By Festus Adedayo

Words are sacred sovereign objects. This sacredness makes them very essential to democratic freedom. In his poem, The Word Is An Egg, great Nigerian poet and dramatist, Niyi Osundare demonstrated the primacy of the word, whether written or spoken. To show the uniqueness of the word, Osundare’s Yoruba people say, like the broken egg, when you break the shell of the word by uttering it, it dissolves into nothingness. Both the one who utters it and the word itself are then never the same. Believing that the word is sacred, Yoruba transfer that sacredness to the African giant pouched rat (Okete). Whatever this giant rat tells the earth when it is digging its hole, it must comply, they believe. The Yoruba chant this belief in incantations that decree abidance to their command. Thus, drawing largely from the cosmology of his people, Osundare said the word predated man and even the world. “In the beginning was not the word/In the word was the beginning” he wrote. In the world of this poet, the word is omnipotent and omnipresent. The word is creation and the creator.

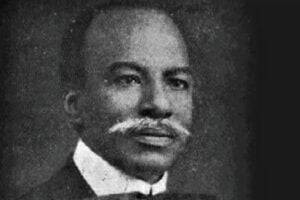

By granting presidential pardon to Herbert Macaulay, Mamman Vatsa, Ken Saro-Wiwa and others last week, the Nigerian president seems to affirm the primacy of the word. Essentially, what unites these three great Nigerians is their use of the word, spoken and written. Macaulay, for instance, apart from being a Nigerian nationalist, politician, surveyor, engineer and architect, he was also a journalist and newspaper founder. It must be said that virtually all nationalists in the colony were journalists. Realizing the power of the word, especially the written word, against colonialists, nationalists crusading for independence not only founded newspapers for this purpose, the word became their weapon of war. Ernest Sese Ikoli, Nnamdi Azikiwe, Obafemi Awolowo, S. L. Akintola etc. were all journalists whose arsenal against the colonizers was the written word.

From 1898 when he disengaged from public service, Macaulay joined the anti-colonial government forces. In the service of this quest, he co-founded the Nigerian Daily News newspaper where he bore his fangs against the colonial government. Some of his pieces included one he entitled “Justitia Fiat: The moral obligation of the British Government to the House of Docemo” and “Henry Carr Must Go”. The newspaper also became the platform he deployed to attack his political opponents and ex-associates like Henry Carr and Adamo Akeju, the Obanikoro of Lagos. In the same vein, Macaulay had a very deep animosity for Sir Hugh Clifford, the colonial governor of Nigeria from 1919 to 1931 who succeeded Sir Walter Egerton, the Governor of Lagos Colony from 1904 to 1906. When Clifford was leaving Nigeria, Macaulay wrote, in the Lagos Weekly Record newspaper of May 2, 1925, which he titled, ‘The Incorrigibility of Sir Hugh Clifford’: “Sir Hugh is about to bid final good-bye to Nigeria and he would undoubtedly leave his marks as the greatest talkee, talkee governor that Nigeria could boast of, for his addresses to the legislative council are volumes of gaseous talks and many a times he repeats himself in his desire to make his address bulky; at other times, he starts from the sublime and ends in the ridiculous.”

What shot Macaulay to the fore of anti-colonial struggle was actually the Amodu Tijani Oluwa land matter. The uncommon zeal with which he pursued the land issue on the side of Oluwa riled the British. Acting as Oluwa’s interpreter and private secretary, Macaulay stood in opposition to the British in their bid to compulsorily acquire Oluwa’s land in Apapa, with his testimonies. He went with him to the Privy Council in London and granted a press interview to the Daily Mail where he claimed that 17 million Nigerians saw Oba Eleko Esugbayi as their king and that he owned all the revenue that the colonial government spent. It subsequently led to the suspension of Eleko Esugbayi by the colonial government.

Macaulay’s adversarial journalism eventually led to his travails in the hands of the colonialists. He was notorious for the network of informants he kept who, for handsome fees, passed stolen sensitive information from the colonial government to him. These included minutes from colonial government meetings. He then got them published as exclusive stories damaging to white rule in newspapers that he was acquainted with. For this, Macaulay was nicknamed Wizard of Kirsten Hall.

By the twilight of the 1800s, Macaulay had begun to veer from his profession into activism. He became a lone voice against colonial policies on land, water, and what he felt was non-judicial use of public funds. A member of the Anti-Slavery Aborigines’ Protection Society, for most of his life, Macaulay was a staunch opponent of white rule. When the British claimed they were governing with “the true interests of the natives at heart”, just like our governments claim today, Macaulay rejoindered this claim by writing that, “the dimensions of ‘the true interests of the natives at heart’ are algebraically equal to the length, breadth and depth of the Whiteman’s pocket.”

