By Emmanuel Oladesu

Nigeria has a lot to learn from Ghana. In the last two decades, the country has savoured credible, transparent and democratic elections that have rekindled citizens’ faith in civil rule.

No political process is perfect, but some enduring democratic features, if emulated, could consolidate popular rule. That has been the experience of the 68-year-old independent country.

Of course, Ghana also has many things to learn from Nigeria. Under the corrective Tinubu administration, Nigeria is taking bold socio-economic reforms that would yield enormous dividends across the sectors for the citizens.

Unlike in Nigeria, the key political actors in Ghana have invested confidence in the electoral process and its capacity to throw out and throw up leaders. This underscores a level of democratic maturity. The implication is that the institution is developing and waxing stronger, and the virile political culture is stable with minimal tension.

Ghanaians have learnt to restrict the battle for presidential power to the ballot box, instead of filing frivolous petitions at tribunals or courts against rivals after the polls, despite the substantial compliance with the Electoral Act, the constitution and due process. Those who lost elections in Ghana have not resorted to vulgarity and uncouth language, unlike in Nigeria where sore losers become vindictive and pedestrian.

The masses, who constitute the majority of voters, are conscious of their obligations to themselves and the country. Thus, if a ruling party misbehaves, its misdemeanour is not overlooked. It would face a severe penalty on polling day. There is no remedy. The opposition takes its place.

Sixty-six-year-old John Mahama, who bounced back during the week as Ghanaian leader, had seen the ups and downs of politics in his country. He has passed through the process that threw him up, rejected him, and reaccepted him.

As vice president, he succeeded the lawyer and scholar, Prof. Atta Mills, who died in office. After spending the residue of the tenure, he contested for the highest office and won. But, he was rejected four years later because he failed to meet public expectations.

After failing at the poll, he never rocked the boat. He accepted defeat, returned to the drawing board, strategised, and kept hope alive. Eight years later, he threw his hat into the ring and defeated former President Nana Akufo-Addo’s anointed candidate, Mahamudu Bawumia of the New Patriotic Party (NPP).

It is interesting that the candidate of the ruling party also accepted defeat. He put the nation first instead of dragging his people into a crisis or invading social media with miscreants to discredit or pull down the process.

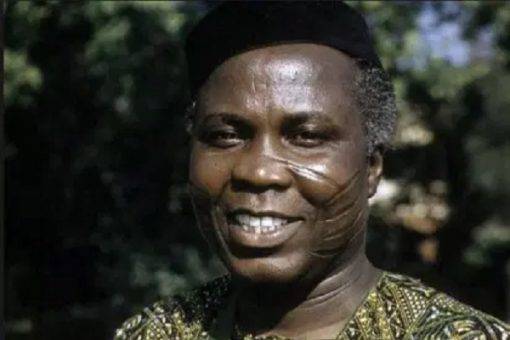

The Ghanaian President was barely two years old when the late Dr. Kwame Nkrumah governed with a latent ambition to make his country a model in Africa. A nationalist and an ideologue, Nkrumah felt he could make progress under a one-party system. He set Ghana on the path of steady progress. However, the first Ghanaian President was not sensitive to the overly ambitious and murderous soldiers of the time. When Nigeria’s Prime Minister Abubakar Tafawa Balewa was violently toppled and killed on January 15, 1966, Nkrumah lampooned the Nigerian incident. A month later, the same tragedy befell him while he was outside the country.

Like Nigeria, the military started to toss Ghanaians around. There were harvests of coups and counter-coups among top military officers – Joseph Ankrah, Akwasi Afriffa, Ignatius Kutu Acheampong, and Jerry Rawlings – leading to intermittent displacements of civilian rulers, like Kofi Busia and Hilla Liman. The country started enjoying stability from Rawlings through John Kufuor to Mills, Mahama and Nana Akufo-Addo.

Yet, during that period, Ghana continued to play a leading role in the African Union, formerly the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), and in mediation and conflict resolutions in Nigeria. During the civil war, General Ankrah hosted the Nigerian Head of State, Gen. Yakubu Gowon, and the Biafran warlord, Col. Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, for a peace conference.

But Ghana ran into economic turbulence from the late 1970s to the late ’80s and many able-bodied youths – professionals and other experts – fled the country. Many stormed Nigeria to eke out a living. They were industrious and never violated the rules of descent where they sojourned. It was ironic. In the 1950s and 1960s, many Nigerians who had relocated to the Gold Coast came back with fortunes, skills and opportunities.

