By Palladium

There are a number of disquieting issues with President Bola Tinubu‘s four controversial tax reform bills transmitted to the National Assembly last September.

Firstly, of course, are a few of the provisions in the bills, particularly the Value Added Tax component of one of the bills, which some governors believe will disadvantage their states. Secondly, rightly or wrongly, is the belief that the bills are polarising, pitting region against region, and one tier of government against another. Mercifully, so far, the bills have not acquired any sectarian hue, except someone along the line wants to force one upon them. Thirdly, and very disturbing, is the fact that few governors, not to say the National Economic Council (NEC) as a body, have bothered to study and digest the bills before either commenting on them or taking inflexible positions.

Fourthly, the pro and con forces have dug their heels in and spoken apocalyptically about their readiness to countenance mayhem on account of the bills. Yet, in all this, it is perverse that the dismissive conclusions reached by many commentators have concerned just one or two provisions in one of the four bills.

The four observations listed above point in only one direction: that Nigeria is not a perfect or even working or workable union, and that the country’s political and business elites lack both the wisdom and the willingness to make the union work. This is why they frame their arguments, discourses, and observations as zero sum-games; why they approach every disagreement or misgiving with a sense of entitlement; and why they assume that in the Nigerian democracy anchored on unsustainable and eclectic constitution bequeathed by the military, electoral blackmail is fair game against an intransigent president. About two months after the bills were transmitted, and the conclave of northern governors announced their diametric opposition to the bills perhaps after taking their cues from NEC, some political leaders (governors and lawmakers) have made insignificant attempt to explicate the bills, preferring instead to whip up public emotions. Till now, no governor or political leader has tried to disentangle the bills one from another, or to zero in on the offending provisions, or suggesting amendments or even general reworking.

When NEC and some political leaders asked for the withdrawal of the bills, it is unlikely they were aware their call indicated their miscomprehension of the role of the legislature, the input lawmakers should have in the working of bills, and the inurement, if not ignorance, of the elite to the dangers constituted by the regionalisation of the bills. The reason bills are transmitted to the legislature is to allow for their reworking, rephrasing, amidst more consultations and expert contributions. It would have been helpful if consensuses had been built before the bills were transmitted, but it is not compulsory that they should reach the legislature unfettered by public doubts and misgivings. The legislature, like the judiciary, is a vital part of the workings of a presidential system, and an indispensable tool to the stabilisation and survival of democracy. It is unclear why NEC and some political leaders discountenanced this process. The 10th Assembly may display some fragility, if not sometimes supine acquiescence, in the face of the blandishments and pressures of the Tinubu administration, a point exemplified by the indecent haste to pass the National Anthem replacement bill, but the tax bills as well as many other bills were unlikely to witness the same frightful haste, especially considering how strongly some states feel about the tax reforms.

Indeed, considered critically, the tax bills are not as deeply polarising as many critics or supporters wish.

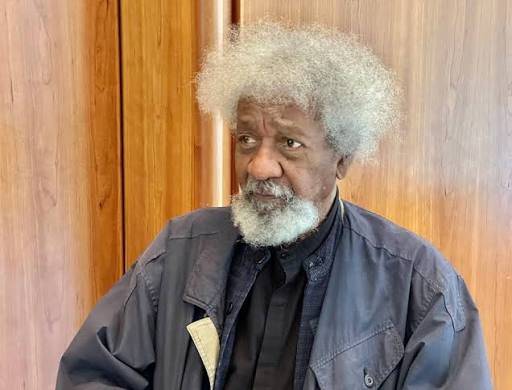

The objects of discord are mercifully few, and the bills overall are revolutionary and desperately needed to help retune the country’s revenue streams, restore order to a chaotic system, give succor to the poor, and unleash states’ economic potentials. When Channels TV recently assembled a panel of six experts to dissect the bills, it was remarkable that while they admitted that some fine-tuning could still be done, they were nevertheless unanimous that the reforms contemplated were urgently needed as a great shot in the arm for the Nigerian economy. Channels TV is no fan of President Tinubu, for while it has tried to be objective, it has hardly succeeded in disguising its oppositional predilection.

The bills may give the impression of being polarising, but they have received nearly unanimously enthusiastic support from the country’s economic experts, and notable and knowledgeable analysts from all regions and across ethnic and religious groups. No bills in recent memory have received such profound support, regardless of the skewed and fairly shortsighted interpretations of the VAT component of the bills.

