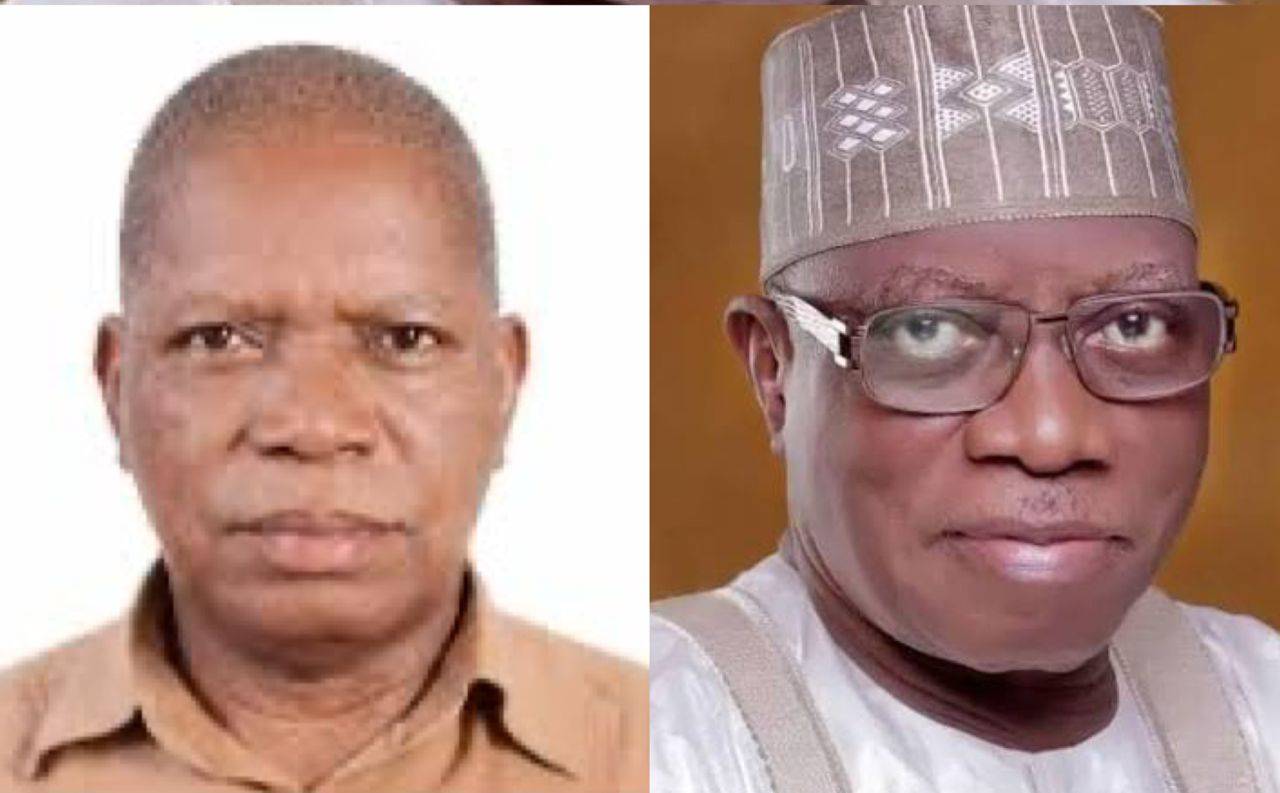

Is the angel of death on a rampage in the journalistic community? Perhaps not. Yet, in the past few months, this morbid ghost has snatched in quick succession, Messrs. Dan Agbese, Yakubu Mohammed and Lewis Obi, three of our best in the profession. In every sense, the three are all-time journalistic greats. None of them could have been anything less than a senior editor in the best newspapers in the world. Journalism will miss them sorely.

The tide of death is one that humanity has to live with. It respects neither status nor gender, neither age nor race. It is a leveller.

Indeed, as the good book says, no one is strong in the day of his or her death. All we can do then is to be prepared to face it whenever it comes. On their part, the bereaved can only relish or regret the memory of the deceased depending on how they lived their lives. What one is writing is, therefore, not a lamentation but a reflection on the dead and how they impacted me and certainly many others, in plying our trade.

