By Sam Omatseye

The terrible thing about IBB last week was that we allowed him to be Maradona again. The headlines last week said it all. They said the former military president regretted his actions in annulling the June 12 poll.

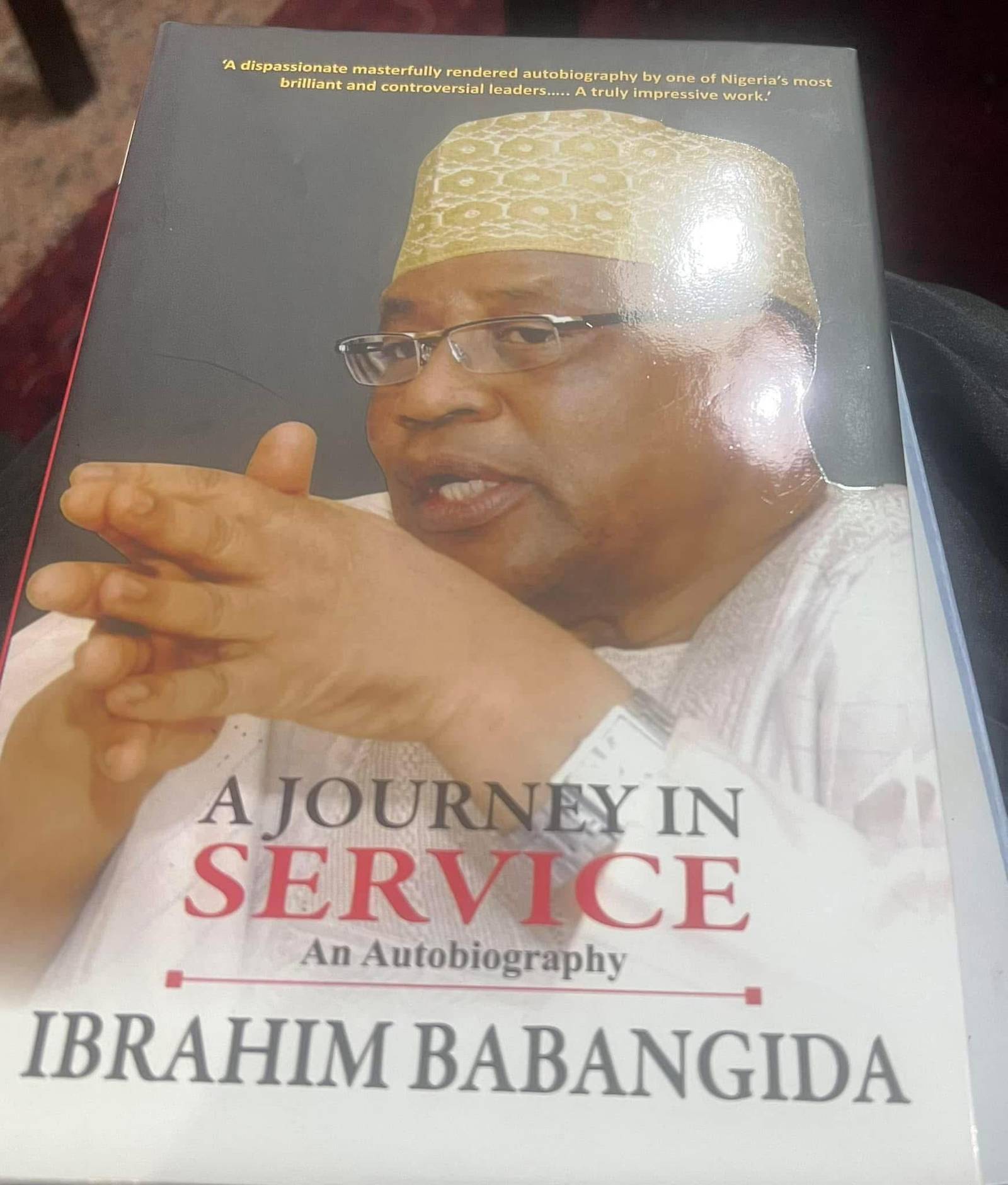

If you read the book, A Journey In Service, An Autobiography, and if you heard his short speech at the book presentation, Ibrahim Babangida never once said or even suggested that he regretted it. He described it as regrettable, which means we ought to lament his shameless action. That does not amount to a personal regret.

