History often likes its villains, sometimes more than its heroes. Heroes titillate but can make you yawn. Virtue stirs the soul. Vice pushes us over the cliff. So, Villains make us gasp for exploits of the unknown. In John Milton’s Paradise Lost, Satan tempts with tempests in contrast to Christ’s even temper.

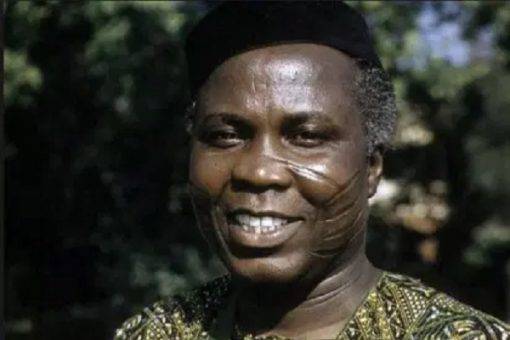

In the Southwest, a familiar villain is Samuel Ladoke Akintola. He was a premier, a polyglot, a wordsmith, a thinker, a wit, a maoeuvrer and a political thespian. If he had all these before he departed history, he would still be a boring, if an eminently accomplished, man. But his imprint on time is what many of his Yoruba folks highlight: his epic betrayal.

There have been efforts in the past few decades to nuance his tale, to pose him as a man of principle and an icon of governance, and even a faithful follower of the great Yoruba avatar: Chief Obafemi Awolowo.

This season marks 60 years since he was dispatched during the 1966 coup. Some thought he met his comeuppance while inking their displeasure at the reason behind the episode when a certain Captain Okoro led some soldiers to his Agodi Residence.

But a question remains quiet in the tale. Why did Akintola not surrender? His deputy, Chief Fani-Kayode, was not killed. They grabbed him, and Akintola was aware. After initial gunfire exchanges, the soldiers ordered him to drop his gun. But the premier would not. He battled to the death.

This act may benefit from historical insight from a book largely ignored. Aristocratic Rebel is a biography of Nigeria’s top spy in the 1960’s and later an inspector general of police, M.D. Yusufu.

The book is written by Ayo Opadokun, former secretary of NADECO.

The book was presented with Yusufu in attendance in 2006, which means he endorsed all that Opadokun wrote in that underplayed classic of the Nigerian story.

According to Yusufu, Akintola had been invited over to Kaduna by the then premier of Northern Region, Sir Ahmadu Bello on the eve of the coup. What was the reason? According to Yusufu, the NPC with then governor Kashim Ibrahim had asked the Sardauna to convey the decision of the Northern People’s Congress (NPC).

“It is very clear that the Yoruba don’t like Akintola. Please, call Akintola and tell him that this alliance is off. Let him go and sort out his problem with the Yorubas.” That was the message the Sardauna conveyed to S.L.A.

“I was the most senior Federal officer, so I had to receive Chief Akintola at the airport. The Sardauna sent along with me one of his ministers – Abuto Obekpa. That is why the New Nigerian (newspaper) photograph on the day of the coup captured me receiving Akintola at the Kaduna airport,” said Yusufu.

According to Opadokun, …”if Major Kaduna Nzeogwu and his fellow plotters had lingered past that week before staging their coup, perhaps the course of Nigerian history would have altered.” History does not follow a script. It happens based on a constellation of forces. Hence, all true historians know that nothing is inevitable. It does not follow a dice. Hence, we cannot say the coup was inevitable.

When Akintola returned to Ibadan, what might have boiled over in his mind? We shall never know. But it was obvious from the meeting with his coalition partners, he was a lonely man. Could he have gone back to his Yoruba folks? Could he have bended a knee to Awo and his people? Could he have apologized for his alliance with the NCNC against Awo, for his role in the wetie and the conflagration in the West? For his attitude to Ogunde and the songs of the minstrel that made him a pariah of the region? As professor Jide Akin Osuntokun has reminded us, he was disappointed with appointments at the centre with the Tafawa Balewa government. He was beginning to see that his quest for justice was now belly up. He was already seeing the fruits of treachery. He was not only isolated by his federal allies but also the Yoruba street where some had corrupted his initials S.L.A to Ese ole, that is the leg of a thief.

Did he welcome the coup as denouement? Was his act of defiance to the soldiers actually a bravado of surrender to fate. Was it an escape route for his pride? Was the Are Onakakanfo playing out the last act of a Yoruba eschatology?

This is not only a material of historical inquiry but also for a sort of psyco-history. Did death save him from disgrace? For the realist, this is a grist to investigate the last chapter of valour, a man who had been a fellow traveler of Awolowo and his Action Group, and was such a loyal deputy that he was a natural to take over from Awo as the premier of the region.

He was a great administrator who actualized much of Awo’s dreams, from Cocoa House to the now Obafemi Awolowo University. Yet, as Shakespeare wrote, the “spirit of men is in their blood.” Akintola saw power and imbued its hubris. The artist, novelist and playwright might see the conflict between character and ambition unfold in a brilliant soul. The playwright may tempt the premise that the man saw death as an opportunity and his great escape from a public apology or opprobrium. That is what a Gibbons or Tacitus or, Ibn Battuta or any classic historian may dig up from an Akintola narrative.

But there is another angle, for the traditionalist or cultural historian. One, it is the belief that the Are Onakakanfo, the post of the Yoruba generalissimo, is fated to tragedy. Afonja set the blood-strewn stage. By taking that position, he had signed a cultural death warrant. Did he contemplate it that night of bullets?

The other point was farther back when the young men of the Yoruba race went to Ife to swear an oath to accept Awolowo as the leader of the Yoruba. The deal foreordained the AG. The other part of the oath is not this essay’s remit. But Akintola was part of the young men. And a line in that oath is, eni to ba dale abale lo. He who betrays will die.

Eminent lawyer Rotimi Williams also swore. When he turned his back on Awo, he did not oppose him. It is said that his mother warned him against defying the oath. The man turned to his profession and was never a politician again till he died.

Was S.L.A’s fate tied to his breaking an oath, or it is mere superstition? This is the sort of story that excites political scientists and historians. Insights into the past and its big men are not just about what they do but how they are framed by the societies they made and made them.

In Sophocles’ King Oedipus, the Greek playwright teases the audience as to whether the story of Oedipus’ end is a matter of prophecy or hubris, or both. Our own Ola Rotimi has no patience in his adaptation, he thunders “the Gods are not to Blame.”

He is taking the realist tack while the play nurtures doubt and sometimes endorses the agenda of the mystical.

In his essay about such artistic quandary, Soyinka writes of Achebe’s Arrow of God and the author’s contempt for cultural mystery.

The Nobel laureate describes it as “the secularisation of the profoundly mystical.” Shakespeare addresses this ambiguity in his Macbeth, a king who thinks no man born of a woman can kill him. Mystic fuels hubris to death.

But to begin any such dialogue here, historians and biographers must address the riddle: Did S.L.A. commit suicide?

Culled from The Nation