In 1908, when the belief was that Europeans were salvationists on rescue, Macaulay exposed them as filthily corrupt in their handling of railway finances. In 1919, at the Privy Council in London, he stood in argument for native chiefs whose lands were grabbed by the colonial government, forcing them to pay the chiefs compensation. Writing in the Lagos Weekly Record of May 2, 1925, he attacked what he called Sir Hugh Clifford’s “fat salary” of £41, 833. 6.8. In 1928, Macaulay was convicted for sedition in his allegation that the colonial government wanted to assassinate Oba Eleko. He was consequently barred from elective office.

In order to bring him to book due to his trenchant opposition to government, Macaulay’s private survey and architect practice was used to allege fraud and criminal misappropriation of funds from an estate where he was engaged as an executor. The Mary Franklin Estate belonging to a deceased client of Macaulay’s, which he was managing, became an object of litigation. In 1913, he was tried by a Robert Irving, who was the prosecuting counsel in the case, for stealing 350 pounds and imprisoned for two years. Some historians claim Macaulay might have been a victim of vendetta. For all his fights for the people of Lagos, a song was composed in Macaulay’s honour which goes thus, “E ki Macaulay o, Oyinbo alawọ dudu” (Macaulay deserves reverence; this white man in black skin). Another Yoruba Sakara genre musician of the Lagos colony of the 1920s and 1930s, Abibu Oluwa, regarded as the first breakout start of that traditional musical genre music, recorded a track in his tribute where he sang, “Macaulay Macaulay, Ejòń’gboro”. Ejòń’gboro – Snake on the Street – was Macaulay’s alias.

Both Saro-Wiwa and Vatsa also personified the sacredness of the word. Apart from his environmental activism, Saro-Wiwa was a great writer whose works included television, drama and prose. As a young student of the University of Ibadan, he wrote the Transistor Radio, a play which, in 1985, he re-produced in Basil and Company as a screen adaption, and proceeded to write the Four Farcical Plays and Basi and Company: Four Television Plays. In 1985, Saro-Wiwa wrote Soza Boy, an account of the Biafran war, written in a hybrid of standard and pidgin English. Same goes for Major General Mamman Jiya Vatsa who was also an accomplished poet and writer.

I went on the above historical journey to situate the Tinubu administration’s perhaps unintended recognition of the sacredness of the word in the president’s last week pardon granted Macaulay, Saro-Wiwa and Vatsa. However, for the administration and a herd of its servile supporters, it is the proverbial favour of Esu Ẹlẹgbara, the devil. As Esu approbates, it reprobates. Like Esu, the benefit Tinubu gave with one hand, he and his social media lieutenants repossessed with the other a thousand times. Take for instance the television confrontation between Rufai Oseni of Arise TV and Minister of Works, Dave Umahi last week. In the obsession to demonize Rufai, those I label regime boot-lickers took away what looked like harvested gains by the Tinubu administration. By granting those patrons of the word pardon, even though some have said for political reasons, he invariably acknowledged the potency of their word-crusading.

Let us get some fundaments right. First, Rufai Oseni is one of Nigeria’s most brilliant journalists. I confess to being addicted to watching him. In my 30 years active romance with the word, seldom have I encountered someone in possession of such robustness of mind and an obsessive quest for the good of society. Anchoring his belief on Niyi Osundare’s credo that the word is powerful, omnipotent and omnipresent, the creation and the creator, Oseni uses words to be a guiding principle for those who want a good society.

Last Friday when the Norwegian Nobel committee, in far away Oslo, was announcing Maria Corina Machado as its 2025 Prize winner, my mind went to Oseni, his crusade for a just society and his travails in the hands of Nigerians who have grown luscious inside the sewers of bad governance. The Nobel committee said one of its requirements which Machado met, was “promoting democratic rights for the people of Venezuela and for her struggle to achieve a just and peaceful transition from dictatorship to democracy”. Permit me to state that, substitute Venezuela for Nigeria and the committee could as well have been referring to Rufai Oseni. In his small corner of television advocacy and activism, Oseni, like Machado, challenges monarchical rule dressed in the garb of democracy. He has tirelessly advocated for free elections and representative government. If you read the work of two scholars, Olakunle A. Lawal and Oluwasegun M. Jimo, in their journal article entitled “Missiles from ‘Kirsten Hall’: Herbert Macaulay versus Hugh Clifford, 1922 – 1931” as I did, you would see in Rufai Oseni the Herbert Macaulay spirit.

A motley crowd palace courtiers denigrate Rufai Oseni today for rousing us all against a brand of civilian colonialists, the type Macaulay fought to a standstill. Like Macaulay, Oseni faces intense persecution. Macaulay’s is mostly from Lagos people and the colonial government whose perception of him was that he was an unnecessary pest. Many think same of Oseni, too. If Macaulay had been an anchor on TV as Oseni is, the Tinubu government Rottweilers would have bayed for his blood, too. During Macaulay’s court trial, a local musician called Gbadamosi Bishi composed a song for him which approximates the high level of opposition against colonial rule of the time. The lyrics went thus: “E wo ore e se. Ànfààní ayé s’eńkàràbà. Ẹ ò rí Macaulay t’ófé kí ayé ó ye wá, Èkó parapò wón gbé yen lu ìyonu Ọba”. Its translation, in the words of Lawal and Jimo, goes thus, “Please, be mindful of the good turns you render to people. The good of this world is fast disappearing! Look at Macaulay who is trying to make life easy for all of us. Look at the way the people of Lagos have conspired to get him into trouble with the Imperial government!”.

