…as MTN sets the pace for African development

Abolaji Adebayo

The battle for Africa’s story is a battle for Africa’s future

“While the rest of the world has an agenda for Africa, Africa has no agenda for the rest of the world,” declared Professor Admire Mare, Head of the Department of Communication and Media at the University of Johannesburg, his voice echoing through the auditorium at the MTN Media Innovation Summit.

This stark assessment captures a profound truth about Africa’s place in the global information ecosystem, a reality where international media giants like BBC, CNN, and Al Jazeera have historically defined how the world sees Africa, often through a lens of crisis, poverty, and corruption.

This persistent misrepresentation and what Professor Mare terms “White hegemony” in media narratives have crippled effective media diplomacy and agenda-setting on the continent. But across African nations, a powerful counter-movement is emerging, driven by recognition that narrative control is fundamentally about mind control—that those who tell the stories ultimately shape minds, markets, and futures.

At the forefront of this transformative effort is MTN, through its Media Innovation Programme (MIP), which has become a critical platform for fostering collaboration between Africa’s two largest economies: Nigeria and South Africa. As Funso Aina, Senior Manager for External Relations at MTN Nigeria, emphatically states, “If both countries get it right, the entire continent gets it right.” This recognition that narrative sovereignty is essential to continental progress represents a seismic shift in how African media professionals approach their work, not merely as reporters of fact but as architects of Africa’s developmental agenda.

Single Story Dilemma: How Foreign Narratives Have Defined Africa

The phenomenon that Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie famously termed “the danger of a single story” has manifested with particular potency in international coverage of Africa. For decades, foreign correspondents and media outlets have presented a monolithic portrait of the continent—one defined predominantly by conflict, poverty, corruption, and disease. This persistent framing has had real-world consequences, affecting foreign investment decisions, tourism patterns, and even international policy toward African nations.

Professor Rene Benecke, Head of the School of Communication at the University of Johannesburg, emphasised that challenging this reductive narrative is both a professional and ethical imperative for African journalists.

“Our role is to tell the fuller, richer stories of the continent,” she asserts. This requires moving beyond reactive reporting that merely counters negative stereotypes to proactive agenda-setting that highlights Africa’s diversity, innovation, and complex realities.

The economic impact of distorted narratives cannot be overstated. When international media consistently frame Africa as “poverty-stricken” despite the continent being “full of natural resources without which the West and the rest of the world may not survive,” they create a perceptual gap that directly affects economic relations. This narrative disconnect often means that African resources are extracted while African value addition remains underdeveloped, perpetuating cycles of dependency rather than fostering industrial transformation.

The problem is compounded by what Professor Mare identified as a reliance on foreign media for information about the continent itself.

“Most people do not know what is happening in this continent because we rely on foreign Media,” he observed. This dependency has created a situation where Africans often understand their own realities through filtered lenses that prioritise foreign interests and perspectives, undermining pan-African solidarity and collaborative problem-solving.

Navigating the New Media Landscape

Today’s media environment presents both unprecedented challenges and unique opportunities for African storytellers. Professor Benecke introduced delegates to the concept of the “BANI world”—an environment characterised by brittleness, anxiety, non-linearity, and incomprehensibility. This framework captures the volatile nature of modern communication ecosystems, where digital platforms can amplify messages instantly but also distort them beyond recognition, where information spreads rapidly but so does misinformation.

In this complex landscape, the tools of narrative control have become more accessible than ever before. As Professor Mare notes, “We are the media; we should not depend much on the traditional media to set the agenda. We are all media.”

This democratisation of storytelling means that African journalists, content creators, and even ordinary citizens now have the potential to contribute to a more nuanced continental narrative, but realising this potential requires strategic collaboration and capacity building.

The BANI framework is particularly relevant for understanding Africa’s media challenges. The continent’s information environment is indeed brittle, apparently stable narratives can shatter suddenly when new voices emerge. It is anxious with journalists working under significant pressure, including safety concerns, economic constraints, and political pressures.

It is non-linear, small local stories can rapidly escalate into continental conversations. And it can seem incomprehensible, with multiple perspectives competing for attention across diverse linguistic and cultural contexts.

