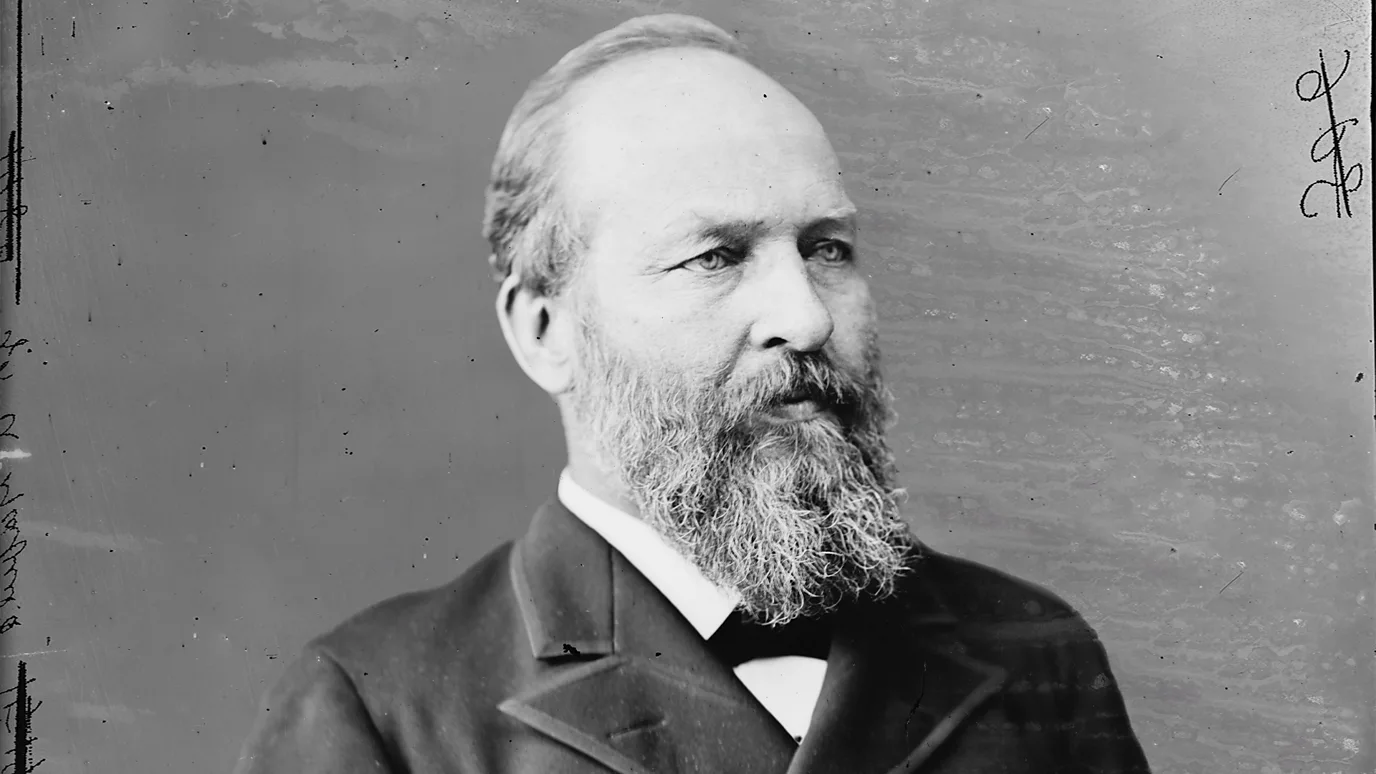

In the late 19th Century, President James Garfield promised progress and reform – but four months after his inauguration he was shot. New series Death by Lightning explores his life and legacy.

In the year 1880, the US stood at a crossroads. Would formerly enslaved people finally enjoy full rights as citizens? Could an entrenched patronage system – the doling out of federal government jobs to party faithful instead of the most qualified candidates – be reformed? At the Republican National Convention in June, James Garfield addressed these questions, beseeching the nation to fulfill its promises to all.

Hearing his eloquent speech, hundreds of delegates stood and roared in approval, before demanding that this congressman from Ohio be their candidate.

