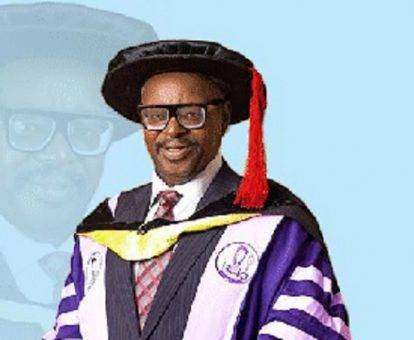

At the commencement of his inaugural lecture titled ‘The Nigerian State: A Country Without Countrymen’, Professor Babatunde Olusegun Agara of the Ambrose Alli University, Ekpoma, Edo State, professed his guiding life credos of faith in God Almighty as a Christian, commitment to positive societal change beneficial to the masses and adherence to the Marxist tenets of revolutionary transformation in the realm of economics. His analysis of the different manifestations of disruptive violence in contemporary Nigeria combines the values, assumptions and outlook of radical political economy a la the late Claude Ake with a rigorous application of the theoretical framework and conceptual classifications of comparative politics and strategic studies.

The most attractive, informative and useful feature of this inaugural lecture is his exhaustive interrogation of the identities, operational modalities, value-orientations and organisational structures, especially of the diverse non-state actors currently threatening the Nigerian state’s monopoly of the instruments and techniques of violence with negative consequences for the country’s territorial integrity, unity and political stability.

He identifies what he describes as ‘the evil triad’ of insecurity, threats of secession and herders’ invasion’ as the prevailing most potent sources of danger to the security of lives and property in Nigeria. Surely, those who have taken up arms against the Nigerian State, snuffing out the lives of fellow citizens with impunity at will, do not see the victims of their violence as fellow countrymen or women. Understanding the nature, characteristics and motivations of the diverse individuals and groups involved in these largely asymmetric acts of violence is thus critical to finding enduring solutions to the protracted violence that has plagued the Nigerian State over the last decade and a half.

This is partly why the content of this lecture should be of particular interest to Nigerian policy makers and those involved in various forms of conflict mitigation, conflict control, conflict containment and conflict management in Nigeria.

Professor Agara’s interrogation of the phenomenon of insurgency encompasses features, manifestations and tendencies that include the entirety of Africa beyond Nigeria. One of the forms of insurgencies which he focuses his searchlight on is that of ‘States against citizens’. He avers that states can mount an insurgency against their citizens, including the enforcement of sanctions against those who violate their laws through extant legal processes or “through the clandestine use of illegal violence designed to intimidate and terrorise citizens with the intention of preventing them from opposing the government and disobeying or contravening the state’s laws”. The latter objective is achieved through psychologically and physically restricting and constricting laws, or more brazenly, the outright elimination of adversaries of incumbent governments in control of states’ apparatuses.

The second kind of insurgency examined in the lecture is that of citizens against citizens. According to him, “A major manifestation of this type of insurgency is by vigilante violence and ethnic or tribal conflicts. Although over 80% of the insurgency experienced in the world today is located within Asia and Africa, its manifestation has always taken the form of ethnic conflict. The vigilante type emerged primarily because of the inability of the police to control crime, and these vigilante groups, at least in Nigeria, later metamorphosed into ethnic militias…this type of ethnic insurgency has been further complicated by religiously motivated violence, thereby making the divide between ethnic conflict and religious violence difficult to delineate”. He attributes the eruption of ethnic insurgency to such factors as group loyalty and identity, feelings of marginalisation and alienation, struggle for access to state power and the quest for resource control.

Professor Agara also examines another form of insurgency, which is the expression of discontent by citizens against the policies of a state or its leadership, leading to “either organised or spontaneous uprising or riots having neither clear political goals nor organised leadership”. This type of insurgency, he points out, is aimed at overthrowing the government and occurs largely within a state, although it may have violent repercussions that transcend territorial boundaries. Next, the professor focuses on the assorted means that insurgents can opt for in seeking to achieve their objectives. These include guerrilla wars, revolution and terrorism.

