By Anote Ajeluorou

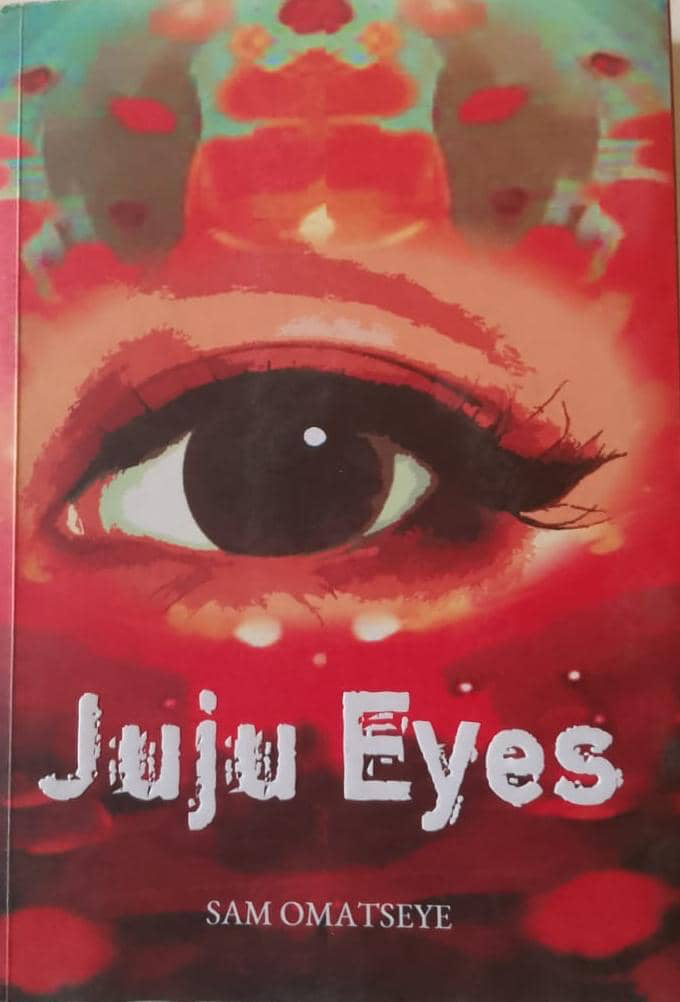

CROCODILE Girl is Sam Omatseye’s first novel published in 2011. It chronicles the lives of a stigmatised local girl deemed by her community to be of weird parentage, and a foreigner, a white man, out to discover his roots in Africa in the forgotten past steeped in inhuman practices, with the lives of these two disparate characters intersecting at the junction of a community’s unraveling. Fourteen years later, Omatseye is back with Juju Eyes (Sunshot Associates, Lagos; 2024), another haunting story of racial significance with a lilt, but also rooted in the lives of a local girl and a foreigner, another white man, with their lineages playing significant roles in who they become. The local girl Oluseyi (who transforms to Shay to reflect the new persona she morphs into) has an ancestral pact with her village goddess, the goddess’s gift of inexorable beauty becoming at once a curse and a blessing. But she inadvertently sets her goddess and shrine ablaze after initiation as a priestess at four, and symbolically becomes the goddess’s incomparable incarnate, but with consequences that trail her all her life.

She loses her father at an early age and her Uncle ID takes her into his care, but this turns out badly. But as Shay’s beauty unfurls as a teenager and when she enters the university, Uncle ID cannot take his eyes off his niece until incest inevitably happens to their collective mortification. This unfortunate family scandal would set Shay on a path that takes her from her life as an innocent girl to a worldly-wise one where she conquers the rich and the powerful. She’s emboldened to enter her university beauty contest after her fall from innocence, and comfortably wins the crown. This opens doors to a life of debauchery, fame and wealth, as her body becomes the playground of the rich and power in society.

Shay’s heated confession and confrontation with her boyfriend Osa sums up the trajectory of her acquired lifestyle, that of a fallen angel groping her way around, with debauchery defining many a beautiful young girls’ lives in fast, furious and shinny cities across Nigeria: ‘Look, you think I am miss clean? I have a surprise for you. I am not what you think. I am a runs girl. I have men, and they have me whenever I want them to. My body is not as holy as you think.’

The narrative intervention or commentary of that particular scene is sobering and staggering: ‘…she said those words with hysteria, almost screaming her every word at him. But when she saw that Osa was quiet and absorbing her every word with attention and consternation, she grasped the weight of her revelation. Her voice became calm, even equable. She was also a little more peaceful.’

While Shay’s debauched life of service to the rich and powerful men in society unfolds, Omatseye also cleverly uses her as a touchstone to interrogate certain socially troubling issues, culturally unsettling practices and politically sickening norms. In her forays as the incomparable beauty and dalliance with men, Shay also sells high class fashion materials on the side, with broadcasting on radio as her regular job. She meets a woman she would adopt as godmother – Madam Lola. A wealthy and high society woman, Madam Lola is as a good a fraud as they come. Through cunning and patronage of a baby factory, she is ‘delivered’ of two sets of twins to cover up her barrenness, and so deceives her husband. But when the couple who run the baby factory hit their own jackpot and decides to have their children back, Madam Lola’s world comes crumbling down, and exposes an unenviable side of the world of the rich who do everything underhand stuffs just to keep the facade of gentility.

