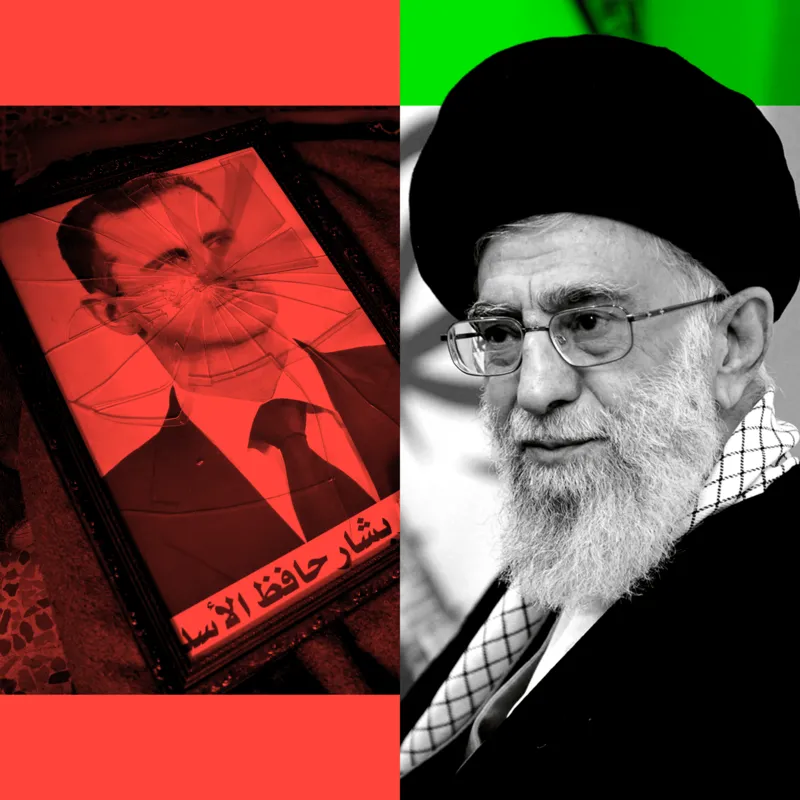

Amid the shattered glass and trampled flags, posters of Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei lie ripped on the floor of the Iranian embassy in Damascus. There are torn pictures too of the former leader of Lebanon’s Hezbollah movement, Hassan Nasrallah, who was killed in an Israeli air strike in Beirut in September.

Outside, the ornate turquoise tiles on the embassy’s façade are intact, but the defaced giant image of Iran’s vastly influential former military Revolutionary Guards commander Qasem Soleimani – killed on the orders of Donald Trump during his first presidency – is a further reminder of the series of blows Iran has faced, culminating on Sunday in the fall of a key ally, Syrian president Bashar al-Assad.

So, as the Islamic Republic licks its wounds, and prepares for a new Donald Trump presidency, will it decide on a more hardline approach – or will it renew negotiations with the West? And just how stable is the regime?

In his first speech after the toppling of Assad, Khamenei was putting a brave face on a strategic defeat. Now 85 years old, he faces the looming challenge of succession, having been in power and the ultimate authority in Iran since 1989.

“Iran is strong and powerful – and will become even stronger,” he claimed.

He insisted that the Iran-led alliance in the Middle East, which includes Hamas, Hezbollah, Yemen’s Houthis and Iraqi Shia militias – the “scope of resistance” against Israel – would only strengthen too.

“The more pressure you exert, the stronger the resistance becomes. The more crimes you commit, the more determined it becomes. The more you fight against it, the more it expands,” he said.

But the regional aftershocks of the Hamas massacres in Israel on 7 October 2023 – which were applauded, if not supported, by Iran – have left the regime reeling.

Israel’s retaliation against its enemies has created a new landscape in the Middle East, with Iran very much on the back foot.

