So alarming and concerning did this column perceive President Donald Trump’s recent threat to invade Nigeria militarily to check what he described as ‘Christian genocide’ that, over the last three weeks, we have examined diverse dimensions of this warning and its implications. Our central contention has been that this undisguised threatened violation of Nigeria’s sovereignty constitutes not just a danger to the incumbent administration of President Bola Tinubu but an indictment of Nigeria’s ruling class as a whole. Those members of the political elite, who thus gloat over Trump’s categorisation of Nigeria as a ‘now failed’ State and feel surreptitious vindication by the American leader’s contemptuous disdain for Nigeria, are as much an object of his scorn and ridicule as those in power at the centre today on the platform of the All Progressives Congress (APC).

It is instructive that over the last week in the United States, there have been incidents of fatal attacks on innocent citizens by trigger-happy gunmen, resulting in several deaths. One of such killings took place in the vicinity of the White House, leading to the death of at least one National Guard officer and another being injured. In another instance in California, four school children were said to have died in a mass shooting at a child’s birthday party, with several others suffering from various degrees of injuries. Such tragedies have become routine in America where deaths from senseless mass shootings have become endemic. But such failings do not justify the overgeneralized categorisation of that country as a ‘now failed’ State.

In the same vein, Nigeria’s challenges with insecurity do not necessitate its being depicted in derogatory and pejorative terms. This is particularly so as the accusation of ‘Christian genocide’ in Nigeria completely misses the mark and successive Nigerian governments have not been indifferent or insensitive to the need to tackle the assorted acts of insurgency threatening the country’s territorial integrity and cohesion. It is instructive that various Nigerian groups and individuals in the diaspora actively peddled the propaganda of ‘Christian genocide’ in the country, which President Trump and other far-right Republican ideologues enthusiastically bought into. The harm which disaffected members of the political elite can inflict, directly or indirectly, on their own country reinforces the imperative of forging a viable and enduring elite consensus as a necessary condition for national stability, peace and progress.

Incidentally, America today also suffers from the plague of a lack of elite consensus. The greatest military and economic power on earth today, despite evident signs of a gradual weakening, is described in the media, academia and other platforms of public discourse in that country as a badly divided society torn right through the middle between the liberals and the more conservative Republicans. Indeed, the degree of polarisation in America may be far deeper than the variant of elite fractiousness in Nigeria as is evident in the bitterness of recent electoral contestations in that country with President Trump instigating an insurrection at the Capitol, a symbol of American democracy, protesting his loss in the 2020 presidential election, which he described as a fraud.

However, America has the advantage of strong and resilient institutions capable of safeguarding democratic tenets, principles and values, particularly through Judicial intervention, as is the case during Trump’s ongoing second term, when he has stretched the constitutional limits of Presidential powers to their utmost bounds. So far, various courts at the lower levels have blocked the Trump administration’s policy idiosyncrasies and acts of executive over-reach even though he has generally had his way on appeal at the Supreme Court, where he succeeded in getting a majority of conservative judges appointed during his first term. Yet, this has not prompted anyone to label America as a ‘now failed’ State, nor have aspersions been hurled at judges who understandably base their Judicial decisions on facts before them, interpreted within the context of their worldviews and value-orientation.

But the central point of this piece is the urgent imperative for the political elite in Nigeria to forge the necessary class consensus across political party, ethnic, regional and religious divides without which there cannot be any basis for stability, peace, progress and development. This does not mean that the various factions, factions and tendencies of the Nigerian elite should forget their differences and create an artificial and unnatural commonality. That would be the perfect recipe for a one-party State, which would be detrimental to the continuous nurturing and consolidation of a genuine democratic order, which is a necessary condition for economic development and national cohesion. Rather, forging an elite consensus involves members of the elite recognising their differences and identifying those areas where they must work in unison and accommodate each other, even while vigorously maintaining their differences as regards ideological orientation, policy articulation and philosophical disposition or worldview.

