In the careful architecture of modern governance, public procurement is not merely a technical process. It is an economic lever, a social equaliser, and, when properly calibrated, a powerful engine of national inclusion.

This reality framed a landmark peer-to-peer learning session hosted by Nigeria’s Bureau of Public Procurement (BPP), in collaboration with the International Trade Centre (ITC), UN Women, and the Public Procurement Service (PPS) of the Republic of Korea. The session, which was held virtually on 11 February 2026, brought Nigerian procurement officials face to face with one of the world’s most advanced affirmative procurement systems, offering both inspiration and a detailed, data-driven roadmap for reform.

At stake was the transformation of Nigeria’s procurement system into a deliberate instrument for economic inclusion. The focus was the forthcoming National Policy on Affirmative Procurement (NPAP), an ambitious framework designed to ensure that the immense spending power of government becomes a vehicle for empowering women, youth, persons with disabilities (PWDs), veterans, and other historically excluded groups.

In essence, the session signalled Nigeria’s intent to align procurement practice with national development priorities, ensuring that public expenditure catalyses opportunity, broadens participation, and strengthens economic resilience.

● A Vision for inclusion: Nigeria’s National Policy on Affirmative Procurement (NPAP)

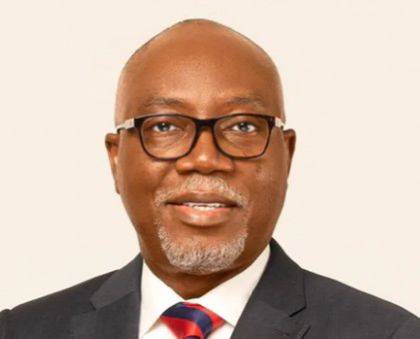

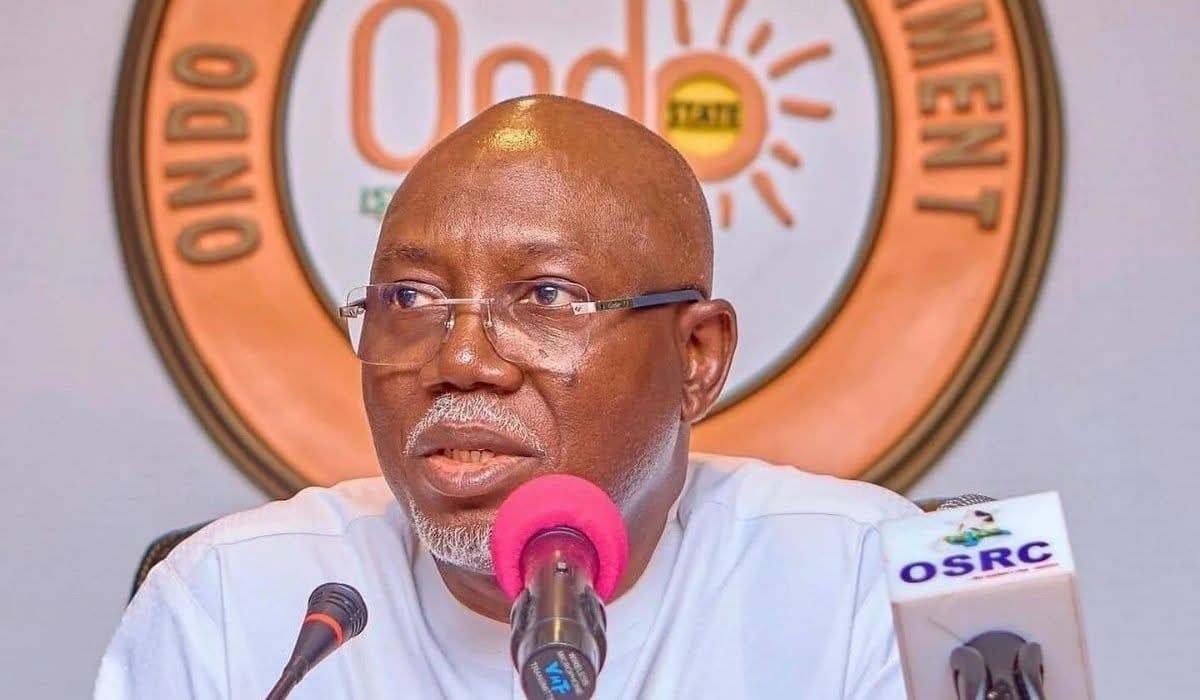

The intellectual anchor of the session was the keynote presentation by Dr. Adebowale Adedokun, Director General of the Bureau of Public Procurement. His paper, “Operationalising the Upcoming National Policy on Affirmative Procurement,” was delivered on his behalf by Engr. Eugenia Ojeah, BPP’s Focus Person on the National Technical Committee on the NPAP. It laid out a comprehensive vision for embedding inclusive procurement across Nigeria’s public sector.

At its core, the NPAP recognises a fundamental paradox. Public procurement accounts for an estimated 10 to 25 per cent of national Gross Domestic Products [GDP] and represents more than half of total government expenditure, yet the participation of priority groups remains below one per cent. This imbalance is not merely statistical; it reflects structural barriers that have long excluded capable entrepreneurs.

As stated in Dr Adedokun’s presentation, the policy therefore seeks “to leverage public procurement to promote social inclusion, reduce inequality and feminized poverty, enable equitable/inclusive participation in Government contracts by the target groups.”

