For 23-year-old Basit Badmos, what began as a quiet and enjoyable life in Mushin, looking after his aging grandmother and learning civil engineering, quickly turned into a horrifying spiral of fear, violence, and survival.

In February 2025, a deadly clash between rival cult groups, the Aiye and Eiye confraternities, erupted in Mushin, Lagos. Though these gang-related fights had previously seemed distant, the violence eventually reached Olufunmilayo Street, Basit’s neighborhood.

“It was a bad experience,” Badmos recounted in a trembling voice.

“The trauma is unbearable. I was only looking for something to eat that night when I saw people running. I ran too.”

From a hiding place, Badmos witnessed a chilling scene, a known resident involved in the cult clashes and the fatal shooting of one of the cultists, believed to be a member of one of the groups. That single moment would come to haunt him.

Moved by a civic sense of duty, Badmos shared his eyewitness account with security agents patrolling the neighborhood the following day, an act that would later endanger his life and force his family into hiding.

Weeks later, while on a work trip to Osogbo, Badmos received a distressing phone call from his father that unidentified men had come looking for him. According to his father, the men threatened to kill the entire family unless he (Badmos) joined their cult because they learnt that he gave the police information about them.

“They wanted to force me into their group and also add my father to the list of those supporting them because he’s a strong politician,” Badmos said.

“That’s when I knew my life was in danger. I changed my number immediately and went into hiding.”

A friend later confirmed that the same group had been trying to track him down, possibly using an old phone number. “That’s how I knew they were serious. I had to disappear,” he added.

In April, Badmos secretly returned to Lagos to meet his father and discuss next steps. But danger found him again. Just minutes after alighting from a bus in Isolo, two men approached him, ordered him into a car, and abducted him.

“They told me to cooperate if I wanted to live. I thought I was going to die,” Badmos said.

He was taken to an unknown location, stripped, beaten, photographed naked, and used to extort money from his father. Fortunately, community security officials tipped off by his father combed the hideout and rescued him.

“The only thing that gives me peace is that, even though it cost me everything, my information helped stop these criminals from hurting more people,” Badmos said.

Badmos explained that he now lives in an undisclosed location. Only his father has his new contact details, and the rest of the family has also fled their Mushin home due to continued threats.

“Every time I hear the names Aiye or Eiye, I can’t eat. I can’t sleep. I wonder how did they know my movements? How was I found so easily?”

Now, free from immediate danger, Badmos reflects on his experience with a mix of pain and pride. “This life is deep. I’ve learned that safety is everything. I hope one day I can truly be free from this trauma.”

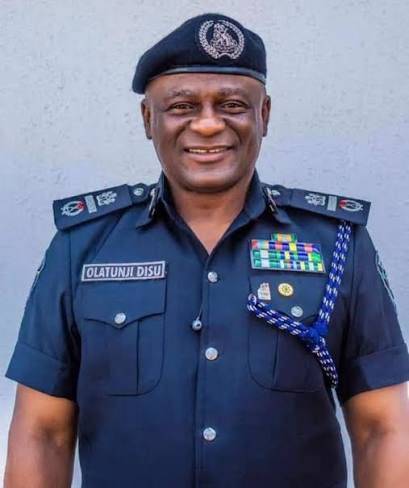

Badmos’s heartbreaking story and the undesirable frequent cult clash in Mushin, did not only catch the attention of this medium, it has spurred the house of assembly member representing Mushin Constituency II, Hon. Olayinka Kazeem, as well the legislative chamber as an entity to summon the State Commissioner of Police, Jimoh Moshood, the Commissioner for Local Government and Chieftaincy Affairs, Bolaji Robert; the Commissioner for Budget and Economic Planning, Ope George; and the Commissioner for Education, Tolani Ali-Balogun for questioning over the loss of innocent lives in the community.