What many do not know is that, what Rufai Oseni and his very few fellow travelers on this rarely-traveled road go through in fighting bad governance and entrenched forces of democratic retrogression is significant. You may deplore his method of fighting the self-serving and the “violent machinery of the state”, but you cannot undermine the fact that Oseni is, just like Machado, a “symbol of (our) collective aspiration against an alien government that (doesn’t care for our) welfare.”

The Nobel committee had strong words for those who perceive criticism of the government as adversarial. In a country where hero-worship and the belly, rather than principle, dictate the compass of individuals’ stands in the blight of normalcy currently reigning in Nigeria, the word, as represented by the media, plays crucial role as representatives of free speech. The Rufai kind who hold governments accountable is fast becoming extinct. When a Minister of Works appears vague and opaque on the cost of roads under his superintendence on national television, it is the responsibility of a journalist to make the minister lose his appetite. That was what Rufai did. You may not like how he did it but that is business for further discourse. That he courageously did it, without cow-towing to his dollars and grits, Oseni deserves our own Nobel. Erstwhile clan members with whom the likes of Rufai ingressed and egressed through the same àgánrándì (a traditional Yoruba door) have recently almost all exited, citing their love for country and how “hate and anger should not blind Nigerians to progress.” The Rufais should be commended for not following the ignominious paths of our brothers, Judas.

Come to think of it, what Rufai demanded was just accountability. If a government awards a Lagos-Calabar Coastal Highway, a 700 km project, for $11–13 billion (₦15.6 trillion) to the self-confessed friend of the president, where his son is a director, methinks this incongruity should raise red flag in the minds of any righteousness-seeking nation. If, however, you have chosen to live a fawning life of grovelling before your Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves over this matter, why demonize those who are asking questions? Even the governor of Oyo State, Engr Seyi Makinde, an engineer like Dave Umahi, has imputed that his ministerial grandiloquence has no place in accountability So, why was Umahi waffling on the cost of the road per kilometre?

We are not all Lagosians who don’t ask questions. Lagos has never asked a single question about the running of its state since 1999. But that is Lagosians’ own problem. What Rufai Oseni and some of us are saying is that, in reality, we are not advocating that the Àgàtú should not chant the Yoruba traditional oral praise poetry called Rárà. Rárà is chanted at ceremonies and used as salute in praise of an individual. What we however deplore is the Àgàtú chanting the praise song of our mother – “Aà ní kí Àgàtú má sun rárà; k’ó sáa má fi ki ìyá wa”. This fear is raised because Àgàtú, a Benue State tribe, many of whom lived in the Southwest, were renowned for their predilection for mis-pronunciation while mimicking Yoruba words. In other words, those obsequious fawners of power should not extend their canopy of silence to our side.

As I was rounding off this piece, I saw Umahi’s reply to the Oyo State governor’s call for him to stop making cost of road per kilometer rocket science. In his reply, Umahi denigrated the engineering profession with a vain boast that his own field of engineering was “senior” and another section of the profession was subservient to it. I leave engineers to reply to this. However, as I was wondering what brand of small-minded people are at the helm of affairs in Nigeria, I read a fellow engineer’s reply to Umahi’s assertion which makes the minister appear to possess a very little mind. The engineer said, with his position on cost of road per kilometer, Umahi was talking bunkum. This is because, he said, even in first year in the university, an engineering student, regardless of field, is taught Engineering Accounting, BEME and BOQ as general engineering courses. COREN even takes all prospective engineers through this basic knowledge.

I knew Umahi’s god, in the words of Oscar Wilde, “dwells in temples made with hands” but I never knew he was this vacuous and petty. After all said and done, the Minister will still need to answer the question Nigerians pose to him: how much does that road cost per kilometer? After all, Yoruba say, a walk is presumed to be straight, (san-an laa rin) except financial cunning is involved (aje ni mu ni pẹ kọrọ). They also say that, except one who spreads a perishable commodity in the open, no one else is expected to fear a downpour (Bi eeyan o sabọti, kii bẹru ojo). Minister Professor, please provide the answer.

The truth is, words are what despots and pretentious lovers of democracy first seek to hold captive. Yet, the word is the most valuable hand-tool of democracy. The choice is, however, ours: We can continue to demonize the Rufai Osenis and idolize individuals who fawn before regimes, the palace appeasers, courtiers, and regime sympathizers like Reno Omokri, Daniel Bwala and their clan. As I told one of them on a Whatsapp platform last week, we will all someday reap the fruits of where we stand.