Navigating this environment requires what Professor Benecke described as “creative problem-solving, adaptive thinking, responsible communication and multidisciplinary collaboration in an era dominated by artificial intelligence and algorithmic biases”. The institutions that succeed in this space will be those that can combine the credibility of traditional journalism with the agility and innovation of digital native content creators.

MTN MIP: Building Capacity for Narrative Change

Recognising the strategic importance of media in shaping Africa’s future, MTN has made significant investments in building journalistic capacity across the continent. The MTN Media Innovation Programme (MIP), launched in 2022 in collaboration with Pan-Atlantic University’s School of Media and Communication, represents a comprehensive approach to addressing the challenges facing African media.

This six-month fully funded certificate fellowship is designed to equip media practitioners with the skills and knowledge needed to navigate the evolving media landscape. As Tobe Okigbo, Chief Corporate Services & Sustainability Officer at MTN Nigeria, explained, “When we launched MIP in 2022, our goal was to enhance media professionals’ reporting capabilities and deepen their understanding of the technology sector, empowering them to become true media innovators.”

The programme has grown significantly since its inception, now including collaborations with the University of Johannesburg that facilitate crucial Nigeria-South Africa exchanges with the launch of Pan-African MIP.

The structure of the programme is specifically designed to foster pan-African connections and perspectives. Fellows spend 33 days in classroom sessions, participate in a seven-day study visit to South Africa, receive training at MTN Nigeria and Group headquarters, and visit innovation hubs.

This blend of theoretical knowledge, practical exposure, and cross-border networking creates a unique learning environment where media professionals can develop the skills needed to tell more complex African stories.

The impact of the programme is evident in testimonials from participants. Amarachi Ubani, Diplomatic Editor at Channels Television, described the sessions as “illuminating and life-changing,” transforming his “understanding of the media landscape in Nigeria. For Yemi Adebayo, MIP-4 Governor and AIT broadcaster, the programme reshaped his view African journalism and why Africa should be information independent.

Vanessa Ukamaka Richard-Bassey, Head of Programmes at Sparkling 92.3 FM, also admitted her views evolved after attending MIP sessions.

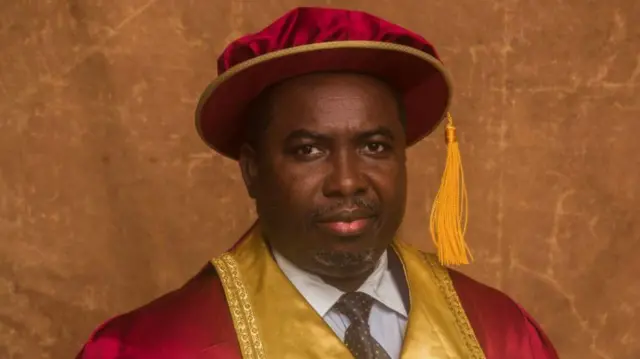

Despite being an ICT reporter, Abolaji Adebayo, ICT Editor at New Telegraph, admitted the programme offered insights even experts rarely share in interviews.

“Some of the things we learned at MIP aren’t disclosed publicly, some are even confidential. It broadened my understanding of the African media landscape far beyond what I knew before.”

These responses highlight how capacity building extends beyond technical skills to affect fundamental mindset shifts, essential prerequisites for narrative change.

Isaac Ezechukwu, Director of Professional Education at Pan-Atlantic University’s School of Media and Communication, describes MIP as “one of Africa’s most transformative media education initiatives.” He emphasised the need for increased investment in media education from governments, corporate partners, and educational institutions, noting that such support is essential to repositioning the media as “a vital driver of national development and an infrastructure for deepening public trust.”

Nigeria and South Africa: The Continental Powerhouses and Their Media Diplomacy Role

The strategic focus on Nigeria-South Africa collaboration within MTN’s media initiatives reflects a broader recognition of these nations’ outsized influence on continental affairs. Together, they represent Africa’s largest economies and most substantial media markets, giving them unique capacity to shape pan-African narratives.

The diplomatic dimensions of this media partnership were highlighted when Nigerian and South African high commissioners jointly addressed the Media Innovation Programme fellows. Ambassador Alexander Ajayi, Nigeria’s High Commissioner to South Africa, and Ambassador Thami Museleko, South Africa’s High Commissioner to Nigeria, both emphasised the media’s critical role in fostering pan-Africanism and changing negative stereotypes.