But Ghana soon lapsed into decay, mainly created by political adventurism. As the topsy-turvy reared its ugly head, Jerry Rawlings led a blind and bloody revolution, sweeping away past leaders who allegedly contributed to the economic and political adversity. Rawlings and his Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) first ruled for 112 days and arranged the execution by firing squad of eight military officers, including Generals Kotei, Joy Amedume, Roger Felli, and Utuka, and the three former heads of state – Acheampong, Akuffo, and Afrifa.

Opinion is divided on the violent approach. Many leaders across the world condemned the execution. Ghana, it must be noted, took off from that clean break from the past.

As from 2000, Ghana started rebuilding. It tried to embrace international best practices in re-setting its critical sectors. The country attempted to curb corruption. It also fought an infrastructure battle with a measure of success. Security of life and property became a priority. Its education sector became a reference point to the extent that many Nigerian parents started sending their children to schools in Ghana, and, above all, the sanctity of the ballot box was restored.

On account of these, some investors tried to turn attention to Ghana; a few relocated to the country. Although the size of the Ghanaian economy could not surpass the potentials of what Lagos State had, Ghana, a country of four main regions and other settlements, appeared more serious to teach Nigeria a few lessons. It was because Ghanaian leaders attempted to build, rebuild and strengthen their institutions, particularly those of democracy. Instructively, when he visited Ghana, former United Stpates President Barack Obama, who never visited Nigeria, urged Ghana to sustain the tempo. He fired salvos at Nigeria, which he dismissed as a country of graft.

With the situation today, Mahama could be said to be returning to an unfinished business in a country that is full of hope. He is returning to power and to a big responsibility. There is a need for him to build synergy with the parliament, whose cooperation he will need to drive his reforms. The legislature and the executive should cooperate and achieve more for the country but must be guided by the principle of separation of powers and the accompanying checks and balances.

The country has not been insulated from the hard times. Incomes are shrinking. Towards the end of last year, inflation in Ghana rose to 23.0 per cent.

In the past, the country suffered from military coups, political instability and jihadist insurgencies. Now, an economic crisis is staring the people in the face. The number of the jobless is soaring in geometric proportion. The nation thirsts for economic and constitutional remedies.

Expectedly, Mahama, having dissected the challenges, has also proposed solutions to guide his policies and programmes in the next four years. The four critical areas of his administration are economic restoration and stabilisation, improvement of the business and investment environment, governance and constitutional reviews, as well as accountability and war against corruption. It means that the critical infrastructure for guaranteeing the ease of doing business should be in place. These include stable electricity, a modern road network, investment-driven policies, equitable justice, and the absence of political tension.

The Ghanaian leader is not inheriting a dilapidated economy, despite the long-lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the peculiar cost-of-living crisis, the resort to bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the sovereign debt default.

Being an experienced president in whom much trust and confidence have been reinvested, Mahama would be under pressure to deliver on his campaign promises. The onus is on him to restore trust in government.

Africa, with its vast arable land, should not be hit by food shortages or inflation. The neglect of agriculture is proving costly to the continent. Africa needs to have a deliberate programme designed to boost agriculture. Food security should be prioritised in the overall consideration for a comprehensive national security programme. Mahama should bear these imperatives in mind.

Nigeria and Ghana have cordial relations which predated the pre-colonial days. It should be sustained. Ghanaian and Nigerian leaders should defend democracy in Africa and continue to insist that coups are old-fashioned and military regimes are outdated.

In the days of colonialism, Nigeria and Ghana were a pair in the struggle for independence. Successive leaders of the two countries have maintained cordiality. It was, therefore, sad that a few years ago, many law-abiding Nigerians resident in Ghana became victims of inexplicable, subtle, persistent and violent xenophobic maltreatment.

In particular, Mahama has personal ties in Nigeria. He has been hosted by four towns – Offa, where he is a chief; Ilorin, where he has delivered a convocation lecture; Ado-, where he has fans in the government and among other Ekiti notables; and Lagos, where he is perceived as a friend of Bourdilion, the power house and indomitable centre of influence.

The Ghanaian President is endowed with interpersonal skills. He is affable and his attitudes generate unconditional positive regard to many statesmen on the African continent and beyond, as evident in the attendance at his inauguration as the country’s 12th president. The diplomatic friendliness could be rewarding in boosting cordial relations

Many Nigerians wish him success, hoping he would not allow any crack in his administration. Besides, Nigerians pray for him not to have a gulf between his people’s expectations and the realities that lurk in the corners of inevitabilities in the next four years.

Culled from The Nation