Of the three journalism giants, Mohammed and Lewis impacted my career in journalism most. (I had earlier written a tribute to Mr. Agbese). The best newspapers in the world would have been willing to pay whatever the price to have any of the three on their editorial staff. And that not just because of their talents but as importantly also because of their discipline and professional integrity. They were in a class all their own.

My path with Mohammed’s first crossed in 1982 while I was reporting for the Ibadan station of the Nigerian Television Authority (NTA). It was during the mandatory National Youth Service programme, and I was covering politics and, occasionally, the judiciary, at the pleasure of Mr. Biodun Ladekomo, then Manager, News and Current Affairs, at the NTA, Ibadan. Despite the hectic nature of television reporting, I managed to freelance for the _National Concord_ and _Sunday Times_, the two most widely circulated newspapers then. The former ran my articles more regularly, and that encouraged me a great deal. I travelled to Lagos quarterly to pick up my freelancer’s pay. On each occasion, I would stop by to express my gratitude to the editor, a mild-mannered gentleman of slight build from the Igala ethnic stock, in the present day Kogi state. He was always gracious and had nice comments for my articles. During one of such visits, he asked if I would like to work for his newspaper. Then I was still flirting with the idea of making a career in television broadcasting, and so I wasn’t quite sure how to respond to that question. However, as my one-year tour of duty at NTA drew to a close, it was clear to me that Ibadan, despite its relatively low cost of living, did not fascinate me as a city. It lacked the vivacity and the mega-cosmopolitan character and diversity of Lagos. Ibadan was insular in a rather disconcerting way.

The _National Concord_, owned, by the late Chief Moshood Abiola and located in Lagos, was already a trail-blazing daily. Mohammed, its editor, wrote a consequential weekly column, which I found quite interesting on account of the quality of both his thoughts and his lucid prose. He was racy without being shallow. His column covered an assortment of issues of national and global interest. Even before I met him in person, I had become his admirer.

By the end of my service year, I had made up my mind to go into print journalism, persuaded that that was God’s plan for me in that season.

I promptly moved to Lagos, and my first port of call was the _National Concord_ office in Ikeja, halfway between the local and international terminals of the Murtala Muhammed Airport.

When I entered Mohammed’s office that Monday afternoon in 1983, he was reading that week’s edition of _The Economist_ of London. That caught my attention because in my undergraduate days, a professor of journalism had held up the journal as the “best edited newspaper in the world.” And it is arguably so, if only you are ready to endure the paper’s often extremely conservative views and leaning.

Anyway, I told Mr. Mohammed that I was done with the National Youth service and would like to work for his newspaper. He congratulated me and asked me to return the following Thursday for a job interview. When I arrived, he handed me some opinion articles meant for the Op.Ed pages and asked me to edit them for publication. It was a mèlange of the good and bad. Some were well written, in my estimation, and could be published with minimum rework. Others were so badly written that they needed to be rewritten entirely or trashed altogether.

About an hour later, when I was done, he reviewed my work and thereafter called the company’s personnel manager, and directed her to issue my employment letter as the Subeditor to the editorial board headed then by Mr. Ray Ekpu. It was a position that brought me in contact with some of the most influential opinion contributors to the Concord newspapers. Their articles were passed to me for editing and placement on the Op.Ed. pages. I then also was allowed to write every week on the opinion pages for about three years until I was promoted and moved to the *African Concord*_magazine, first as a Senior Staff Writer, and later Assistant Editor and Head of the National Desk in which capacity I supervised such talented reporters like Oluwambo Balogun, Emma Madueme, Babafemi Ojudu, Sam Omatseye, Dele Momodu, Victor Omuabor, etc.