He also said: “The nation is entitled to expect my impression of regret.” A tongue-twister. That does not mean he regretted it. The expression was a trap, and editors, reporters, commentators and even the political class fell into it. He indeed conned journalism.

For you to regret, we expect remorse. There was no remorse in the diction and tone of his delivery. It was a cold-blooded offering. You need remorse to apologise. To regret is to be unhappy about what one has done to oneself. Remorse means you are pained for hurting others. He did nothing of that. We climbed a high moral pedestal believing he asked for mercy. He asked for no such thing.

IBB was Maradona again, and he conned many with his rhetorical rigmarole. I don’t like him but I admire the man. He came to laugh at the nation, and at the end of that dark cackle, he carted home a profit. If he said, we are “entitled to expect my impression of regret,” he merely said it is your right to ask me to say I am sorry, but it is my choice not to say it. I cannot give you the throat to gloat, to wrest judgment, to humiliate me as a groveling sinner. I will never flatter your moral superiority.

He boasted that he conducted the best election. That was his point. He knew Abiola won. His opinion was worthless. Buhari has declared it, and M.K.O. Abiola has earned GCFR. IBB gave us a meal, a poisonous meal, but no mea culpa. His confession adds nothing to the June 12 value. It was just a saga of a man – IBB – trying to be heard, when all ears were deaf.

Then he said he took full responsibility. He said, he would do it differently, if he had the chance again. How differently? Many, including the reviewer Prof. Yemi Osinbajo, implied he would have allowed Abiola be president. The same Abiola he said in the book would not be a good president? The same Abiola he paraded Yoruba topmen, including the Ooni of ife, to see his contracts with government, his government? The Ooni yelled, “Ohun nikan la s’aiye fun ni?” Was the world made for him alone?

Doing things differently surely did not include Abiola restoration. After that assertion, he said he did it in the best interest of the country. It means annulling June 12 was in the best interest of the country. Restoring it was not. It was a binary choice? He chose the path of perdition. He just told us that, in June 1993, the best action was to annul. He even gloats that his action was right because democracy has prevailed over disintegration.

If you read the book, you could hear IBB’s voice. For those who were alive when he was president, and listened and studied his speeches, there is nothing different now. The writers then may be different from the editors like Dr. Yemi Ogunbiyi and Dr. Chidi Amuta, yet the voice is inescapably IBB’s. In his style, he projects the air of the learned, but that is because he knows how to pick brilliant men. Who would go wrong with Amuta, Ogunbiyi, et al? But he has a native cunning, an earthy brilliance, a street wisdom, and an ability to appear to grasp concepts like a sponge. We saw it when he was military president. We see it now. He was a dangerous man and he exploited the air of macabre augury around him.

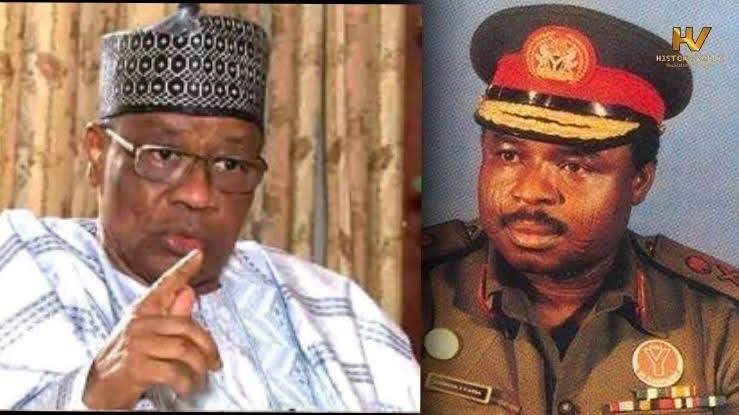

Some have called him a coward when he blamed Abacha. He cannot defend himself. Maybe his people can. Even if they do, it will all be speculative. Sophocles wrote. “The dead will never testify against a burial.” Cowardice is an elementary, if naïve, charge. A dictator is, by definition, a coward. Such a claim says nothing new. History has a list of such despots. Pol Pot, Mussolini, Kurunmi, Caligula, Nero. They are impotent without arms and state power. But Babangida is a special kind of coward. It is a special kind of coward who stakes his life in coup after coup. It is a coward who was shot at during the civil war, flown to Lagos, rejected a surgery, recovered and was not afraid to return to battle. It takes a special kind of coward to go upstairs in a radio station in Lagos to meet with coup leader Buka Dimka without any arms. His boss T.Y. Danjuma ordered him to return and flush him out.