He explains that guerrilla wars are preferred by insurgents when they face stronger, better-equipped enemy forces against which a diffuse type of war is more effective. “Thus, as a strategy, guerrilla warfare avoids direct, decisive battles and instead, opts for a series of protracted but small skirmishes where the insurgents’ inferiority in terms of manpower, arms and equipment can be turned to an advantage by adopting flexible hit-and-run tactics and style of warfare…guerrilla warfare employs raids, ambushes and sabotage from remote and inaccessible bases in mountains, forests, jungles or territory of neighboring states”.

Another feature of guerrilla warfare analysed by Professor Agara is that of many modern states, which, in addition to their regular armies, train troops called special forces to confront non-conventional combatants in irregular warfare. He submits that “As a result of the special training in sabotage, explosives and selective destruction of targets and because cruelty and brutality unmodified and unsanctioned by rules of war under which regular armies operate are the enduring characteristics of irregular warfare, these elites’ military groups actually qualify to be called terrorists-in-uniform”. On the concept of revolution, the lecturer analyses it both as a means of achieving the objectives of insurgency or as an end of achieving far-reaching social and political outcomes often by violent means. Unlike social reform, a revolution aims at smashing “the existing status quo and replacing it with a better one while at the same time resolving the issue of class antagonism and contradiction.”

Perhaps because of our contemporary experiences in Nigeria, Professor Agara examines at greater length the phenomenon of terrorism. He identifies diverse forms of terrorism, including state terrorism, which refers to the use of terrorism by a state against its own population or state-sponsored terrorism, which is international terrorist activity sponsored by states through the provision of arms, training, safe haven or financial backing. Distinguishing between religious-motivated and politically-motivated terrorism, he notes that, although both employ the use of violence, the latter seeks to challenge the authority of the state without affecting the private rights of innocent parties, while the goals of the former are essentially “trans-temporal and the time limit of their struggle is eternity”.

Professor Agara identifies other features of religious-motivated terrorism to include choosing the targets of violence not for military values or reasons but rather for their impact on public consciousness due to the degree of brutality or element of surprise or suddenness; portraying the perpetrators of religious-terrorism as pursuing the cause of a ‘god’ and their opponents as consequently evil; and the propagation of the divine nature of religious terrorism, which is perceived as a struggle between good and evil.

Acts of terrorism, Professor Agara points out, are particularly deliberately geared to make the most damaging impact in order to draw the widest possible attention to the demands and exploits of the terrorists. He explains this thus: “Coupled with this is the fact that terrorist actions would be useless if not directed to attract attention, the attention of a specific in which a particular mode of fear is sought to be created. The violence of terrorism is not an end in itself. Rather, violence is employed precisely to create a sense of fear, terror and uncertainty in the people who are the audience of terrorism”.

Another interesting aspect of this lecture is the professor’s exhaustive examination of the nexus between terrorism and organised crime. He argues that the transition towards a more closely knit, globalised economy has also facilitated “the emergence of a transnational form of organized criminality, which has increased the possibilities of terrorists becoming involved in illegal business”. Insurgents increasingly exploit the opportunities provided by improved communication, advances in information technologies as well as greater mobility of goods and services across countries, among others, to participate in purely criminal activities.

At the level of operational modes of operation, the convergence between terrorist groups and organized crime cartels, according to Professor Agara, includes involvement in the trafficking or use of drugs; engaging in illegal trading activities through, for instance, the use of the black market to sell gold, diamonds and other precious minerals to fund their activities; the facilitation of their operations through forging documents such as traveling documents, passports and credit cards to ease their movements across different countries and kidnapping for ransom as the fastest and perhaps the surest way to acquire funds for criminals and jihadists”.

