Weeks before, there had been protests in mainly some northern states, clamouring for the sack of the immediate past Chief Executive Officer of the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA), Farouk Ahmed, over sundry allegations of corruption. At the time, the question in the mouths of many was who were the sponsors of these protests, especially as it seemed many of the protesters probably knew next-to-nothing about the oil sector, upstream or downstream.

We have seen many such protests in the country, whereby many of the protesters carrying placards would turn them upside down, suggesting they were stark illiterates who could never have understood the reason for their joining the protests beyond the stipend they would be given for participation.

Despite the loudness of the protests, neither the Federal Government nor Ahmed was moved to action. Both went about their different duties.

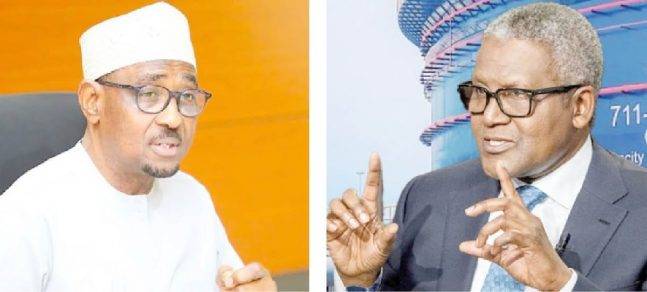

But all that was to change when Africa’s richest person and founder of the Dangote Group, Alhaji Aliko Dangote, joined the fray by making some grievous allegations against Ahmed. Dangote’s voice alone dwarfed the voices of the entire motley crowd that had been crying like John the Baptist in the wilderness. If the government did not hear, or pretended not to hear: not Ahmed. The former NMDPRA boss heard Dangote loud and clear, and immediately did what occurred to him to be the needful. He resigned. Thereafter, he tried to defend the allegations raised against him by Dangote.

Indeed, his action reminded me of the expensive joke that one of my bosses at the then Kingsway Stores, one Mrs Dina, an Ijebu woman who was hardworking to the core, used to crack whenever any of us fumbled at work. ‘’Kingsway a koko le e lo, ki won to fi ‘we da e duro’ (Kingsway would first send you away before following it up with your sack letter!)

But why did Ahmed not resign all this while? Could it be that Dangote’s voice was likely to attract the attention of the government, in which case he could have been fired, instead of the opportunity he had to honourably resign?

Just as we may never know whether we saw his exit at the time it came or not; we may also not know why he did not put forward his defence and stay put, if he knew he was indeed without blemish. Could he have reigned so that the government would simply close the case as usual and we move on?

Again, we may never have answers to these questions. What is clear at least as in the public domain is that he tendered his resignation on December 17, barely days after Dangote made public the damning allegations against him. A newspaper report gave what could be a possible clue as to why the NMDPRA boss eventually threw in the towel as it reported that the embattled Ahmed had earlier that evening met with President Bola Ahmed Tinubu at the State House, Abuja, for about 30 minutes.

Indeed, the newspaper described the resignation as ‘’unexpected turn of events’’. Perhaps unexpected because people had all the while thought Ahmed enjoyed the support of the government.

If Ahmed’s resignation was unexpected, then, how do we describe that of his counterpart at the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC), Gbenga Komolafe, who also turned in his resignation same day? Both Ahmed and Komolafe were appointed by the President Muhammadu Buhari administration in 2021 to lead the two regulatory agencies created by the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA). Their tenure should have expired next year.

However, if anyone had thought the government had been treating Ahmed’s matter with kid gloves, its swift replacement of the duo confirmed the contrary. Perhaps the government had only been shopping for their replacements all through the time it did nothing (at least in the eyes of the public) despite the cries for Ahmed’s probe and ultimate sack. This swiftness led to the president sending the names of two new chief executives for the NMDPRA and the NUPRC, namely: Saidu Aliyu Mohammed and Oritsemeyiwa Eyesan, respectively. This is commendable, given their strategic importance in the oil sector. No vacuum should be allowed in such strategic agencies.

If I had been ‘Ahmedcentric’ so far in this write-up, it is because, as I mentioned earlier, tongues had been wagging about Ahmed’s activities at the NMDPRA long before now. We have not heard that Komolafe did anything to warrant his sudden resignation alongside Ahmed’s. Moreover, as we would discover shortly, Ahmed’s matter appears hydra-headed or multidimensional.

