One afternoon, my phone buzzed.

“Hello sir,” I said.

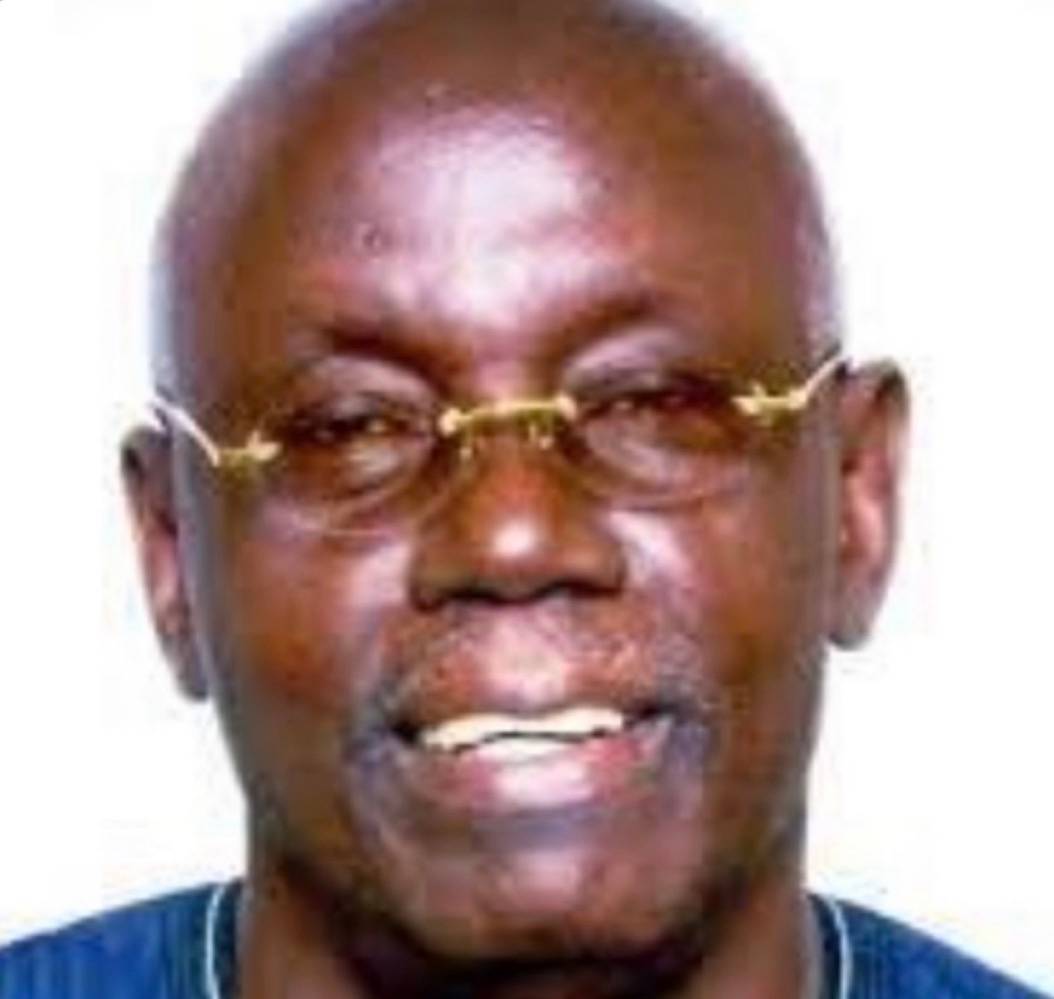

“Hi Sam, this is Dan the butcher calling.” The great Dan Agbese’s voice was unmistakable, and so was his cheer.

He was responding with thanks to my short tribute on his 80th birthday.

I was a staff member of Newswatch, a magazine that revolutionsied the journalism craft, in writing style, investigation and essays. Above all, it endowed a generation with courage in the written word.

Ahead of the cream of its editors was Dele Giwa, perhaps the most colourful journalist we have ever had. I knew Dele Giwa from a distance, meaning I read all his columns I could access. I joined the magazine after his tragic passing.

My first experience in the company was not with Newswatch, though. When I was hired, Newswatch had been proscribed by the IBB regime, and the editors floated a soft sell known as Quality under the editorship of May Ellen Ezekiel, who tugged the popular fancy with her edgy column under the name MEE.

I worked with her as a rookie but hoping to join Newswatch when it was reborn. One afternoon, all the staff were summoned to the office of editor-in-chief Ray Ekpu. Word had reached the company that the IBB regime would unban the paper the next day, and we had to be ready for the new edition. I had seen the other top editors and reporters around, but I never had real interaction, including Yakubu Mohammed, Soji Akinrinade, Dele Omotunde, who left for the Alfred Friendly Press Fellowship that this essayist would also attend later in his career, Nosa Igiebor, Dare Babarinsa, Onome Osifo-Whiskey, Chuks Iloegbunam, Anietie Usen, Ben Edokpayi, Louisa Aguiyi-Ironsi (daughter of Nigeria’s first army chief) and fellow reporters like Peter Ishaka, Janet Mba and Sam Loco Smith.

As Ekpu presided, I was like a fly on the wall, observing for the first time the interplay of ideas that brewed the magazine on the stands every Monday. It was the first time I saw Dan Agbese up close. He was in his element, cracking jokes and sizzling with ideas simultaneously, and it was on his lips I was reminded of the phrase Kwarangida, which I first heard from the lips of good friend Solomon Olaniyan during my youth service in Kano.

