By Segun Ayobolu

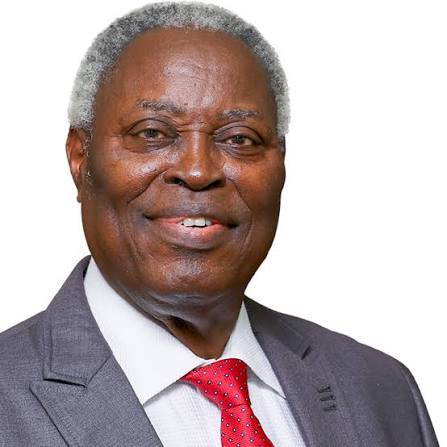

Because of the long years, he has put into public service, first as Executive Secretary of the Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFUND) and now as Chairman of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) since 2015, it is so easy to forget that Professor Mahmood Yakubu’s first calling is as an academic and that he is a first-class historian by specialization. The INEC Chairman returned to his forte this week when he was one of the speakers at an international conference organized by Arewa House, the reputable northern think tank, in collaboration with the Faculty of Law, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, on the 110th anniversary of the amalgamation of Nigeria in 1914.

According to this newspaper’s reportage of the event, “Eminent Professor of history, Mahmood Yakubu, has said Nigeria will not disintegrate, despite its challenges. Yakubu told those who regarded the amalgamation of the Northern and Southern protectorates in 1914 as an artificial contraption that would eventually snap to bury the thought. He said it is not a miracle that Nigeria has remained indivisible 110 years after its amalgamation but by the determination of the diverse people to manage their heterogeneity. Yakubu dismissed calls for divisions among Nigeria’s diverse ethnic nationalities, saying the country has maintained deep-rooted historical ties that have existed among various communities long before the amalgamation”.

As Yakubu pointedly put it further, “I have made peace with the fact that I am Nigerian. If some people think Nigeria is artificial, they should know that nations are created in different ways and are consolidated over time. Tell me one nation that was put together by consensus. The fact that we are here for over a century is a plus for Nigeria”. Contrary to Professor Yakubu’s postulation, there are many who would contend that there is indeed something of the miraculous in Nigeria’s continued survival and cohesion, no matter how fragile her unity, for over a century plus years after the amalgamation.

For example, the country outlived a three-year fratricidal civil war(1967-1970) that cost over two million lives. Most remarkably, a prominent member of the Igbo ethnic group that had sought secession, Dr Alex Ekwueme, had risen to become Vice President of Nigeria a little more than a decade after the end of the war in 1970. But for the military intervention that terminated the Second Republic in 1983, the unfolding dynamics of the democratic process could very well have seen Ekwueme succeeding President Shehu Shagari in 1987 on the platform of the defunct National Party of Nigeria (NPN). But that is in the realm of conjecture.

Again, the country survived the protracted struggle against the annulment of the June 12, 1993, presidential election won by the late Chief MKO Abiola and the perpetuation of military dictatorship; a struggle that often pushed the polity to the edges of implosion. Out of the tortured womb of that crisis, has rather emerged the current democratic dispensation that has remained unbroken for over two and a half decades. Indeed, so intense has the ever-deepening economic crisis particularly of the last two decades been that it is a sheer wonder that the depth of the existential trauma has not fractured Nigeria’s febrile and complex fault lines beyond repair. The country’s repeated amazing capacity to rescue victory from the jaws of defeat and disintegration and pull back from the brink of seemingly inevitable disaster has led many to believe that there is some sort of divine purpose and design to the evolution, creation, and sustenance of Nigeria as an entity.

There are indeed those who would read into Professor Yakubu’s logic the often peddled but now largely discarded mantra that ‘Nigeria’s unity is indivisible and non-negotiable’. That was a phraseology that derived from the civil war and its coercive ‘Go On With One Nigeria’ motivation as well as the dictatorial psychology of military domination. I however believe that this is not the spirit in which Yakubu made his submission. According to the news report on his contribution at the conference, “The INEC Chairman noted that the people’s relationships and interactions predated British colonization and the amalgamation of what is now called Nigeria. According to him, these historical ties have only grown stronger and will continue to do so”.

For him, the continued cohesion of Nigeria after a century and ten years of amalgamation is a desirable aspiration to be continuously and consensually nurtured and worked for, not a non-negotiable idea to be rammed down the throats of the component parts of the country. This is why both democracy and federalism must be continually deepened and strengthened as the indispensable imperatives for a united Nigeria predicated on voluntary association and not ultimately unsustainable compulsion. By all indices, the political, economic, cultural, geo-strategic, and psychological benefits and advantages of a united, democratic, and federal Nigeria far outweigh the uncertain outcomes and unpredictable consequences of a disintegrated polity.

Some of those who oppose the continuity of Nigeria and contend that there is absolutely nothing ‘non-negotiable’ about any polity point to such collapsed federations as the defunct USSR, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, or Sudan among others. But why should we make failed state-building experiments and not successful ones are our models of reference? Why not learn appropriate lessons from the factors responsible for the collapse of failed states so as not to experience the same avoidable sad fates in our own efforts at nation-building?

There are those who still refer to Chief Awolowo’s famous description of Nigeria as ‘an artificial entity’ made up of diverse ethnic nationalities and thus not a nation in the true sense of the word to argue the case for the non-sustainability of Nigeria’s unity. The Sardauna, Sir Ahmadu Bello is also said to have observed, obviously at a moment of ill-tempered politics, that ‘the mistake of 1914’ had come to light following certain constitutional disagreements between the North and the South. But such statements cannot be justifiable bases for arguing for the viability or otherwise of the Nigerian state.

As far back as 1973, for instance, the eminent political scientist, Professor Billy Dudley, had interrogated the accuracy of the claim of Nigeria’s artificiality. In his words, “In some respects, the boundaries of most of the African states are arbitrary; few of these states have a ‘common bond’ holding their people together, at least in the sense required either by Lord Hailey or Chief Awolowo. Nevertheless, it is only partially true and certainly not sufficient to warrant the charge of their being ‘artificial’. Dudley argued that in the precolonial era, there had been the creation of linkages among the various peoples that make up the area to be known as Nigeria through communication nets, trade, and the transmission of ideas before the imposition of imperial rule “thus making the notion of ‘Nigeria’ as a creation of the British so extremely misleading”.

In his inaugural lecture evocatively titled ‘What Man has Joined Together’, delivered at the University of Ibadan in 2019, renowned political scientist and Director General of the Nigerian Institute of International Affairs (NIIA), Professor Eghosa Osaghae, avers that Awolowo was right in arguing that Nigeria was not a nation in the sense that the Scots and Welsh, for instance, were in terms of a common culture, language and sense of belonging. However, according to him, “But that could not have been because Nigeria is a mere geographical expression. No state or nation is a natural construct. All states and nations are literally geographical expressions, but expressions given form, content, and character by the process of nation building”. In any case, are the Yoruba, Edo, Tiv, Igbo, Hausa-Fulani, and other components of Nigeria necessarily less artificial than Nigeria? Osaghae explores these and other issues relevant to our ongoing quest for a viable Nigerian entity 64 years after independence from colonial rule.