Komolafe’s case is particularly pathetic because he was said to have raised the bar at NUPRC. He was said to have embarked on a series of reforms that border on regulatory transparency, community engagement, investment confidence, industry performance and international engagement. From the time he was appointed in 2021, he succeeded in increasing the country’s active drilling rig counts from barely eight to almost 70 by October, 2025. His efforts were said to have paid off with approvals in investments and capital inflow. He also did well with community engagement and took measures that reduced crude theft.

So, what could have led to his resignation?

The only thing I heard was that it was done for ethnic balancing? I do not believe this. This is why the government itself has to shed some light on Komolafe’s dark deeds at NUPRC (if any), to erase any doubt of ethnic balancing. After all, a Yoruba adage says it is the finger that sinned that is cut off (ika to ba se l’Oba nge). I do not think it is possible for anyone to carry vicarious liability in this matter.

Back to Dangote vs. Ahmed.

Dangote in recent times has been at daggers-drawn with the NMDPRA and particularly Ahmed, its head, that he accused of sleaze and economic sabotage by undermining local refining capacity in Nigeria, especially through the unbridled issuance of import licences for petroleum products, despite the capacity of local refiners to meet the country’s needs.

Africa’s richest person also raised what some people refer to as personal allegation against the NMDPRA boss. He alleged that Ahmed was living beyond his legitimate means, claiming that four of his children attend secondary schools in Switzerland at a cost of about $7 million.

Dangote concluded that this kind of expenditure raised questions about potential conflicts of interest and the integrity of regulatory oversight in the downstream petroleum sector. He subsequently submitted a petition to the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC), calling for Ahmed’s arrest, investigation and prosecution.

Ahmed, on his part, has tried to answer some of the questions raised by Dangote, particularly as they affect the education of his children. He said, “Three of my four children received substantial merit-based scholarships ranging from 40% to 65% of tuition costs.”

Beyond these scholarships, he explained that his father, a businessman, established a trust fund for the education of his grandchildren before his death in 2018. Apparently, he is taking advantage of this as well as what he called support from extended family, consistent with traditional Nigerian values of collective investment in education.

He added that when his three decades of accumulated savings (of about N48 million annually) and official compensation are considered, he cannot be said to be living beyond his means and that he has consistently declared his assets to the Code of Conduct Bureau since joining the public sector in 1991.

For me, I do not see any reason why Nigeria should continue to import petrol at the rate it did even up till last month. In November, last year, the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Ltd (NNPCL) said it had stopped importation of fuel. Melee Kyari, its then chief executive officer, said “Today, NNPC does not import any product; we are taking only from domestic refineries.”

However, figures from the NMDPRA showed that NNPC Limited and other marketers imported 52.1 million litres of petrol daily in November, 2025, despite the fact that consumption fell to 52.9 million litres per day in the month, down from 56.74 million litres per day recorded in October. This amounted to 1.563 billion litres for the month. NMDPRA said this was done because local supply could not meet up with demand, and especially with the festive season around the corner.

I know some people had invested in tank facilities during the period of fuel importation, but then, we can only try to strike a balance between their interest and the larger interest of the country. We cannot kill local refineries (just because of that), a thing we had been craving for, for decades.

Of course, I am also not oblivious of the potential threat that a single dominant player in the sector could pose to the economy. Even at that, we have to see it in the larger interest of the economy while the government tries to do some balancing act to avoid this.

To those who felt Dangote should not have mentioned the fabulous amount Ahmed allegedly spent on his children’s secondary education outside the country, because it is a personal affair, I think they missed the point. Dangote is a major tax payer; his Dangote Group paid N402 billion tax to the Federal Government’s coffers last year, at least as confirmed by the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS). Some other reports quoted N450 billion. Whichever, this is huge. He is therefore more than qualified to know how this is spent and should therefore not keep quiet when he feels a public official is spending above his means. Many public officials in Nigeria do. I do not think Dangote would have cited this if he had issues with a private citizen.

And, to those who have always felt Dangote is allergic to competition. While I am not in a position to deny or admit this, suffice it to say that it is impossible for a man who has established a $20 billion world-class refinery of Dangote Refinery status to be a gentleman. This is much more so in our kind of clime where the oil sector stinks to high heaven, with people that had been creaming off billions of money meant for fuel subsidy after they had ensured that all the public refineries became either dead or comatose. That business is not one for gentlemen because the stench in the sector is almost pervasive; with, perhaps, none exempts.

My conclusion: Ahmed’s resignation cannot be the end of the matter; the allegations against him must be investigated in the interest of natural justice, the economy and transparency and accountability in public office. Nothing short of this would do.

Culled from The Nation