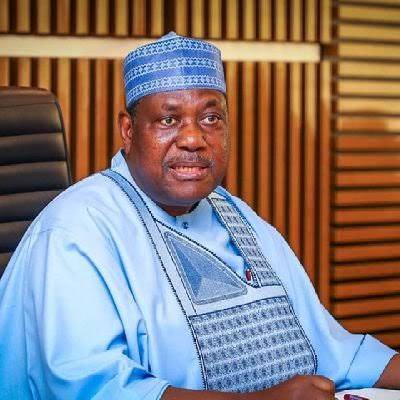

In the past two weeks or so, Borno State Governor Babagana Umara Zulum has unapologetically personified the debate on, if not the opposition to, the bills. His argument is straightforward and a little puzzling. He did not speak to the four bills, as expected, but singled out the VAT issue. According to him, predicating VAT proceeds distribution on derivation instead of on production as provided in the old formula would favour Lagos and Rivers States, and disadvantage many states, including Borno, which he said would be unable to pay salaries. But proponents of the bills have shown by data and projections that his conclusions were far-fetched, and that Lagos would in fact be disadvantaged. Why it did not occur to Professor Zulum that publicly admitting Borno’s insolvency was both humiliating and retrogressive. Even if the governor can substantiate his misgivings, by using Borno’s financial condition to illustrate the unfairness he alleges against the bill, and by framing his arguments so inelegantly he indicates his reluctance to see the problem holistically or project into the future. He could have made the same point by different and dignified logic.

In the heat of the moment, and at a time when a Borno senator, Ali Ndume, acknowledged that he had not read the bills and didn’t care to, it was disappointing that Prof Zulum indirectly abjured his progressive credentials. Controversial issues like the tax reform bills tend to expose the lack of rigour and ideology of many Nigerian political leaders. The National Economic Council was remiss in giving the president the right advice, and so, too, was the Borno governor. They have the resources to hire experts from across the country to help them analyse or deconstruct salient national issues. That they narrowed their search is surprising.

The problem is not that they took issue with the bills, since they have the right to nurse doubts and interrogate facts; the problem is that they seemed strangely unable to analyse the bills without resorting or appealing to regional and electoral emotions.

There are suggestions that had President Tinubu consulted more widely, the bills would have come out less controversial and more acceptable. It is not known exactly just how much consultation the administration undertook, but the tax reform panel admitted that they engaged in very wide consultations across the country.

No one has controverted their claim except the Nasarawa State governor, Abdullahi Sule, who insisted that whatever consultations the panel undertook with respect to the governors was superficial and informal, particularly for such a consequential bill. He may be right. But there is no doubt that consultations were undertaken, and though the bills indicated stupendous quality of legislative drafting, they do not preclude further tweaking. Whether ‘enough’ consultations were done or not, the idea of a legislative process is to enable further consultations. Governors and political leaders should take advantage of the process. Threatening to throw out the bills or insinuating rejection of the president for a second term is unhelpful and amateurish. Both threats sadly indicate that the country is still fraying at the edges, while, even more significantly, it is clear that Nigeria is still not a union, perfect, imperfect or work-in-progress.

It is perhaps time, too, that President Tinubu must learn the art of lobbying beyond just transmitting a great bill or proposing an excellent idea to achieve a more perfect union or a great economy. The country’s six geopolitical zones are unlikely now or in the near future to see the country from the same lens. Indeed, it is not every state in one zone that sees national or even regional issues from the same prism. Beyond the noise, even Prof Zulum does not have the wide support he thinks he has on the tax bills among the North’s intelligentsia. There may be protests here and there, but many critical northern thinkers see the tax reform issue beyond short-term disadvantages, preferring instead to focus on the immense potentials to reset the northern economy and make a clean break from the retrogression, feudalism, and irresponsible dependency that have undermined the region and bred decades of complacency and chaos. President Tinubu is presiding over a presidential system; he has a responsibility to invite key lawmakers for breakfast, lunch or dinner in order to lobby them, explicate the issues at hand, get them to see the future beyond today, and gradually extricate them from the stifling economic and cultural anomalies of the present. He may have the brightest ideas and the best bills, and he may even be as good-natured as anyone can be, but he must learn to reach out, drive a great and hard bargain, and ensure finally that politics is played transcendentally above, ethnicity, region and religion. Tweaked here and there, the tax reform bills will probably be passed; but while the president is encouraged to ignore the electoral threats regarding 2027, he should see what has happened as a lesson to come out of his shell and engage more meaningfully and aggressively with his constituency, the lawmakers.

Culled from The Nation