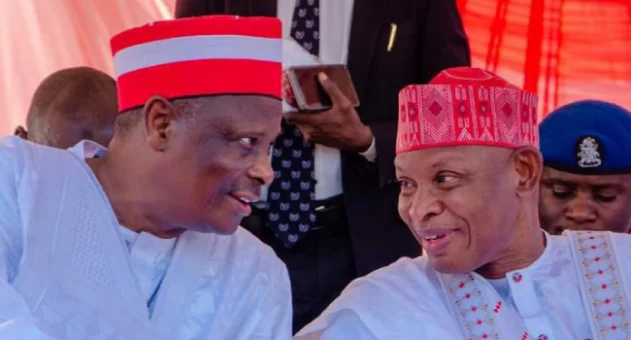

With all the drama he could muster, an embittered Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso recently declared January 23, 2026, the day his erstwhile protégé, Kano State Governor, Abba Yusuf, did the unthinkable by resigning from the New Nigerian Peoples Party (NNPP) to join the All Progressives Congress (APC), ‘World Day of Betrayal!’

Not many could have predicted that such a day would come given the close ties between the two men. Yusuf started out as the one-time Kano governor’s Personal Assistant. Kwankwaso would go on to appoint him Commissioner of the important Ministry of Works.

Such was the bond of loyalty between them that back in 2014, Yusuf who was then an APC member gladly relinquished his senatorial ticket for his mentor to go to the National Assembly and remain politically relevant. A man who was capable of such selflessness now suddenly finds himself being profiled as treacherous.

But the connections weren’t just official or political, they were also familial. Like many, I had in the past recycled the incorrect information about Yusuf being married to Kwankwaso’s daughter. This isn’t true. The incumbent governor has two wives and one of them is from his erstwhile godfather’s extended family – but is not his biological daughter.

Perhaps what makes the parting so galling for some is Yusuf’s choice of new friends – many of them his former boss’ associates now turned bitter foes. He spent much of the last two years in a vicious war of words with his predecessor, Abdullahi Ganduje. In fact, one of his first acts in office as governor was the demolition of structures and monuments worth billions of naira built by the former administration.

On Monday, the fellow he so bitterly reviled was the one raising his hands in endorsement before a cheering throng at the Kano Government House when Yusuf formally registered as APC member. Such is politics; no permanent friend or foe, only permanent interests.

Over the last two years, close associates of the governor had been nudging him to break free from the suffocating control of his long time boss and ‘be his own man.’ He definitely reached the point where he found such calls irresistible.

Despite the best efforts to portray the fracture in the Kwankwasiyya family as the ultimate betrayal, such splits are not unheard of in Kano politics. This is a state where power is rarely transferred without a fight. From the First Republic till date, politics here has been shaped by recurring battles between godfathers and godsons they helped to office.

Time and again, powerful patrons have anointed successors, only to turn into their bitterest enemies once those successors acquired power, autonomy, and their own following.

Yusuf broke with Kwankwaso but before him Ganduje also went down the same path as he tried to prise himself from the controlling grip of his former boss. Kwankwaso having handed power to Ganduje in 2015, was confident that loyalty would endure. Instead, his successor asserted independence with ruthless efficiency. What followed was an all-out political war that polarised Kano and split families, communities, and institutions.

By the time the dust settled, Ganduje had not only defeated his godfather politically but had also redefined the state’s power structure. Yet the irony is unmistakable: he soon began to play the godfather role, exerting influence over party structures and political appointments, only to face resistance from emerging forces and shifting alliances.

This pattern is neither accidental nor new. It is rooted in Kano’s long tradition of mass politics, its highly mobilised electorate, and influence of its larger-than-life personalities who see power not merely as public trust but as personal property.

The story started in the First Republic with the rivalry between Mallam Aminu Kano and his former allies. He was not a godfather in the crude, transactional sense common today, but an ideological mobiliser who built a mass movement around the talakawa. Yet even then, Kano politics showed early signs of what would later become a defining feature: intense internal schisms that sooner than later ripped apart any pretence to loyalty.