Garfield tried to refuse his party’s nomination. He insisted he had no desire for the presidency.

But the groundswell of support for Garfield – who’d risen to national office out of poverty, as Abraham Lincoln had, and performed heroics as a commander on the Union side in the Civil War – proved unstoppable, and in November 1880, he was elected the country’s 20th president.

What happened next is among the most tragic chapters in the annals of presidential history: shot four months after his inauguration, Garfield eventually died from sepsis. In her best-selling work on Garfield, Destiny of the Republic: A Tale of Madness, Medicine, and the Murder of a President, author Candice Millard expertly recounts the story. The award-winning book was the basis of a two-part documentary, The Murder of a President, broadcast in the US on PBS in 2016.

Confronting a big ‘what if’ in US history

Now Netflix plays host to an ambitious – and lavish – new adaptation of Millard’s work. Death by Lightning, a four-part drama written by Michael Makowsky and starring Michael Shannon as James Garfield and Matthew Macfadyen as the man who shot him, Charles Guiteau. What might viewers take away from the show? “I hope it’s a reminder that you don’t have to have a big event to change the course of history,” Millard tells the BBC. “In this case, the combination of one man’s madness and another’s ignorance and petty ambitions devastated an entire nation.”

Long before he shot Garfield, Guiteau exhibited signs of mental instability, yet he was never treated nor confined in that era of rudimentary psychiatry. As for the arrogant physician who insisted on supervising the president’s care after he was shot, Dr Wilfred Bliss scoffed at the latest antiseptic method for treating wounds, using unsterilised instruments and even his bare finger to probe the hole near Garfield’s spine. Blame for the president’s death can be laid firmly at Bliss’s door, as Millard lays out in painful detail.

Both men cared very much about being known. One propels himself to the highest office in the land, whereas the other courts greatness and never achieves it – Michael Makowsky

Screenwriter Makowsky picked Millard’s Destiny of the Republic off a two-for-one sale table, took it home and read it in one sitting. He immediately envisioned a television drama. “I got the author on the phone, and at first she said no,” he tells the BBC. “I had to persuade her to trust me with the project.”

Makowsky could point to his previous experience dramatising true events. A true-crime film he wrote for HBO, Bad Education – about a larcenous school superintendent, Frank Tassone, from Makowsky’s hometown of Roslyn, New York – won an Emmy award in 2019. Telling Garfield’s story meant confronting an enduring historical “what if”: had the promising president not been targeted by an assassin, what could he have accomplished? “He could have been one of our most remarkable presidents. He had a magnificent intellect. The fact that he’s been relegated to an obscure footnote is a tragedy.” Makowsky says.

Makowsky’s crucial task was to sift through Millard’s detailed dive into the history of the assassination and construct a narrative appealing to TV viewers. Destiny of the Republic includes sections on Republican Party factionalism, the antiseptics preferred by British surgeon Joseph Lister and Alexander Graham Bell’s invention of an early metal detector, used eventually to search for the bullet in Garfield’s body.

Makowsky chose to focus on the contrasting journeys of Guiteau and Garfield. “Both men cared very much about being known,” he said. “One propels himself to the highest office in the land, whereas the other courts greatness and never achieves it.”

The killer’s motivation

By turns Guiteau failed as a lawyer, a journalist and an evangelical preacher. He even flopped at the free love commune he joined; no woman would sleep with him, as Millard recounts. Yet he always believed God intended him for a grand purpose. Guiteau became obsessed with Garfield after the congressman’s unlikely nomination, and travelled to New York in the summer of 1880, determined to play a crucial role ensuring his victory in the general election. Guiteau harassed the staff at Garfield’s New York campaign office until he was allowed to give a single rambling speech endorsing the candidate.

Garfield vocally opposed the spoils system of handing out lucrative posts to supporters, yet Guiteau believed in it fiercely. He expected that, in exchange for his backing, Garfield, now president, would give him a key post. Ambassador to France was his first choice. The deluded man travelled to Washington, and appeared at the White House every day with hordes of other insistent office seekers. Guiteau even came face to face with his hero once, in the president’s office, where he handed Garfield a copy of his election speech, with “Paris Consulship” scrawled on it, and a line connecting those words to his name.