One area of critical importance for cultivating viable elite consensus among the various factions and tendencies that constitute Nigeria’s ruling class is reaching a common agreement on the indispensability of a transparent, credible and efficient electoral process as a cardinal element of an inclusive democratic system. This implies that both elected officials and their ruling parties, as well as those in opposition, develop a common commitment to the sustenance of democracy. Those who lose elections will not clamour for military intervention or external invasion because of their disenchantment with electoral outcomes while those in power will not undermine or render the opposition ineffective. The elite in power and those in opposition are two sides of a coin that are both critical to the sustenance and continuous development of democracy.

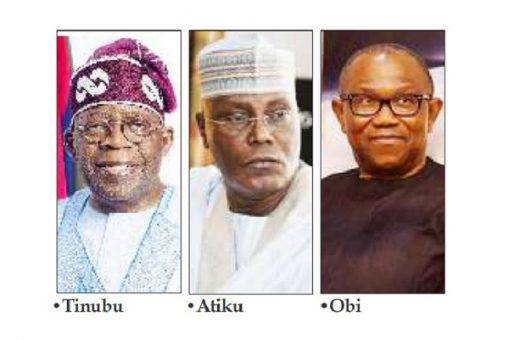

But then, those in opposition cannot expect the party in government to enforce cohesion within their ranks or help them to devise political strategies to strengthen their parties. That is a responsibility they must undertake on their own. Thus, the continued lamentations of leading opposition politicians on the plight of their parties such as the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), Labour Party (LP) and the New Nigerian Peoples Party (NNPP), which they blame on deliberate destabilization by the ruling APC, is unnecessary and unproductive. There is absolutely no basis for former Vice-President, Atiku Abubakar, to have deserted the PDP with his supporters for the emergent All Democratic Congress (ADC), all in a quest for a platform on which to contest the next presidential election. In further bifurcating the PDP, which already has roots in all 774 Local Government Areas across the country as well as the 8,809 Registration Areas/Wards, Atiku has weakened the possibility of a stronger, more viable opposition arising to effectively challenge the APC at the 2027 polls.

The ADC is still largely inchoate and is unlikely to become a political machine capable of effectively challenging for power at the centre come 2027. It will also be recalled that it was Atiku ‘s intransigent refusal to allow the PDP national championship to revert to the South after his emergence as presidential candidate of the party in 2023, in violation of its zoning principle, that provided for rotation of power between the North and the South, created the grounds for the fragmentation of the PDP, its loss in the 2024 election and it’s unfolding catastrophic implosion. Indeed, the concession of the presidential tickets of the defunct Alliance for Democracy (AD) in alliance with the All Nigeria Peoples Party (ANPP) and the PDP to the Southwest in 1999, to compensate the Yoruba for the annulment of the June 12, 1993 presidential election won by Chief MKO Abiola is the kind of elite consensus necessary to stabilize democratic governance to promote economic progress and political stability in Nigeria.

In the case of Mr Peter Obi, he has proven to be utterly clueless in resolving the protracted crisis in which the LP has been immersed. Surprisingly, even his running mate in the 2023 presidential election, Mr Datti-Ahmed, appears to have deserted his erstwhile boss and aligned with a different faction of the LP. Part of the problem is that Obi, just like Atiku, is more interested in finding a platform to actualize his presidential ambition rather than helping to build a solid opposition front irrespective of whether or not he emerges as the presidential candidate. With this kind of individualistic approach by these key opposition leaders, it is unlikely that they can build a formidable front to meaningfully challenge the ruling party for power at the centre in 2027.

Another area where there must be a consensus on the part of Nigeria’s political elite is the need to join hands across partisan divides to fight the deep-seated and long-standing endemic poverty and grossly unjust inequality that are at the root of Nigeria’s current chronic insecurity challenge. This will entail elite unanimity on fighting the industrial -scale corruption that pervades our national life such that humongous funds criminally diverted into private pockets can be made available to boost food production, provide affordable but qualitative healthcare, generate jobs for millions of our youth, improve access to qualitative education and properly as well a equip and motivate our security agencies in the ongoing do-or-die struggle against diverse forms of terror against the Nigerian State.

•This page was first published December 6, 2025

Culled from The Nation