By the Second Republic, the godfather–godson template had become clearer. Then Governor Abubakar Rimi split from Aminu Kano in 1981 due to ideological, generational, and strategy disagreements within the People’s Redemption Party (PRP). The younger, more eloquent and charismatic man, leading the radical “Santsi” faction, clashed with Kano’s “Tabo” wing over his technocratic cabinet.

Rimi’s attempt to diminish the influence of Emir of Kano, Ado Bayero, by creating four new emirates in 1981, caused a severe rift with Kano, who felt the actions were disrespectful to tradition.

That radical step mirrored what Ganduje did in the twilight of his governorship when he tried to cut Emir Sanusi Lamido Sanusi to size by creating four new emirates.

Kwankwaso, himself, emerged as governor under the banner of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), helped by an alliance of heavyweights in the state. Once in office, he moved swiftly to dismantle the influence of those who helped him rise. What followed was a bruising intra-elite war that reshaped Kano politics for years.

He would later become the textbook godfather he once rebelled against under his Kwankwasiyya movement. But like most godfather projects, it eventually ran into the same familiar problem: succession.

What makes Kano different from many other states is not the existence of godfathers – they exist everywhere in Nigeria – but the consistency and intensity of godson rebellion. In this state, godsons rarely remain subordinate for long. Once they taste power and build grassroots legitimacy, they push back.

Kano’s voters, unlike those in many other states, have repeatedly shown a willingness to punish perceived political arrogance – whether from godfathers or godsons. When Rimi’s differences with Aminu Kano became irreconcilable, he resigned as governor and defected to the then Nigerian People’s Party (NPP) to contest the 1983 election. He was handily beaten by the PRP candidate, Alhaji Sabo Barkin Zuwo.

With the politics of the state in such a flux at the moment, it’s hard to say who the voters will back following the intriguing realignment of forces that has taken place. What is evident is that Yusuf has gutted his erstwhile NNPP home, taking with him a huge chunk of the structure from top to bottom.

What is being created is potentially quite formidable given that he’s joining forces with a largely united APC machine that had strengthen itself over the last one year with defectors from across the political spectrum in the state.

For his part, Kwankwaso faces a painful rebuilding process with many of his most influential and resourceful foot soldiers now in the rival camp. His options are painfully limited given that he would be going to any table of negotiations with a very weak hand.

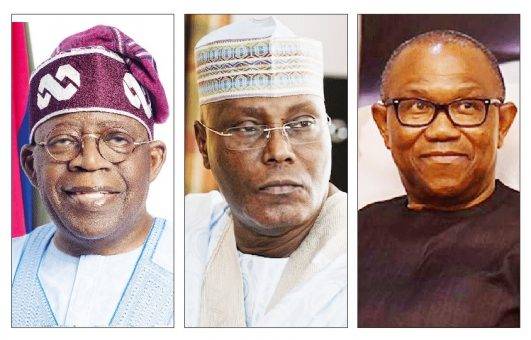

He cannot really turn to the African Democratic Congress (ADC) which is looking more and more by the day like the Atiku Democratic Congress. Even the much speculated link up with Peter Obi in an as-yet-to-be identified platform looks more like a fairy tale that may never become reality.

In 2023, with his machine intact and motivated, Kwankwaso and his NNPP pulled a massive 953,179 votes at the presidential election. Then candidate Bola Tinubu and APC came second with 513,846; Atiku Abubakar and PDP managed 118,445 votes, while Obi’s Labour Party only garnered a measly 30,089 votes.

It’s hard to see how with barely 12 months to the next general elections, the wounded former governor is able muster anywhere near one million votes in Kano either for himself or for any other ticket he may decide to support. What is clear is that the 2027 election in the state, driven by either voter anger or indifference, may well produce a lopsided outcome in favour of one side as fallout of recent developments.

Culled from The Nation