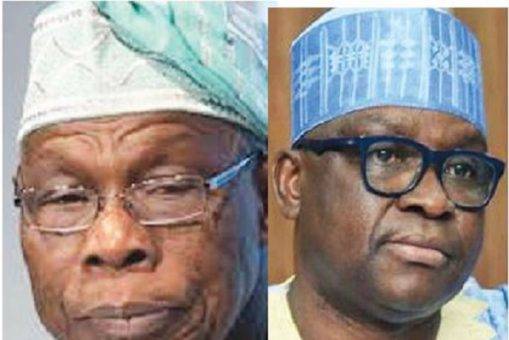

Never in Nigeria’s political history have we witnessed a father-son duo like Olusegun Obasanjo and Ayo Fayose. It makes a fun tale for a festive season, except that this is not, at bottom, a funny story.

If we needed a father-son story for the ages, politics and the southwest could never have chosen a better cast. You can call them a dysfunctional family. You can call them the odd couple. But they belong to each other as against each other.

A quarrel – and a good one – is an important grist for the gist. And if Obasanjo were to pick a son, history gave him a better one than his bloodline could. In this relationship, there is mutual respect because there is mutual contempt. One sentiment cannot divorce the other. Love and scorn never inhabited a better embrace.

This is because they have similar traits. They both crave public theatre. Both covet the subversive streak. They disdain decorum or restraint. Both crack the public rib. Both display an earthy temperament, or what some can call bush men. Remember Fayose’s fake neck-brace and Obj’s tearing of party card?

The one does not respect age, the other does not act his age. Some calls both elders, one being 65 and other allegedly 89. It is mutual fascination. The one could stop by the road side for a bite of roasted corn or plantain. The father could crash a ‘mama put’ for lumps of iyan and swigs of oguro.

The story is told of how Obj, in the heat of the June 12 debacle, was hosting a meeting at his Ota farm. He wanted to down some pounded yam and egusi, and he wanted to eat it the best way to enjoy it: on the ground. No finesse of dining table, tray, chair, table cloth et al. Some arrivals concerned him and he wanted to be sure there was not yet in his compound any person of the Yoruba aristocracy. Once that was clear, his buttocks hit the ground and he dug in, as his wife would describe him, as a bush man.

If Fayose was not tempting the bear, why did he want Obj in his birthday lair? It was not as if they had been chummy. At best, they were both affably distant. Public courtesies are no friendship. In fact, they reinforce animosity.

Did he not get the hint when the man said he would not come free, and why did he send him dollars? Was it to broadcast to the world that he bought Obj’s presence? Maybe that was how Obj saw it, and he exacted a revenge or preempted Fayose’s public swipe at him for accepting his money.

Was it a bribe? Maybe, but not in the legal sense. It is money of deference. But Obj does not see deference. He sees rebellion. As a soldier, he understands what it means to mutiny. He knows plotlines. Was it not the same Obj who summoned Kabiyesis to their feet?

Obj also loves ambush. Fayose did not see that coming. So, when the man mounted the stage, it was as if there was a director behind the scene. Husband and wife stood, dressed in entwined glamour to mark the grandeur of a 65th birthday. Was it the day father and son would hug, and the bitterness of the decade would fade away? The father would serenade son, and they both would laugh away the tempest of the past. After that, a languor of reconciliation. Boring. No one lives boring stories.

Not so fast. Poet Lord Byron wrote, “revenge is sweet, especially to women.” Byron might have known that some men do revenge for career, like Obj. There was a quality of respect for Obj that day from the visage of Fayose and his wife as the elder spewed out profanities on a man’s special day. Omoluabi is the core of being Yoruba. If you don’t have it, your kinship is delegitimised. Obj said he didn’t have it.

Husband and wife, according to Obj, had taken a rebuke in a private phone call. They therefore did not expect a public show. They underestimated the old fox. The man can do anything anytime, and that is why he is obj. if the drama took place in secret and remained there, it meant he was not the Ota man.

Stanley Macebuh, in an interview for the Guardian Newspaper, with Onukaba Adinoyi-Ojo, had described Obj as “crafty, very crafty.” Fayose knew that enough of a man who called himself father and threw him out of government house.

Was it not the same Obj, who showed up General Olutoye? Was it not the same man who did little to win the civil war but took credit for everything, made himself Nigeria’s indispensable warrior, and made sure every other person was a poor soldier. He alone was the good soldier. Was he not the one who would not give Gen. Alani Akinrinade his plaudits, although he was the same fellow who helped negotiate and concluded the war? The same Akinrinade circled the home of S.B Bakare where Obj hid in the firestorm of the Dimka coup. When he became head of state he would not say thank you. He is guilty of what psychologists call the fear of gratitude.

So, it seems Fayose wanted drama on his birthday, and no one could provide a better thespian script than the Ota man, an archenemy as elder, a boor and a bully. Maybe it was what he bargained for and maybe the former Ekiti governor relished a new fight.

Read Also: Akinnadewo urges Christian, Nigerian leaders to deepen humanitarian efforts

After all, he lashed back in a letter to Obj, thanking him for showing that he belonged to a zoo. The other person who used such foul language in public is Nnamdi Kanu. It must have hurt, and so Obj outsped him in making the letter public.

We had a father and son sort of feud before and this was in the east between the great Zik and Chuba Okadigbo.That was a serious one. There was no humour in that encounter. The young Chuba described Zik’s words as “the ranting of an ant.” Zik never forgave him. Rather he poured out a curse. For those who believe, Zik’s curse was effectual on Okadigbo, who rose later to the eminence of a Senate president before he was orchestrated out of office. By who? Obj. The Ota man is the tortoise in every Nigerian tale.

But Obj has not uttered a curse. Many may not take him seriously because they believe he is too much of an old rascal for the gods to hear him.

In his play Tempest, Shakespeare said: “good wombs have born bad sons.” Many fathers have fallen short of their sons. Okadigbo might have thought so of Zik, although there was no intimation of prior father-son tie in them. This essayist confronted Okadigbo a few years after Zik’s curse on him and wondered if it was true he was going to make peace to avert the curse. True to the former senate president, he turned irate and he might have resorted to something fistic if not for the posh milieu of the restaurant in Victoria Island.

The tragic thing about their feud is that neither Fayose nor Obj fought because of some high principle or ideology. It was just street brawl. I might have recommended a great classic, Fathers and Sons, by Russian writer Ivan Turgenev who engaged fathers and sons across generations who were at odds over whether Russia should be liberal or nihilist. That is why the Obj-Fayose duel is not just about an odd couple, it is an odd story.