By Olatunji Dare

If you don’t find “columnism” in the dictionary, you have my word that I did not make it up.

I first encountered the term in an essay for The New York Times by the lexicographer, William Safire. Following him, I have used it in this space to denote the art and craft of writing a newspaper or magazine column.

But I did so with not a little wariness. In the war of attrition between the Babangida regime and the progressive section of the news media, I feared that the inventive managers of its duplicitous political transition programme might replace the second letter in “columnist” with the first letter of the English alphabet, in the process transmuting the term to “calumnist” and damning practitioners the noble art of columnism to wear a term of reproach through the life of the regime and beyond.

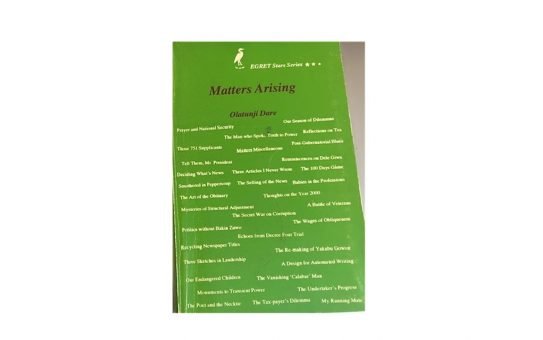

Columnism has been my preoccupation, on and off, but more on than off, for some 30 years. But as I hinted last week, it is time to go. This is the final installment of “At Home Abroad.” the brand name of the column since this newspaper debuted some 14 years ago. In its previous iteration on different platforms, the column ran as “Matters Arising” and furnished the title of a selection from my collected journalism between 1985 and 1993.

Writing the column has been a great honour and privilege.

At a time like this, one is expected to reflect on one’s adventures in the business and share with fellow practitioners in general and the younger ones in particular nuggets of the best practices one has learned over the decades.

It is incomparable, this privilege of inflicting one’s views and biases, and prejudices on others week after week on the issues of the day, issues large and small, with no direction other than the broad editorial policy of the journal, the enduring examples of some of the finest practitioners of the craft dead or living, the laws of defamation, the dictates of decency, the moral law within you, and the values that have shaped you.

It is in fact more than a privilege: it is a trust that must be earned and constantly re-earned.

The trust carries with it a corollary duty: to deploy your gifts, skills, insights and judgment to help shape the standards of sense and sensibility; and to produce a picture of reality on which sound public policy can be founded. The columnist must not get so absorbed in the privileges and trappings that he or she loses sight of this overarching goal.

The most accomplished columnist, working under the tyranny of deadlines, with unfolding situations and incomplete or faulty data, can be permitted his or her mistakes. But it is inexcusable for the columnist to be irresponsibly wrong, or to persist in error after a truer picture of the situation has been provided. The columnist is thus obliged to refresh his or her knowledge, update the available information, cultivate a multiplicity of sources, eschew oracular pronouncements, and instead, cultivate humility.

The political columnist is concerned with power, its use and abuse. To write about it in a manner that commands respect and trust, he or she must be in a position to observe power closely, to go beyond appearances, or what one of the greatest practitioners of the craft, Walter Lippmann, called “the foam of events.”

To write competently and confidently about the use and abuse of power from a distance, you have to be stationed up close. But not so close that you cannot see clearly. You have to maintain an “air space” between you and the authorities. Watch out for the seductions of power that come in many guises and disguises, and never put your trust fully and uncritically in princes and principalities.

You can be harsh, even brutal, if that is what the situation demands. But never write from malice or hatred, for they undermine that charity that is the foundation of the good society.

That is what I have distilled from the reflections and reminiscences of some of the best exemplars of the craft. I have tried to apply them to my work. How well I have succeeded is for the reader to judge, but I can say that they have served me well, just as they have served the sources from which I derived them and will doubtless serve those who diligently seek to apply them.

Retiring the column is not the same thing as retiring from journalism. On retiring from the University of Ibadan, the eminent historian, Professor Jacob Festus Ade-Ajayi noted that he was only retiring from the teaching of history at an academic institution, not retiring from history. Like the great man, I should make clear that I am retiring from columnism, not from journalism.

From time to time I will, as a contribution to the national policy dialogue, write on issues that move me or amuse me or faze me or irritate me, but not under the AT HOME ABROAD rubric. The frequency will be determined by circumstances. I count it an honour that this newspaper has accorded me that privilege.

In my writings over the decades, I have won many friends and admirers. Many of them remember and remind me of things I wrote long ago and now remember only dimly, and they do so largely from appreciation. I thank each and every one of them. I know I did not always live up to their expectations, yet they kept faith with the column week after week.

The column has also attracted its fair share of critics and antagonists. When the paper still provided facilities for instant comments without mediation, the column was the haunt of one anonymous troller who could never bring himself to see or say anything good in it – or in the columnist for that matter. Within minutes of the column being posted, he is there excoriating him remorselessly and imputing the basest motives to him.

The last time we heard from him, he accused me of cowardice and dishonesty for not naming a public figure whose diverting convocation address in one of the universities I had shared with readers. When someone in the attentive audience pointed out that the public officer in question was named in the article, this unrelenting antagonist rejoined that it was my fault that I had not followed the elementary canons of newswriting — who, what, where, when, etc.

With antagonists like that, you can never win. I wonder what became of him when The NATION shut down the instant-response ap on its website. He had one thing going for him, though: he was knowledgeable, and his prose was admirable.

Together, admirers and antagonists kept me on my toes much of the time. I often had to reckon with or anticipate what the latter would say.

My written evaluations of submissions by my students, I realized years later in a different setting, must have gnawed at their self-esteem, especially in my early years as a university teacher. It is not enough to say that I meant no harm. It is a measure of their large heartedness that they rank among my best admirers today. They all constituted a crucial part of my education. I learned from them even as I sought to teach them.

It remains to thank the proprietors, managers, editors, staffers and operatives of The Nation Newspaper for the courtesies and kindnesses they showered on me from the day I first set foot on their premises.

For now, au revoir.