To avoid any ambivalence, the priority groups are clearly defined: women-owned and women-led businesses (with a 51% ownership threshold); youth-owned enterprises (for citizens aged 18-35); businesses owned by PWDs; and enterprises led by veterans, the elderly, and internally displaced persons. These groups possess talent and entrepreneurial drive but face systemic obstacles such as limited access to finance, restricted professional networks, and discrimination.

To be clear, the policy’s mechanisms are designed to be both practical and transformative:

● Reservation of Opportunities: A minimum percentage of contracts will be reserved exclusively for target groups, creating guaranteed entry points into public contracting.

● Preferential Scoring: Bid evaluation processes will include additional scoring margins that recognise the developmental value of inclusive participation.

● Mandatory Subcontracting: Large contractors will be required to subcontract portions of their work to qualified businesses within target groups, expanding participation throughout supply chains.

● Joint Bidding Consortia: SMEs will be encouraged to form consortia, enabling them to pool capacity and compete for larger contracts.

● Data-Driven Monitoring: Dedicated data capture systems will establish baseline metrics, allowing government to track progress and ensure accountability.

Beyond these technical provisions lies a deeper economic logic. Inclusive procurement stimulates job creation, strengthens business sustainability, promotes diversity, and reduces poverty. It also addresses broader social challenges, including youth unemployment and economic marginalisation. In this sense, procurement becomes not merely an administrative process but a stabilising force within the national economy. The BPP will coordinate closely with all MDAs, state governments, development partners, and financial institutions to ensure that inclusive procurement becomes embedded within everyday governance.

■ Lessons from South Korea’s global benchmark

If Nigeria’s policy represents a bold vision, South Korea’s experience offers proof that such transformation is achievable on a national scale. The session’s technical highlight was a detailed presentation by Mr. Bongki Shin, Deputy Director for International Cooperation at the Korea PPS and manager of the Korea ON-line E-Procurement System (KONEPS). His presentation deconstructed the sophisticated architecture of Korea’s affirmative procurement framework.

South Korea’s model demonstrates how technology, policy clarity, and institutional commitment can converge to create an inclusive and highly efficient procurement ecosystem. At the centre of this system is KONEPS, a fully integrated national digital procurement platform that serves as a single gateway for all public tenders. It is worth noting that Nigeria’s equivalent, NOCOPO, is operational and continually being enhanced.

Meanwhile, KONEPS connects over 72,000 public organisations with approximately 600,000 suppliers, handling an annual procurement volume of roughly USD 110 billion. The platform ensures transparency, eliminates information asymmetry, and provides specialised digital marketplaces.

These “dedicated shopping malls” are a cornerstone of Korea’s inclusivity strategy. They provide distinct, easily navigable digital spaces for:

● Women-Owned Enterprises: Products from certified women-owned businesses are automatically flagged with a special mark, and a mandatory quota requires public agencies to purchase at least 5% of goods/services and 3% of construction works from them annually.

● Start-ups (“Venture Mall”): A specialised mall dedicated to products from young, innovative companies.

● Social Enterprises and PWDs: Dedicated malls feature products made by people with severe disabilities and other social enterprises, ensuring they have a visible and accessible marketplace.

Korea’s framework also tackles the two biggest hurdles for SMEs: cash flow and capacity. Through the “Network Loan” programme, SMEs can secure loans for up to 80% of a contract’s value from partner banks, using the PPS contract as sole collateral. This is complemented by the “Procurement Sherpa” service, a one-stop consulting programme that provides expert guidance to novice suppliers on navigating the entire procurement process. Furthermore, the system guarantees prompt payment, with suppliers often paid on the same day they invoice.

Equally important is the Subcontractor Protection System. This digitally monitors the entire subcontracting chain, ensuring that payments for materials and labour are sent directly to protected commitment accounts. This prevents larger contractors from withholding payments, thereby protecting smaller, more vulnerable firms from exploitation. In 2023 alone, this system safeguarded approximately USD 45.4 billion in payments to over 83,000 subcontractors.

Mr. Shin’s presentation made it clear: Korea’s system proves that inclusive procurement, far from undermining efficiency, strengthens competition, improves supplier diversity, and enhances overall system performance by building a healthier, more resilient SME sector.

■ Building an inclusive procurement future for Nigeria

The peer learning session concluded with a clear and actionable pathway for Nigeria’s reform journey. The immediate priorities are the finalisation and gazetting of the NPAP, followed by nationwide sensitisation efforts to ensure both procuring entities and target businesses understand its provisions. Capacity-building programmes will equip procurement officials to implement the policy effectively, while targeted training will prepare priority groups to compete successfully. Digital monitoring systems will be crucial for tracking compliance and measuring real-world impact.

The significance of this initiative cannot be overstated. Public procurement is one of government’s most powerful economic instruments, and Nigeria’s embrace of affirmative procurement signals a paradigm shift in how government spending is understood. It is no longer merely a mechanism for acquiring goods and services; it is becoming a deliberate instrument for nation-building.

By drawing on global best practice from Korea, while tailoring solutions to its own realities, Nigeria is laying the foundation for a procurement system that reflects both efficiency and equity. The journey ahead will require discipline and sustained political will. Yet, with a clear policy, a robust action plan, and strong international partnerships, a procurement system that works for all Nigerians is fast becoming an institutional reality.

In conclusion, it is not out of place to note that in the careful architecture of modern governance, inclusive procurement is not an ornament but a foundation, and Nigeria has begun to lay it with purpose.

■ Sufuyan Ojeifo is a journalist, publisher of THE CONCLAVE, and communications consultant.