Garfield, meanwhile, embarked on an ambitious agenda for his presidency, including upgrading the US Navy, aiming to expand trade with Latin America, and advocating for civil rights. He appointed the once-enslaved social reformer Frederick Douglass as recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia, the first African American to hold a prominent federal office. At the same time, Garfield also had to face down Roscoe Conkling, Republican senator from New York, arguably the most powerful politician in the nation, thanks to his indirect control of the lucrative customs revenue flowing into the port of New York. Conkling didn’t like Garfield’s progressive instincts nor his opposition to the spoils system. He’d already imposed on candidate Garfield his associate Chester A Arthur, to be vice president. Now Conkling sought to block Garfield’s Cabinet picks.

Michael Shannon does an astonishing job of capturing Garfield’s brilliance and dignity but especially his decency, which is something I really cared about – Candice Millard

After Guiteau’s strange manner and erratic outbursts got him blocked from entering the White House, he began showing up at the office of Secretary of State James Blaine. One day he importuned Blaine directly, only to be told in no uncertain terms he would never be given a position in the Garfield administration.

Without money or prospects, Guiteau retreated to his shabby boarding house. There, lying on his bed, he had what he later called a divine inspiration: Garfield was not a “true” Republican, unlike his vice president. In his deluded state Guiteau then concluded it was up to him to kill Garfield, and make Arthur the nation’s leader.

The president, unfortunately, was not difficult to target. He walked everywhere unprotected, even though John Wilkes Booth had killed President Abraham Lincoln a mere 16 years before.

“Assassination can no more be guarded against than death by lightning,” Garfield wrote in a letter, “and it is best not to worry about either.” After stalking Garfield for a few days, Guiteau shot him at the Baltimore and Potomac railroad station in Washington DC on 2 July 1881.

Garfield’s phrase “death by lightning”, stuck with Makowsky, who chose it for his title. He collaborated with director Matt Ross on the choice of actors, and felt lucky to recruit for the Garfield role Michael Shannon, and, as Guiteau, Matthew Macfadyen, fresh off his star turn playing the hapless schemer Tom Wambsgans in Succession.

“We punched above our weight when it came to casting,” said Makowsky. After visiting the set during the filming in Hungary, author Millard agreed. “Michael Shannon does an astonishing job of capturing Garfield’s brilliance and dignity but especially his decency, which is something I really cared about,” she says. “And Matthew Macfadyen, whom I’ve watched and admired in so many roles, simply becomes Charles Guiteau, in all of his strangeness, delusion and heartbreaking madness.”

Parts of Makowsky’s script hew closely to the history; he takes artistic license at other points. Guiteau’s one meeting with the president at the White House was, in reality, likely formal and brief, but in Makowsky’s reimagining the deranged man has a chance to express all his desperate yearnings to Garfield. And Macfadyen delivers a powerful performance. “I’m your man,” the actor says, his voice trembling, his eyes full. “Help me to succeed like you did. Open the door… I’m begging you. Tell me how I can be great too.”

Makowsky hopes the audience will have some empathy for Guiteau despite his terrible deed, for which he was hanged on 30 June 1882. “It would be easy to write him off,” the screenwriter says. “But the extreme alienation he experienced in the world, the constant rejection, it obviously hurt him and there existed no mechanisms to help him. The country ultimately paid the price for that.”

Garfield’s legacy

Michael Shannon plays Garfield in the new Netflix miniseries Death by Lightning (Credit: Netflix)

Garfield did make a difference. The nationwide grief over his murder, aged only 49, galvanised demands for civil service reform. The public recognised that Guiteau’s rage – although fuelled by his delusions – began when he was denied a job he believed he was owed. And Arthur, now president and mourning his able and likable predecessor, renounced the corrupt spoils system that had elevated him. When Congress passed the Pendleton Act in 1883, creating merit-based standards for federal government employment, Arthur signed it into law.

“This began the professionalisation of the federal bureaucracy, ensuring that Americans’ transactions with their government would not be influenced by their personal politics,” biographer CW Goodyear, author of President Garfield: From Radical to Unifier, wrote. “Its yields in the generations since have been immeasurable.”

BBC