Shay’s boyfriend Osa has his own wildly consternating drama as a politician and ensnarer of young, innocent girls whom poverty thrusts into a rudely unsettling world that politicians like him made crooked and wrongly wired to their disadvantage. A Youth Corps member Beatrice falls into the snare of Osa’s charms, and they hit if off. But things soon turn awry as Beatrice dies while pregnant. Osa is fingered as the culprit. Her Luka society cannot bury an unwed woman who died while pregnant; Osa must marry her before she is buried otherwise the gods go on rampage on the head of the erring partner. To save his political career, Osa must marry the dead beatrice. The Luka marriage tradition to the dead happens in some Nigeria communities. When Osa is made to make out with the virgin bride who stands in for Beatrice, the reader’s sensibility would but be riled to such extent that the validity of that tradition must come under scrutiny. What is more disconcerting is when it comes t light that Beatrice was already symbolically wedded to a man from a community where the snake totem plays a role in cementing the married union. The unborn child takes the place of Osa as victim of the totem’s wrath!

Also on the political turf, Osa is a fringe player even if he’s in the thick of his party’s commanding height as secretary. Chief Lambe asks him to make a bonfire of his hard earned money in millions of naira, so he can gain his support for a senatorial district ambition in his Edo home state. Omatseye cleverly avoids the blood rituals politicians allegedly carry out for such high stake political favours, but opts to ritually have Osa’s money burnt instead as sacrifice. This somewhat lessens the scandal of such act and avoids the usually prevalent Nollywood’s uncritical, unnuanced artistic portrayals. Does Osa gain the expected favour of Chief Lambe for his political ambition for which N3 million goes up in flames and smoke? Osa and Chief Lambe’s cat and mouse merry-go-round is a perfect study in Nigeria’s tricky political nuances and human perfidy.

Having tired herself out with the philandering men in her life and after dumping Osa, Shay happens on a rich British oil worker Nigel, who calls himself Mista Naija on account of his love for everything Nigerian and local, from food to music, particularly Fela’s Afrobeat that he waxes dexterously to with his saxophone. But like Mr. Forester of Crocodile Girl, Nigel has a past rooted in colonial Nigeria and the tragic incident in Enugu, the massacre of coal miners at Iva Valley on November 18, 1949. Nigel wants to make some sort of atonement with the offer of scholarships to deserving Nigerian university students, particularly at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, but this produces its own backlash with some students protesting the gesture. Alongside Shay, Nigel manages to pull off the scholarship award with the help of virtual assistance…

As a cultural historian, Omatseye reminds his readers about the Enugu Colliery Massacre of 1949 in Juju Eyes, as part of the restitution clamour for the many wrongs Europe dealt Nigerians and Africans during colonial rule.

Nigel’s grandfather, a certain British Superintendent F.S. Philips, ordered the shooting of coal miners who were protesting unpaid wages. Like Shay candidly admits, many Nigerians are not aware of this piece of tragic history and several others like it perpetrated by the colonialists. But Omatseye brings attention to it as a deliberate historical reminder even if in a fictional work. When Nigel is captured by the agitators in the Niger Delta, there’s abundance of sympathy for him, especially with his girlfriend Shay protesting nude alongside other women for better conditions for the people of the oil-rich region. But on learning about this historical truth, feelings about Nigel become somewhat ambivalent, especially when he disrespects Shay before his colleagues in the US.

Of course, Nigel’s brush with Niger Delta militants and the days he spends in their den as hostage make up part of the sociological sweep of the novel as a chronicle of a ruptured society in need of urgent mending.

Juju Eyes is a novel characterised by ‘what ifs’. What if things had happened differently, what should it have been? What if Shay’s Uncle ID didn’t rape her, would she have been contented with her university boyfriend Ese and live happily ever after? What if she had not burned down the goddess’s shrine, what would her life have been as a priestess? What if her dad had not died in an accident, what trajectory would her life have taken? And what about Nigel or Mista Naija? Would he have come into the fray as Shay’s husband if things had happened a bit differently? Omatseye’s narrative commentary lends credence to the what-might-have-been sub-theme that plagues many a parent today across Nigeria where values have been upended on account of filthy wealth that people acquire with no known legitimate means:

‘She had seen her daughter visit and show affluence without ostentation. She had not asked questions. She just let her be. She was grateful for her mother. She was also sad. She resented Maami for not berating her. She had let her to her own devices since she fell from virginal grace, since Uncle ID preyed on her…, but she wanted Maami to know that if Uncle ID had been true to his role as watchman over his niece, Shay would not have been born. Oluseyi would have married a certain fellow called Ese. Ese was a man who would remain a phantom lover. She was paying for what might have been. She was paying because Shay failed but also because Maami relinquished her maternal vigilance.’

In a bold way Omatseye has, through the sweeping lens of Juju Eyes, painted an alternative social consciousness: what might have been but for certain choices made at the witching hour things went horribly wrong with society, with individuals, and the result is the stark reality of badly managed society starring everyone in the face. Indeed, what comes through is the need to carve a different, better path for a society gone awry. From Shay to her protege Bimbo, Omatseye chastises society for letting her vulnerable members to be preyed on by those who have wrongly wired society such that it doesn’t work well for all, but a select few who pour filth in society’s face for being negligent in its duty of calling everyone to order and good behaviour. Society becomes Maami, a negligent parent who looks on while the children misbehave, yet somehow expecting them to turn out to be models.

Omatseye’s Juju Eyes is a vast, sweeping, epic narrative that undercovers the underbelly of society in unflattering manner. Although it starts slowly and ungainly in parts, but when the narrative finally gathers momentum it sweeps along like a tidal wave, upending the flotsam and jetsam of society for what they truly are – a plague. It’s a rewarding read.