Ambassador Museleko stressed the need to “build trust between government and the people,” noting that changing continental stereotypes requires objective reporting on issues that matter. This government-media partnership is essential for advancing initiatives like the African Union’s Agenda 2063 and the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which require broad public support to succeed.

The business community has also recognised the importance of improved media collaboration between the two nations. Diana Games, Chief Executive Officer/Director of the South Africa/Nigeria Business Chamber, emphasised the economic benefits of accurate storytelling, encouraging journalists to “keep retooling their skills” to better report on the gains made in bilateral trade between the two countries.

Churchill Otieno, President of the African Media Forum, represented by former Editor-in-Chief, Mathatha Tsedu, challenged African journalists to “report Africa for Africa for the world,” emphasiding their role in countering stereotypes. Tsedu identified a fundamental prerequisite for narrative change: “There has to be a seismic change in our own psyche as Africans. We must love ourselves before we can change the perception about ourselves.” This insight highlights how internalised negative narratives must first be overcome before meaningful external narrative change can occur.

Forging a Unified Front: Practical Steps Toward Collaborative Storytelling

The theoretical case for media collaboration is compelling, but what does it look like in practice? The MTN Media Innovation Summit identified several concrete strategies for building a unified African media front.

First, there is a need to develop context-specific communication frameworks that can guide media professionals in different regions. As demonstrated by International Alert’s work in North-West Nigeria, such frameworks help journalists identify and replace harmful narratives with positive messages that foster unity, resilience, and nonviolence.

This approach involves tailoring content for diverse audiences, using trusted local voices, and delivering inclusive, culturally relevant messages through accessible platforms.

Second, effective collaboration requires establishing communities of practice where media professionals can continuously exchange knowledge and co-develop strategies. The Community of Practice (CoP) model used in Nigeria, which brings together media professionals, legal experts, government officials, community and religious leaders, and civil society actors on platforms like WhatsApp, demonstrates how sustained engagement can overcome initial scepticism about shifting from sensational to constructive storytelling.

Third, narrative change must amplify marginalised voices, particularly women and youth, who have traditionally been excluded from agenda-setting. As Sunday Momoh Jimoh, Project Manager at International Alert Nigeria, noted, involving women survivors of violence in sharing their stories has “helped shift public perceptions and influence the media’s approach to covering gender-based violence.” This inclusive approach ensures that new narratives reflect the full diversity of African experiences rather than simply replacing elite-dominated foreign narratives with elite-dominated African ones.

Fourth, African media must leverage technological innovation to create more compelling and accessible content.

The MTN Innovation Lab, which fellows visit during their South Africa study tour, showcases technologies like 5-Gigaverse, AI-driven personalisation, and autonomous networks that can transform how stories are told and consumed. Embracing these tools is essential for competing in an attention economy dominated by global platforms.

Finally, sustainable narrative change requires developing new business models for African media. The economic constraints facing journalism across the continent, declining newspaper circulation, retrenchments, and digital disruption, compromise independence and quality.

Addressing these challenges through innovative revenue streams and funding mechanisms is essential for building media institutions that can prioritize African agendas without being compromised by commercial or political pressures.

Media Diplomacy and Africa’s Global Positioning

The concept of “media diplomacy” featured prominently in the MTN Media Innovation Summit, reflecting growing recognition that narrative sovereignty is not just about cultural pride but strategic global positioning. As Professor Kammila Naidoo, Executive Dean of the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Johannesburg, noted, the summit provided a platform for examining how both traditional and digital media can “strengthen African agency in global affairs, foster regional cooperation, promote media diplomacy and counter threats of misinformation and online polarisation.”

This diplomatic dimension of media collaboration takes on particular significance as South Africa prepares to host the G20 Leaders’ Summit in November 2025. Professor Naidoo described this as “an important moment to shape and position an African agenda, showcase its strengths, and impact international discourse.” Without coordinated media efforts to ensure African perspectives are represented in coverage of such high-profile events, the familiar patterns of external narrative control are likely to reassert themselves.

The relationship between media diplomacy and developmental objectives is particularly evident in initiatives like the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which requires sophisticated communication strategies to build public understanding and support across diverse nations. Similarly, Agenda 2063, the African Union’s strategic framework for inclusive and sustainable development, depends on media partnerships to translate high-level policy concepts into relatable narratives that inspire collective action.

