When Credit Suisse opened its first office in Saudi Arabia in early 2021, Bruno Daher, the cigar-smoking head of Credit Suisse’s Middle East business, declared it a “key growth market”.

The branch, at the intersection of King Abdullah and King Fahd Road in central Riyadh, was symbolic of the deepening relationship between the storied Swiss lender and the wealthy Kingdom.

Yet two years later, the relationship has soured spectacularly.

A Saudi investor played a key role in the demise of the 167-year-old Swiss lender after tin-eared comments sparked a run on the bank’s shares.

In the process, the Saudis have blown up their own investment, sparking recriminations at home and raising serious questions about the country’s ability to gain a foothold in the global banking industry.

Credit Suisse has had a presence in Saudi Arabia since 2005 but ties have deepened in recent years as Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman (MBS) opened up the notoriously conservative kingdom to foreign companies and influence.

The Swiss bank won a local banking licence in 2019, allowing the lender to offer a full array of products and services as it sought a share of the oil-rich nation’s lucrative deposits.

When veteran investment banker Michael Klein was sent out by Credit Suisse in search of investors to fund a radical restructuring plan last year, he turned to his contacts in the Middle East.

To the delight of the board in Zurich, the former Citibank executive returned with a $1.5bn (£1.2bn) cheque signed by Ammar Al Khudairy, chairman of the Saudi National Bank (SNB).

SNB is the Kingdom’s largest bank, with more than $250bn in assets. It was formed in 2021 following a tie-up between the country’s National Commercial Bank and Saudi Samba Financial Group. Today it dominates the kingdom’s lending market with a 30pc market share.

The bank already held majority stakes in lenders in Turkey and Pakistan. However, Al Khudairy, an engineering graduate from George Washington University in the US, saw Klein’s approach as an opportunity for SNB to propel itself on to the international stage.

In October, Al Khudairy told the Wall Street Journal: “The Saudi market is the 700-pound gorilla economically in the region, and just getting [Credit Suisse] to engage with us in Saudi Arabia would be more than good enough.”

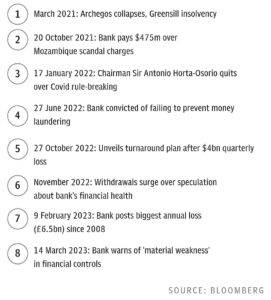

Despite his financial advisers raising concerns about the investment, following a litany of recent scandals at Credit Suisse, MBS directed the government-backed SNB to inject $1.5bn into the beleaguered Swiss lender last November.

For years, Swiss banks have acted as a haven for wealthy Saudi families. The crown prince wanted the investment to act as a flashy first foray for the kingdom into the global banking industry.

The investment made SNB the bank’s largest shareholder, with a stake of nearly 10pc.

At the time, Al Khudairy said: “We looked at the downside, we believe it is limited.” He hailed it as a “manifestation of the new Saudi Arabia” as the country sought to diversify its economy away from oil.

He has lived to regret those words. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) last month sparked fears of contagion in the banking sector, with fears centering on Credit Suisse. The bank had already seen shares slide over 70pc after a series of scandals and missteps.

Al Khudairy was asked on the sidelines of a conference in Riyadh whether SNB would consider injecting more capital into Credit Suisse. “Absolutely not,” he said.

Those two words precipitated the demise of one of Switzerland’s oldest banks, as well as Al Khudairy’s own career.

One senior investment banker says: “Had the Saudi bank head not said what he had said, I can’t see the Credit Suisse saga playing out as it did.

“All he had to say was: ‘We have not received a request for support from Credit Suisse. But if one comes we will consider it on its merits at the time.’ But he didn’t, and the rest is history.”

The comments triggered a sell-off in Credit Suisse’s shares and ultimately prompted the Swiss government to intervene. A rescue by UBS was hastily arranged over a weekend, an arrangement Swiss officials said was necessarily to prevent a broader financial crisis.

SNB and MBS were left red-faced and furious by the cut-price deal. Al Khudairy was last week ousted after losing $1.2bn on the investment in four short months. Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund and the Saudi-based Olayan family also took sizeable hits from the forced tie-up.

Beyond SNB, the debacle has raised questions about the future relationship between Saudi’s wealthy residents and Swiss banks.

Following its takeover by UBS, Swiss regulators controversially wiped out some of Credit Suisse’s bondholders, while returning capital to equity holders.

AT1s, which are a bank’s riskiest bonds, were introduced in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis to ensure losses would be borne by investors, rather than taxpayers. They represent a key $275bn market for the funding of European banks.

Typically in a write-down scenario, shareholders are the first to take a hit before AT1 bonds face losses.

However, Swiss authorities inverted this hierarchy, letting shareholders get pennies on the dollar while AT1 holders got nothing.

Experts speculate that the decision was taken to appease the Saudis and stop them pulling business from other Swiss lenders.

The boss of a London-listed bank says: “I’m absolutely convinced it was politically motivated.”

He adds that, beyond keeping the Saudis on side, officials also likely wanted to give something back to longstanding domestic investors who had backed Credit Suisse for generations.

“My guess is that they felt the need to give some money back to the equity holders and it will be those at the lower end of the register, all the Swiss people who owned part of Credit Suisse because it’s been around forever,” he says.

However, the returns handed to shareholders pale in comparison to the market value of their holdings even in the days before Credit Suisse’s emergency rescue.

At SNB, chief executive Saeed Mohammed Al Ghamdi has now replaced Al Khudairy as chairman.

Mohammed Ali Yasin, chief strategy officer at Al Dhabi Capital, said Al Khudairy “was a victim of giving his honest opinion at such a tense time for Credit Suisse”.

He adds: “In hindsight, seeing the buyout rate of Credit Suisse by UBS, his answer was the right course of action: waiting for the crisis to be clearer.”

Shabbir Malik, an analyst at EFG Hermes, believes SNB is now unlikely to pursue its dreams of establishing itself as a global player in investment banking.

“[The Credit Suisse investment] worried certain investors mainly because SNB invested overseas at a time when the domestic opportunity is more compelling,” he said.

Al Ghamdi’s chief task for the moment will be simply to repair SNB’s reputation, while MBS will be assessing how the bank made such a costly blunder.

Meanwhile, UBS is embarking on a major cost-cutting drive as it integrates its former biggest rival.

As for Al Khudairy, he is unlikely to reemerge on the front lines of Saudi finance anytime soon.

In an attempt at gallows humour, the chief executive of the London-listed bank says: “I don’t know what happens when you lose your job at a large Saudi bank. Do you think he’s buried in the desert? I have this whole image that it hasn’t ended well. We’ll never see him again.”

The Telegraph