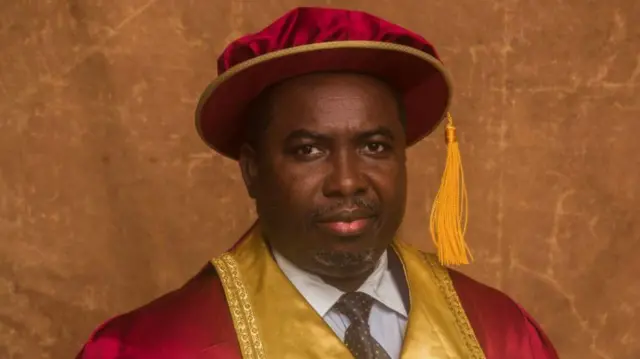

It was at the _African Concord_ that I had my first intimate contact with the legendary Lewis Obi. Like Mohammed, who had by then left the Concord Group to co-found _The Newswatch_, Obi was slight of build, unassuming, and well informed on literally every subject. As editor and later managing director and editor-in-chief of the pan-African magazine, Obi was a perfect example of humble but effective leadership. During our often boisterous weekly editorial meetings, he was always admirably calm. His lamb-like meekness nonetheless concealed a steely self-confidence. He earned everyone’s respect largely because of his intellectual profundity and his dialectical and honest approach to controversial topics. Even if you didn’t agree with him, you could see why his position was the most realistic. He approved travels to anywhere, in and outside the country, for his reporters, as long as they would return with outstanding stories.

During editorial meetings where cover stories were debated and planned, he would let everyone have his say. And whenever he weighed in, his vast experience made all the difference. He was always sober. One word or sentence he would add or take out of a copy made it much better. Put simply, Obi was an editor’s editor. He often reminded his staff that reporting was basically storytelling and that no important detail must be left out. Reporters are to keep their stories uncluttered and simple, not turgid. Readers need not read a story twice to get what you are saying, he would emphasise. His weekly column was indeed a demonstration of what he preached. It was a must-read in many corporate offices because of its relevance to the issues of the moment. His versatility in analysing and simplifying otherwise complex matters endeared him to thousands of readers. Needless to say, he mentored many in the art of editing and column writing.

Mr. Obi was uncommonly wired. I never saw him lose his cool, even in the face of mischievous provocation.

When he was nearly assassinated in front of his Ikeja residence in the late 1980s, it was almost inconceivable to many of us, his staff, that any normal person would want to kill such a harmless fellow. He had closed from work about 8.00pm on the fateful day and was heading home. At the entrance gate of his residence on Toyin Street, Ikeja, a gang of murderers unleashed a fusillade at him as he waited for his gatekeeper to open the gate so he could drive in. It was a trauma that shook his then young family who helplessly watched the tragedy unfold. The incident occurred around 9.00 pm when I had just finished working on the magazine’s cover story for the week. When the sad news reached me, I took off immediately for Mr. Obi’s residence. On getting there, I saw his friend and neighbour, Mr. Tom Borha, a Concord columnist and one-time deputy managing director of the Concord Group. He was horror-struck as his friend Obi, was bleeding profusely from gun wounds.

The first hospital we took him to rejected him. We then got in touch with the surgeon-wife of the late Chief M.C.K Ajuluchukwu, a former General Manager of Concord Newspapers. She said we should drive him right away to the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH), where she worked then as a consultant. As we drove Mr. Obi to the hospital that night, I noticed his determination not to succumb to death despite the fact that he had lost many pints of blood. As soon as we arrived the emergency department of LUTH around 10.30 pm, Dr. Mrs. Ajuluchukwu, who was already waiting for us, swung into action. She said that Mr. Obi had lost much blood and needed rapid blood transfusion. We were there all night, praying and hoping that nothing fatal would happen to this good man who was only in his late 30s. It was months later before he could resume duty, having recovered substantially from the trauma and the injuries.

When Obi fled Nigeria for asylum in the United States to escape the Abacha goons, I knew it was something he resented. He was a die-hard optimist who believed that with the right leadership, Nigeria could be a great nation. That he lived to be 77 was quite the work of grace, for which I am sure he and his family were grateful to God. I can only hope that he was close enough to his Maker at the point of death.

For his family and the family of Mohammed, I pray for the consolation of the Holy Spirit. May they rest from their labours, and may their great legacies be evergreen.

-Venerable Okey Ifionu, a former deputy managing director of THISDAY Newspapers, is now an Anglican priest.