Biafra took a plum place at a recent literary fest known as the Quramo Book Festival that holds annually in Lagos. I was a member of a panel that also starred writer Professor Dul Johnson, film maker Emeka Ed Keazor, soldier and writer General Akintunde Akinkunmi, host of books on Channels Television Kunle Kasunmu, who also laid the context for the parley.

Novelist Tade Ipadeola held the time, pulse and tempo as moderator.

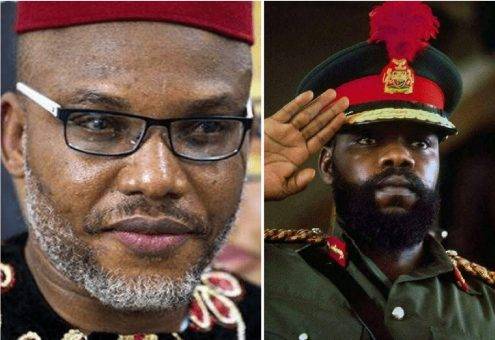

The title, a mouthful, was “961 Days, Brothers at War. Never again…” I spent quite some time reflecting on the points and narratives of the panelists, and the first is the topic’s relevance today, even as top men in the east are asking for Nnamdi Kanu’s release even though he has not renounced Biafra.

They guarantee his good behaviour when he has not even made any such pledge. They want the president to upend the rule of law by setting him free.

The other side of the story is the subliminal rage on the streets and even among the Igbo intelligentsia, a temperament not yet canalized or defined in public. Sometimes it is a boiling kettle without a whistle.

Two things the other panelists said cut me to the quick.

Filmmaker Keazor recalled an incident with his mother who was seized by a moment of distemper and slapped her son for no reason.

It was an onset of PTSD, a reflex of war trauma. The other was by Professor Johnson, whose life changed when only one of his three brothers returned from the war.

There is no superior tragedy but his case had the dubious mercy of numbers compared to the Second World War yarn of the Ryan family documented in the movie, Saving Private Ryan. Three brothers were already killed. War General Dwight Eisenhower ordered that the lone surviving brother must be saved.

There were two issues for me as I reflected after the fete of ideas. One was ego. I asserted that the war was not necessary, and only ego precipitated it.

I said the actors were about 30 years of age, and their immaturities provoked the slaughter of innocents. Ojukwu and Gowon were about 30 years old, and the nation’s future lay in their callow hands.

Ego set in because Ojukwu said he could not serve under Gowon as his Supreme Commander. General Akintunde, who wrote a book on the Nigerian army titled: Hubris, titillated the audience by tracking the careers of Gowon and Ojukwu, and how in alternating episodes each was the other’s superior until they both were promoted lieutenant colonel the same day.

So, after Ironsi’s death, Gowon was made head of state having served as Ironsi’s chief of staff. Ojukwu would none of it.

This happened in two contexts. One, the pogrom in the north that targeted Igbos especially but lapped up other southern groups including Efik, Ibibios, Urhobos, Itsekiris, etc, a point that drove me to work the minority angle in my novel, My Name is Okoro.

Here again, we witnessed the error of age. The countercoup leader, Murtala Muhammed and his colleagues, shunned an important opportunity for peace.

They could have accepted Brigadier Babafemi Ogundipe, the most senior army officer, as the head of state. If they did, they could have avoided the pogrom in the north, the battle between Ojukwu and Gowon and the civil war.

It was Murtala’s erratic folly and his lack of political intelligence, including his advisers, that led to Nigeria’s tragic moment.

Even then, when the pogrom happened, Ojukwu might have averted the war for a number of reasons. One, the prospective economy did not have the resources to win the war.

The most important asset in a war is not a mere will, important as it is. Napoleon said, “Morale is to the physical as three is to one.” But the morale must be fed by a good economy. The same Napoleon asserted that “an army marches on its stomach.”

Ojukwu and his advisers did not reckon on the stomach. Before the war, the eastern region relied on food, including fish and meat from outside.

How do you start a war without a food economy? Hence, the soldiers kept raiding markets in the Midwest for food and sustenance.