After various writers had been assigned their stories, Ray brought up the society page known as Newsliners. Dan edited the page, and he looked towards me and said “Sam, who do you have?” I was flummoxed, though he said it with a smile. How was I to have candidate for that page? He asked me to see him later, putting me at ease.

I was not yet a staff, but on a stipend. I was just happy to be there. When I met Dan in his office on the top floor on Oregun Road, he asked me to read past issues, and he suggested a few names I should follow, including Alao-Aka Bashorun, who had just become the president of Nigerian Bar Association, Oprah Benson – the Iya Oge of Lagos. I dropped down to the newsroom with no clue how to proceed. I asked someone for Alao Aka-Bashorun’s office address. I had it and was on my way to the bus stop when I saw a Volkswagen Beetle pull up just beside me and it was the actor Funso Alabi, Mr. Gyang in the hugely popular Teevee show Second Chance and perennial Soyinka favorite on stage.

I said hi and told him casually where I was headed. And he said, “That’s where I am going.”

He was a godsend. He saved the sweat and ache of bus ride and the intellectual toil of mapping the office in a geographic chaos of Lagos. Alabi was also a candidate for Newsliners, and once we arrived at Aka-Bashorun’s office, I interviewed him. Femi Falana was a lawyer in his chambers. What a miracle. A free ride, freedom from Lagos wear and tear, and two celebrities for my page. The next day, I clasped Iya Oge at an event at Airport Hotel. A day after I met the owner of Supreme Stitches, a fashion designer who is now Nigeria’s wealthiest woman, Folorunsho Alakija.

I was told in the newsroom that Dan was the most difficult editor to impress. Having had a hard time with May Ellen in Quality, I was expecting Dan to query me on my first copy. Moments later, I saw his personal assistant come downstairs but he never looked my way. I was waiting for him to make the turn at the end of the newsroom but he proceeded into the compugraphy room. When he returned, I looked away nervously, hoping to hear my name. When I looked back, he had disappeared.

I was even more nervous for it. I walked to the compugraphy room to see if he had rewritten everything. I saw my copy. Clean almost as I had written them, except the part about Aka-Bashorun being married with children. I asked the staff there whether there was any problem with the script. He was aghast at my impudence. Dan had sent a copy and I was asking if there was a problem? I walked away, my nerve more powerful than my whole body.

I was to learn that Ray loved elegance, Dan poetry, and Yakubu a straight story. Agbese was my real first editor. I would not say I learned how to write from him. I would say, he gave me the confidence to write on my own terms. I had a problem with May Ellen because she had no patience with a rookie. I had to ask Iloegbunam and Usen to show me the Newswatch style. I came off understanding that I had to be myself. I had to forge my own personality on the page, in diction, rhythm, cadence and angles.

Agbese let me be. Since I was writing mainly cultural stories, he was my boss. I remember his knack to cast headlines. I did a story on monitor lizards, a totem in Orogun village in Delta State, and he headlined it: Gods on Four feet. Another story marked the 9th edition of the Trade fair, and he titled it: Fairer in the Ninth. I enjoyed Newsliners, and my constant critic and appreciator was Femi Macaulay, now an essayist and editorial board member of The Nation, who was at the ready with a comment. I was always on the move, at night, at parties, offices, sports arena, et al. I was doing other stories, but my impulse for politics was overpowering. I wanted to write a cover, preface to cover, etc. I was getting ahead of myself. I had not spent a year.

One evening, Nosa Igiebor then observed why I was not paying more attention to the page. “Since we started that page, you are by far the best who has handled it,” he said.

I thought I was just doing a routine job. I had read that page from outside and I was wowed by my predecessors.

To be the best? I was emboldened, not to continue but to move on. “Sam, I know you are deliberately doing a bad job.” That was Dan. He did not tell me I was the best, he merely said he had not had a problem with my script since I started doing it. A rare compliment from the butcher. Yakubu – we called him Yaki -, echoed Nosa’s sentiment.

Dan presided over our editorial meetings every Friday, and I also learned how stories were minted, perspectives born, and how a fest of ideas led to big stories. In one edition, I wrote the first story in the magazine under the Life section, and the last, Newsliners, one in the nation section, a Noriega piece in the International section and a culture story on fights in the music industry.

One evening, Dan’s assistant came to me with a post-it note with words of commendation from Agbese. It ended with congratulations. That was the clincher when Lewis Obi hired me as staff writer in African Concord.

I had learned from Dan the butcher, who was so called because he had a knack for tight editing. I was in heaven with him. I never experienced such cuts. You might write a 1000 word- piece and he could cut it to 300 and you would not query his skill. You admired your butcher, blood and all. He cut not to slaughter but to heal.

He wrote with poesy. When Kogi and Akwa Ibom State were created. He described Kogi’s sound: “just like tin drum.”

For Akwa Ibom, he wrote Akwa was like the sound of a stone released from a catapult. Ibom the sound of the pebble dropping into the pond. In recalling Giwa’s death he sang, “in this business of minding other people’s business, tragedy is a way of life.”

I met with him quite a number of times after I left Newswatch, and his bonhomie and visceral charm remained unassailable. I recall seeing him at a party in late Joe Agbro’s home in Lagos, and he would not live down his experience with starch and banga soup, and wondered when we would relive the experience. We would never share starch again but his memory sticks forever. Good night, Dan the man.