“All the dominoes have been falling,” says James Jeffrey, a former US diplomat and deputy national security advisor, who now works at the non-partisan Wilson Center think-tank.

“The Iranian Axis of Resistance has been smashed by Israel, and now blown up by events in Syria. Iran is left with no real proxy in the region other than the Houthis in Yemen.”

Iran does still back powerful militias in neighbouring Iraq. But according to Mr Jeffrey: “This is a totally unprecedented collapse of a regional hegemon.”

The last public sighting of Assad was in a meeting with the Iranian Foreign Minister, on 1 December, when he vowed to “crush” the rebels advancing on the Syrian capital. The Kremlin has said he is now in Russia after fleeing the country.

Iran’s ambassador to Syria, Hossein Akbari, described Assad as the “front end of the Axis of Resistance”. Yet, when the end came for Bashar al-Assad, a weakened Iran – shocked by the sudden collapse of his forces – was unable and unwilling to fight for him.

In a matter of days, the only other state in the “Axis of Resistance” – its lynchpin – had gone.

How Iran built its network

Iran had spent decades building its network of militias to maintain influence in the region, as well as deterrence against Israeli attack. This dates back to the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

In the war with Iraq that followed, Bashar al-Assad’s father, Hafez, supported Iran.

The alliance between the Shia clerics in Iran and the Assads (who are from the minority Alawite sect, an offshoot of Shia Islam) helped cement Iran’s powerbase in a predominantly Sunni Middle East.

Syria was also a crucial supply route for Iran to its ally in Lebanon, Hezbollah, and other regional armed groups.

Iran had come to Assad’s aid before. When he appeared vulnerable after a popular uprising in 2011 had morphed into a civil war, Tehran provided fighters, fuel and weapons. More than 2,000 Iranian soldiers and generals were killed there while ostensibly serving as “military advisers”.

“We know that Iran spent $30bn to $50bn [£23.5bn to £39bn] in Syria [since around 2011],” says Dr Sanam Vakil, director of the Middle East and North Africa programme at think tank Chatham House.

Now the pipeline through which Iran might have tried, in the future, to resupply Hezbollah in Lebanon – and from there, potentially, others – has been cut.

“The Axis of Resistance was an opportunistic network designed to provide Iran with strategic depth and protect Iran from direct strike and attack,” Dr Vakil argues. “This has clearly failed as a strategy.”

Iran’s calculation of what to do next will be affected not just by the demise of Assad but also by the fact that its own military came off far worse than Israel in the first ever direct confrontations between the two countries earlier this year.

Most of the ballistic missiles that Iran launched at Israel in October were intercepted, although some caused damage to several airbases. Israeli strikes caused serious damage to Iran’s air defences and missile production capabilities. “The missile threat has proven to be a paper tiger,” says Mr Jeffrey.

The assassination in Tehran of the former Hamas leader, Ismail Haniyeh, in July was also a profound embarrassment for Iran.

The country’s future direction

The chief priority of the Islamic Republic from here on in is its own survival. “It will be looking to reposition itself, reinforce what’s left of the Axis of Resistance and re-invest in regional ties in order to survive the pressure that Trump is likely to bear,” says Dr Vakil.

Dennis Horak spent three years in Iran as Canadian charge d’affaires. “It’s a pretty resilient regime with tremendous levers of power, and a lot more they could unleash,” he says.

It still possesses serious firepower, he argues, which could be used against Gulf Arab countries in the event of a confrontation with Israel. He cautions against any view of Iran as a paper tiger.

It has however, been profoundly weakened internationally – with an unpredictable Donald Trump about to assume the presidency in the US, and Israel having demonstrated its ability to pick off its enemies.

“Iran will certainly be re-evaluating its defence doctrine which was primarily reliant on the Axis of Resistance,” says Dr Vakil.

“It will also be considering its nuclear programme and trying to decide if greater investment in that is necessary to provide the regime with greater security.”

