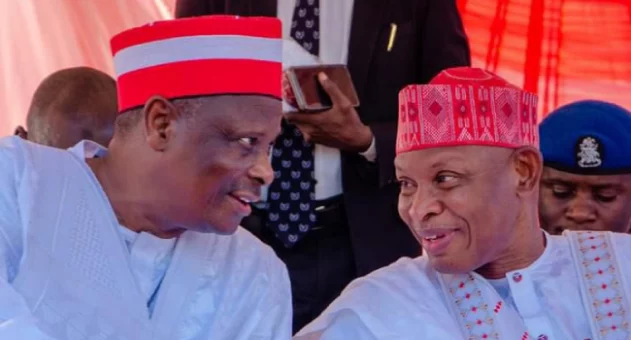

Suddenly, Kwankwaso became a faded entity. The new beauty is Abba Yusuf. The man of the Kwankwasiyya movement is like Shakespeare’s scorned woman whose fury is like a burning hell.

Critics who are yelling one party have lost the point. They say Yusuf has betrayed his in-law, that he was an ally for decades, that he made Yusuf governor, that if this is what in-laws are made of, why marry! To fuel that sentiment, Kwankwaso adds that he led him like a sheep to knock on the doors of Supreme Court justices.

So, it was clear that the leader of the NNPP is in sour mood. So sour he has sullied the temple of justice. That assertion alone is the death knell of the former Kano governor’s political career. Whether he met the justices or not, humans are likely to believe him. We prefer sensations to facts. Kwankwaso has revealed himself as a tattle tale of politics, a pariah who can rat when facts are sacred, an oddball in a cult. Who will commune with him, or whisper a code to his ears or lead him to the spot of the cadaver’s stench?

This is at the root of the story of Governor Yusuf’s defection. The real victim is Mallam Aminu Kano, the man who made Kano a community. His travail gave birth to the talakawa as we know them today in the north, especially in Kano. We hear of Kwankwasiyya movement today as though it is the continuation of the Aminu Kano crowd.

What we have today is an imposture. The poor and neglected masses of the city want the heart and brio of their man of NEPU and PRP. Kano politicians have always seen it. They see their alienation, their lack of food and shelter, their lack of education and infrastructure. Kwankwaso never started in the mould of Kano’s talakawa politics. He was of the conservative sort. He supped with the PDP after flirting with Shehu Yar’adua.

He saw his opportunity and made a pirouette into a son of Aminu Kano. The thing, though, is that he is a son that never credits the father. He hardly invokes mallam’s name.

He tapped into the temper of the people. They famished for cheer, so he gave them a song. They wanted political orchestra, and he offered them a dance. He gave them enough to eat to want another dinner. He projected the theatre of Aminu kano but not the plot and character. Aminu Kano was ideological. He was a descendant of Marx and Lenin, and he taught the people to shun the feudal hierarchs of the north. He loathed the acquisitive bravura of the peacock class, their mania to con the people and ride them to power and personal glory. He wanted to empower the little guy and girl, to make them own their own society.

Mallam Kano told them that religion was no excuse for poverty or to be starched into a lower class. No one is destined to a subordinate citizenship. Mallam Kano was himself a member of the Northern People’s Congress (NPC), the party that perpetuated the status quo. Mallam Kano rebelled against its suffocating mantras and certainties. He was shown the exit.

If Mallam Kano left the party because he could not reform it, others came to Kano’s house because they could exploit it. They were not believers. They saw it as a key to the door of personal enrichment and glory. One of them was Abubakar Rimi in the Second Republic under the People’s Redemption Party (PRP). Rimi was a colourful opportunist, a sometimes bombast and ideological harlot who brandished doctrinaire epithets. He ran against Kano’s ideological pricks, and he lost his re-election bid under a conservative party, The NPP.

The man who stuck with Mallam Kano was Balarabe Musa, Rimi’s counterpart in Kaduna. Balarabe was an ideologue, a faithful who lacked cunning.

He believed to a fault. He had faith without works. He did not understand that to operate as a bigot can earn you applause but not result. Even a little victory for your cause may elude you. Just like Thomas More of England in the era of Henry the Eighth who did not know the value of a little negotiation. He had the street but not its joys. When Robert Bolt wrote the play A Man for All Seasons, he was not really applauding More but exposing the quarries of belief. Mallam Kano, for all his ideological firebrand, was no purist. He even lined up for an alliance with Awo and Zik against the NPN. As the scriptures say, “here a little, there a little.”

When this republic arrived, the masses famished for cheer. Enter Kwankwasiyya. His is not an ideological movement but an emotional one. Sentiment, said Oscar Wilde, is more important than reason for humans. Kwankwaso exploited that gap. As Poet Lord Byron noted in his Don Juan, “You’d best begin with truth, and when you’ve lost your labour, there’s a sure market for imposture.”

The original flavour of the movement was lost to a number of factors. One, Mallam Kano did not groom a worthy successor. He had two men, one was a fake and even a rake, and the other was a stiff neck. Two, Marxism gradually became passe as an idea that has been disgraced in public as something we must adore at the expense of human self-regard, apologies to Roger Rosenblatt. The French thinker Francois-Rene de Chateaubriand warned of three stages of movements: utility, privilege and abuse. Rimi marked its age of privilege and Kwankwasiya the age of abuse.

So, those who are not happy with Abba Yusuf should note that there was not a high conscience in the house Kwankwaso built. Rather he invited a bulldozer in the form of Governor Yusuf, and what did you expect from a bulldozer? So, what we have is a sort of parricide. The godfather was bulldozed. A bulldozer may begin with physical structures. But the more sublime one would come at last. The first bulldozer, though, was the accumulation of men like Rimi and Kwankwaso who had taken down the Mallam Kano edifice.

Abba Yusuf bulldozed the spirit. The Kano governor did not betray, there was nothing in the home. He left a carcass in the light of Mallam Kano. This is different from the story of the Brothers Karamazov, a novel by Fyodor Dostoyevsky. The sons wanted the father dead, and even though they did not kill him, one of them said, “of my father’s blood I am not guilty… I wanted to kill him, but I’m not guilty. Not me.” That was in court. In private, guilt writ large. The other sons took the guilt because in their hearts they had committed parricide. They did not commit to it but they committed it. It was not so much an oedipal as Kafkaesque innocence. In the case of Mallam Kano, they wanted him dead and they saw to it, piecemeal. Did we hear mallam’s ghost whisper to Governor Yusuf: It’s time to go.