MTN’s sustainability strategy, framed as “Doing for Tomorrow, Today,” aligns with these broader developmental objectives. As MTN Group Executive on Sustainability and Shared Value, Marina Madale, explained, this includes commitments to achieving Net Zero emissions by 2040, driving inclusive growth, skills development, and proactive online safety. By supporting media innovation, MTN recognises that achieving these sustainability goals depends partly on effective storytelling that engages stakeholders across sectors.

From Narrative Recovery to Agenda Setting

Reclaiming African narratives represents an essential first step, but true progress requires moving beyond defensive positioning to proactive agenda-setting. This involves not just challenging negative stereotypes but actively defining Africa’s priorities, values, and aspirations on the continent’s own terms.

The evolution of messaging in peace building initiatives in Northern Nigeria illustrates what this transition can look like in practice. Initially focused on countering violence and promoting access to justice, messaging has become more nuanced over time, “incorporating climate-related conflict, natural resource governance, and restorative justice.” The tone and delivery have also shifted to reflect local idioms, religious teachings, and culturally resonant symbols, making them more effective and community-owned.

This model of adaptive, context-sensitive messaging provides a template for broader narrative efforts across the continent.

The role of educational institutions in sustaining this work cannot be overstated. Universities like Pan-Atlantic University in Nigeria and the University of Johannesburg in South Africa provide essential intellectual infrastructure for media innovation through research, curriculum development, and creating spaces for cross-border dialogue. Strengthening these institutions and their collaborations is essential for developing the next generation of African storytellers.

Corporate partners like MTN also have a vital role to play beyond initial programme funding. As Funso Aina noted, MTN’s commitment to media capacity building reflects recognition of journalists as “society’s most critical watchdogs.” This understanding that robust media ecosystems benefit businesses as well as societies suggests potential for sustainable corporate support that extends beyond traditional corporate social responsibility to strategic investment in the information landscape.

For individual media practitioners, the path forward involves embracing what Professor Benecke terms “responsible communication” in the BANI world. This includes developing greater digital literacy, understanding algorithmic biases, practicing ethical journalism amidst economic and political pressures, and building the resilience needed to navigate an increasingly complex information environment.

Birthing the New Narrative

“The old is dying, but the new cannot be born,” Professor Mare observed, capturing this transitional moment in African media. The familiar patterns of foreign narrative control are indeed losing their legitimacy, but new authentically African narratives have yet to be fully realised. Bridging this gap requires concerted effort across multiple sectors and nations.

The collaboration between Nigerian and South African media professionals, facilitated by initiatives like the MTN Media Innovation Programme, represents a promising foundation for this new narrative ecosystem. By combining Nigeria’s demographic weight and cultural influence with South Africa’s advanced media infrastructure and technical expertise, these two powerhouse nations can create a gravitational field that draws other African voices into a collaborative orbit.

The ultimate goal is not to replace negative foreign stereotypes with positive African ones, both approaches remain trapped in reactive posture, but to develop such rich, diverse, and complex storytelling that simplistic narratives become impossible to sustain. This requires moving beyond what Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie identified as the “single story” to embrace the multitude of stories that reflect Africa’s reality.

As Africa stands at the threshold of what many have termed “the African century,” the ability to shape how the continent’s journey is understood, by Africans themselves and by the world, will significantly influence developmental outcomes. From attracting investment to fostering innovation, from strengthening democracy to promoting cultural exchange, narrative sovereignty underpins progress across domains.

The words of Professor Mare serve as both warning and inspiration: “We are the media; we should not depend much on the traditional media to set the agenda. We are all media.” In this recognition of collective responsibility lies the seed of transformation, the understanding that rewriting African narratives is not just the work of professional journalists but of all who believe in Africa’s potential to define its own destiny.

Through sustained collaboration, strategic investment in media capacity, and a steadfast commitment to telling “the fuller, richer stories of the continent,” Nigeria, South Africa, and their partners across Africa are gradually assembling the narrative infrastructure needed to set the continent’s agenda for development. The birth of this new narrative ecosystem, no longer brittle but resilient, no longer anxious but confident, no longer incomprehensible but coherent, may well prove to be one of the most significant developments in Africa’s 21st-century renaissance.