He did not fear court martial as implied in Alabi Isama’s book, The Tragedy of Victory. Isama wrote that IBB asked Dimka to drop his weapons and run. IBB writes that he “inescapably” escaped. It takes more than a coward to dare Idiagbon with a coup attempt. It took more than a coward to sit at his office on the top floor of the Defence Headquarters in Lagos when virtually every soldier was running for their life out of the building over a bomb scare but IBB remained ensconced and unfazed in his office. This is not his story, but Debo Bashorun’s account in his anti-IBB book, Honour for Sale.

One thing I wanted to read was his use of decree two. He gave himself plaudits for abrogating Decree 4 but says nothing of Decree 2. Four was a subset of two. Rather, he undertakes a phony intellectual rollercoaster trying to frame a human and democratic system. He says nothing about the deaths he piled up during the June 12 turmoil, the hounding of radicals, the many dead on street protests, the long disruptions of life, the destruction of the economy, the high-profile deaths like Kudirat Abiola, Bagauda Kaltho, etc. There was no mention, not to say regrets or even a funereal tone on the deaths he unleashed.

The health challenges that ultimately took the lives of Gani Fawehinmi and Beko Ransome-Kuti derived from jail times under his gulag. I remember as the managing editor of the Concord Newspapers’ Abuja bureau, I was sitting on my desk when our Villa correspondent Mohammed Adamu walked in with what looked like a scrap of a paper. It had no letter head, no signature, no government insignia. He told me Chief Press Secretary Nduka Irabor gave it to him and other correspondents. I read it, and its writing bore IBB’s serpentine style. It did not say directly that the election was annulled, but it implied it. I called the editor of National Concord, Nsikak Essien. He asked me to call the editor-in-chief, Dr. Doyin Abiola. She asked what it all meant, as though she did not understand it. I explained that the election had been annulled. As the wife of the winner, the hope of a life in the villa held the prospect of a fantasy. She became angry with the messenger, and said I should have scooped this earlier.

I was in the joyous halo of my birthday, but history decided to mock. IBB says, it was Abacha’s men who did it. We need Nduka Irabor to let us know if his boss, Admiral Aikhomu, did not know about it. IBB said Aikhomu was taken aback by the letter.

IBB said he knew nothing about Arthur Nzeribe’s Association for Better Nigeria (ABN) that mobilized a circus for annulment. He did not know about Justice Ikpeme’s decision about the June 12 poll. He felt helpless about stopping the group, yet he banned newspapers, hounded human rights group like CDHR and CLO, and the Campaign for Democracy and NUPENG’s Frank Kokori. He locked up Beko and Falana, and I remember seeing them in court and even following them to know where they were kept until a soldier pointed a gun and asked me to go back. IBB and his men did not even stop his SSS men from following me around Abuja. I did not know until Abiola’s first aide, Olu Akerele, hinted me that two cars, a Jetta and 505, took turns following me about town. The same IBB who boasted as though inebriated that “we are not only in office but in power.” He knew when now President Bola Tinubu, Olisa Agbakoba, and editors of The News and Tell magazines, were staked out day and night. Fearless reporters like Alex Kabba were hunted out of the country. Yet, ABN puffed on the streets and IBB could do nothing?

The most fascinating was his telling of his life at 14. His father died, and he was so distraught that he wanted to join the army. The now orphan boy was dissuaded by his relations. But for a boy whose mother lost child after child, including twins, and only he and his sister survived, and to lose his father and want to join the army? That was an early flirtation with suicide. That was the beginning of his cruelty.

In his The Rebel, Albert Camus demonstrates how tyrants kill others because they won’t kill themselves. He saw deaths in spades too early and may have wondered why he did not die when his mother was losing several of his siblings. But just like he survived all of that death scare, he survived coups and even a coup against him.

Many are angry that the donations to set up a library was obscene. Bigwigs donated the fat of the land to evil, and he once called himself the evil genius. No problem, so long as the library is set up to include all the evils of his brutal reign, the death, the air of funeral parlor, the rhetoric of augury, the state of fear that characterised his army with a state rather than a state with an army, a la Bismarck. Those who have nostalgia for military rule can learn. Just like the Nazi Museum in Berlin, with all the madcap personalities and incidents.

Culled from The Nation