Nuclear potential

Iran insists that its nuclear programme is entirely peaceful. But it has advanced considerably since Donald Trump abandoned a carefully-negotiated deal struck in 2015, which limited its nuclear activities in return for the lifting of some economic sanctions.

Under the agreement, Iran was permitted to enrich uranium up to a purity of 3.67%. Low-enriched uranium can be used to produce fuel for commercial nuclear power plants. The UN’s nuclear watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency, says Iran is now significantly increasing the rate at which it can produce uranium enriched to 60%.

Iran has said it is doing this in retaliation for the sanctions that Trump reinstated and which remained in place as the Biden administration tried and failed to revive the deal.

Weapons-grade uranium, which is needed for a nuclear bomb, is 90% enriched or more.

The IAEA head, Rafael Grossi, has suggested what Iran is doing may be a response to the country’s regional setbacks.

“It’s a really concerning picture,” says Darya Dolzikova, expert on nuclear proliferation at the Royal United Services Institute think tank. “The nuclear programme is in a completely different place to where it was in 2015.”

It has been estimated that Iran could now enrich enough uranium for a weapon within about a week, if it decided to, though it would also need to construct a warhead and mount a delivery system, which experts say would take months or possibly as long as a year.

“We don’t know how close they are to a deliverable nuclear weapon. But Iran has gained a lot of knowledge that will be really hard to roll back,” adds Ms Dolzikova.

Western countries are alarmed.

“It’s clear that Trump will try to re-impose his ‘maximum pressure’ strategy on Iran,” says Dr Raz Zimmt, senior researcher at the Israeli Institute for National Security Studies and Tel Aviv University.

“But I think he’ll also try to engage Iran in renewed negotiations trying to convince Iran to roll back its nuclear capabilities.”

Despite Israel prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s stated desire for regime change, Dr Zimmt believes the country will bide its time, waiting to see what Donald Trump does and how Iran responds.

Iran is unlikely to want to provoke a full-scale confrontation.

“I think Donald Trump – as a businessman – will try to engage Iran and make a deal,” says Nasser Hadian, professor of political science at Tehran University.

“If that doesn’t happen, he’ll go for maximum pressure in order to bring it to the table.”

He believes a deal is more likely than conflict, but he adds: “There is a possibility that, if he goes for maximum pressure, things go wrong and we get a war that neither side wants.”

‘Widespread simmering fury’

The Islamic Republic faces a host of domestic challenges too, as it prepares for the succession of the Supreme Leader.

“Khamenei goes to bed worrying about his legacy and transition and is looking to leave Iran in a stable place,” according to Dr Vakil.

The regime was badly shaken by the 2022 nationwide protests that followed the death of a young woman, Mahsa Jina Amini, who had been accused of not wearing the hijab properly.

The uprising challenged the legitimacy of the clerical establishment and was crushed with brutal force.

There is still widespread, simmering fury at a regime that has poured resources into conflicts abroad while many Iranians face unemployment and struggle with high inflation.

And Iran’s younger generation, in particular, is increasingly estranged from the Islamic Revolution, with many chafing at the social restrictions imposed by the regime. Every day, women still defy the regime, risking arrest by going out without their hair covered.

However, that’s not to say that there will be a collapse of the regime similar to that in Syria, say Iran watchers.

“I don’t think the Iranian people are going to rise up again because Iran has lost its empire, which was very unpopular anyway,” says Mr Jeffrey.

Mr Horak believes its tolerance of dissent will be lowered still further as it tries to shore up its internal security. A long-planned new law that strengthens punishments for women who do not wear the hijab is due to come in imminently. But he doesn’t believe the regime is currently at risk.

“Millions of Iranians don’t support it, but millions still do,” he says. “I don’t think it’s in danger of toppling anytime soon.”

But as it navigates anger at home, the loss of its lynchpin in Syria – after so many other blows to its regional clout – has made the job of Iran’s rulers a lot more tricky.

BBC