The Awolowo currency change and the food blockade worked because Biafra relied on food from outside. If its economy was able to produce its own food, then its currency would have worked for itself in spite of federal devastations.

On the economy, Ojukwu made a gamble. He signed a deal with the Rothschild Bank of France guaranteeing sole exploration of oil wells he had not secured. It brought France into the Biafran side but too late indeed to change its fortunes.

There are so many reasons for victory in war. But hubris, over the centuries, has played a role. Hence Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote that, ‘’in analysing history, do not be too profound for often the causes are quite superficial.” Because of its weak economy, it could not equal the federal side in the acquisition of arms. Yet, having declared Biafra, he did not stay home. His soldier marched onto the Midwest and headed towards Lagos.

A dissipation of scarce resources. Reminds one of Hitler’s “Operation Barbarossa.” Why did Ojukwu do so? His heart was still Nigerian, if he didn’t know it.

He wanted to be part of a country he was renouncing. Hence, when he died, I called him Omo Eko. He wanted to teach Gowon, who he called Jack, a lesson.

That was hubris. He was in two binds. One, he could not feed his people without going out. He could not teach Gowon a lesson without conquering Lagos.

He succeeded in neither. Biafra became a lost cause. Ojukwu spoke Yoruba, attended King’s College, lived in Lagos and blended with its metropolitan elan.

So, If Murtala and his advisers did not make Ogundipe the head of state, Gowon did not seem to want a war. So, he declared a police state, and we had for some time what historians called a phony war in the beginnings of the Second World War tensions of soldiers without conflict.

In Soyinka’s memoir, You Must Set Forth At Dawn, he recalls a meeting between Awolowo and Ojukwu to avert the war. But after a long talk ended, Ojukwu took, later that night, one of his associates to Awo’s chalet and told him he and his people had decided on war. He respected Awo too much to waste his time. Awo could not dissuade him.

If Ojukwu walked to his people and said, “no war,” Christopher Okigbo had allegedly said even market women would stone him on the streets. He might have saved millions of lives, including Okigbo and, on the federal side, Adaka Boro. Winston Churchill misquoted: “It is better to jaw jaw than to war war.” The wartime leader actually said, “it is better to meet jaw to jaw than war.”

Maybe Ojukwu relied on his officers. The Igbo had the better officers in the country, pound for pound. But in war, as in sports, one ingredient does not guarantee victory. Alexander Madiebo explained in his war memoirs that they did not have the armory.

The war, in the final analysis, reflected the interdependence of the east with the rest of the country, and that was why Quramo fittingly titled the discussion, Brothers at War

In spite of all these, the bitterness of Biafra creeps into any narrative of our oneness as a people. Is it because we have never had a real jaw-to-jaw confab or the jaw does not touch the mutual hearts? The answer to a slaughter is not another slaughter.

The answer to the pogrom was not another one in the name of a civil war.

In the United States, Donald Trump embodies the rebirth of American civil war malice fought in the 19th century. As novelist Viet Nguyen wrote, “A war is fought twice. One on the battlefields and the second in the mind.”

It is better in the mind than on the battlefield, so long as it does not spill blood. We must learn not to have men not old enough for authority, who cannot distinguish between power and strength. The crisis of the 1960’s prospered on the hubris of politicians, especially in the Western Region.

It is remarkable, as former inspector general of police M.D. Yusufu reveals in a biography written by Ayo Opadokun, that the Northern Peoples Congress (NPC) had opted out of the deal with Akintola and his NNDP. Northern leaders Kashim Imam and the Sardauna Ahmadu Bello told the colourful premier they did not want to be the source of his fight with his kinsmen anymore.Just a day before the January 15, 1966 coup when he was killed.

Yusuf’s said he was a witness to the conversation with Akintola.

What if the decision came two days or three before the coup?

We might muse on what might have been, but we cannot but ponder on why Nigeria keeps going back to its problems as though we have not gone past them.

Philosopher Nietzsche calls it “eternal return.” We keep exhuming our ill-tempered ghosts, just like in the line from the Poet Afred Lord Tennyson: “ O me…why have they not buried me deep enough?”