Other areas of convergence in the mode of Operation between terrorist groups and criminal gangs, which the author illuminates, include the use of intimidation, aggression and threats to extort money from members of the public including the payment of money by victims in turn for protection by the criminal elements; creation of front or screen companies to launder and legitimize laundering of and movement of money or funds acquired through shadowy sources of organized crime or other illicit activities.

Two forms of convergence by terrorist groups and criminal syndicates, pointed out by the Professor, include direct collaboration between criminal cartels and terrorist groups especially where both share similar religious ideology and beliefs or where such collaboration is a function of meeting a mutually beneficial economic activity or practical need.

Comparing the areas of convergence as regards the organizational methods of terrorist groups in contrast with criminal cartels, Professor Agara notes that these include the primacy of the pursuit, first and foremost, of pecuniary and monetary interests to the detriment of overtly political goals; an essentially hierarchical organizational structure by both; an organizational structure premised on a cell-like formation with each cell consisting of not more than 10 members and each cell enabled to function independently of each other. Furthermore, Membership into organised criminal groups and terrorist organisations is never advertised or announced, nor are written applications invited, with applicants shortlisted for interview. By virtue of their exclusivity, the membership is also exclusive, not open, but significantly limited with strict qualification or criteria such as ethnic background, kinship, race, criminal record, religious affiliation (particularly in the case of religious terrorism like ISIS,al-Qaeda and Boko Haram).

On recruitment of members, he notes that both members of terror groups and criminal gangs demand, in addition to basic qualifications in either criminal proclivities or extremist ideological bent, “potential members would also require to be sponsored by a high-ranking member of the group and must prove qualified by their willingness to perform any acts required of them, obey orders and keep secrets”. Ironically, although both terrors groups and criminal gangs are essentially lawless elements by definition, Professor Agara notes that the activities of members are guided by rules and regulations which they are expected to follow; both terrors groups and criminal cartels claim monopoly over particular territories over which they strive to maintain dominance; both types of groups do not hesitate as regards their willingness to exploit the use of illegal violence while both organized criminal gangs and terrorist organizations constitute an ongoing criminal conspiracy against the society but designed to persist through time and even after and beyond the lifetimes of the present members”.

In the last three sections of the lecture, Professor Agara rigorously interrogates the phenomena of secession and herders’ invasion, which he had earlier cited as components of the ‘triad of evil’ currently afflicting the Nigerian State. And in conclusion, he examines the implications of the widespread violence for the efficacy of the Nigerian State in performing its obligations, particularly of maintaining the safety of the lives and property of citizens. He argues that failed states are characterised by an implosion of states’ structures, which results in the incapability of governmental authorities to perform their functions, including providing security, respecting the rule of law, exercising control, supplying education and health services and maintaining economic and structural infrastructures”. Does he then arrive at the conclusion that Nigeria is a failed state?

Rather, he argues that the concept of State failure is a gradual unfolding of loss of state efficacy, which can be measured along a continuum, “as the state becomes progressively less capable of performing its functions and as a result becomes more and more ‘failed’. Complete state collapse is the ultimate, but rare result, while different stages of state failure can be encountered along the continuum”. Since he argues that the defining characteristic of state failure lies in the implosion of government institutions and the inability of any group to constitute the governing authority by effectively replacing the government in power, Professor Agara introduces a new category between failed and collapsed states to depict the Nigerian situation.

Of the Nigerian case, he submits thus that “While this may not be categorical, the fact that the institutions of the state still function, and are periodically contested for, may be believed to be the fact and reality of a failed state where such institutions have crumbled and, in some cases, are no longer in existence. Hence, the need to introduce another concept- to describe such states – as fractured states. Nigeria may be described as a fractured state since the institutional pillars on which the state rests are still ‘operational’ and visibly contested for, even though it has not adequately provided the public with the necessary goods and services, including security of lives and property”. How do we stem the complete slide of the Nigerian State from a fractured polity to a failed one or a collapsed State? That is a critical question facing both the operators of the Nigerian State, as well as those with specialisation in the study of complex, plural, federal societies like Nigeria such as Professor Babatunde Agara.