By Palladium

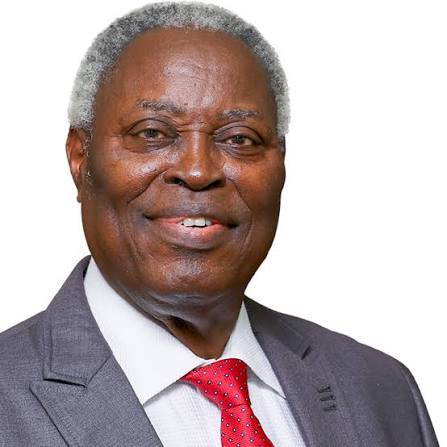

By now, nearly everyone knows that the person of former president Olusegun Obasanjo cannot be changed by abuse or by any form of unwholesome exposure of what he has done or not done, in the past, present or even future. He is set in his ways, and this old man, as they say, is not for turning. In far away United States, at a Chinua Achebe Leadership Forum lecture he delivered at Yale University in Connecticut, he was at his didactic and sermonising best. His recorded lecture, which spoke more to the Obidient worldview than anything else, was provocatively titled Leadership failure and state capture. He needed no other baiting to be at his pontifical worst. After many decades of the former president serially and periodically pontificating on the same narrow subject, Nigerians should be used to his style and methods. Whatever he says about any issue, whether diagnostic or prognostic, has absolutely nothing to do with whatever he does. Academics love to talk about praxis, the execution of ideas. Chief Obasanjo has no interest whatsoever in any such convergence; indeed he has contempt for bridging any divide. Whoever wants to take the former president to task should simply concentrate on what he says rather than the chasm between what he says and does.

He supposedly spoke on leadership failure and state capture, but much of what he said was frustratingly platitudinous. Apart from saturating his text with authorial references, and undergirding the address with unashamedly narcissistic comments, it is not clear whether his audience did not labour to wade through his quotations to find one pearl or gem worthy of the subject matter. The topic was grand and engaging, even though distinctly Obidient; but unfortunately, Chief Obasanjo lacked the depth of understanding and rich background to explicate the subject. Forget about his person or his style as military head of state and elected president, his treatment of leadership failure was simply far too superficial to attribute to anyone who had ruled Nigeria for a cumulative period of about 11 years, the longest of any past Nigerian ruler. His ideas on leadership have not changed one jot for the better over the years; instead they have worsened, aggravated by comparisons with his successors and predecessors, and weakened by a stubborn refusal to be introspective or learn from past great leaders. Unable to really diagnose the problem, he quickly transitioned to his suggested remedies. But here too he fell on his sword.

Perhaps his instincts tell him what his audience wanted to hear, and he was not one loth to serve them the menu they craved. To tackle leadership failure, the first thing he recommended was strengthening democracy, without resolving the conundrum of which comes first, the chicken or the egg. His previous analyses of democracy ended in his suggestion that Nigeria should develop a homegrown democratic model, again without elucidating on both its rubric. So, how does a country strengthen a democracy it does not know? And, worse, how does a country tinker with or restructure a democracy whose model it has not settled on? And if homegrown, what are its component parts and its anchors? The French Fifth Republic, the American 1789 constitution, the Chinese reforms begun after the death of Mao Zedong and the castration of the Gang of Four? At Yale, Chief Obasanjo did not structure his ideas, but merely clamoured against the 2023 elections for being a ‘travesty by all rational measures’. He allowed his private longings and sanctimonious disregard for facts to get in the way. He equated his unfulfilled but visceral preference for Peter Obi’s Labour Party (LP) candidacy with the weakening of democracy.

Quoting the Pew Research Center, The Carnegie Foundation, and the Electoral Knowledge Network, he identified three planks upon which to strengthen democracy, to wit, legal, administrative, and political. Flowing from these planks, he advocated the wholesale dismantling of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), insisting that the agency was the fulcrum of democracy. To achieve this radical goal, he offered nothing substantial or rigorous other than the trite counsel about finding men and women of integrity. Had he been consistent with his homegrown democracy idea, which he nevertheless failed to concretise, he would have achieved a little bit of profundity and contributed to knowledge. It was clear he blamed INEC for the loss of his dear candidate, Mr Obi, but offered no rational or legal basis for coming to that unguarded conclusion. How he expected a largely unphilosophical, regional and religiously divisive party to win the last presidential election is extremely difficult to understand. And for a man who had ruled Nigeria for so long, he was shockingly unable to appreciate the legal reasoning that validated the disputed February 2023 poll. Indeed, moments later in his keynote address, he was to excoriate the judiciary for his unfulfilled dreams.

On the subhead of ‘rebuilding the judiciary’, Chief Obasanjo was withering, theoretical and even facetious.

“The Judiciary in Nigeria is a very pale version of its once internationally esteemed self,” he began magisterially. “Politicians after rigging elections openly ask their rivals to ‘go to court’ in Nigeria because they are aware that they have completely compromised the Judiciary system. A number of Judges are in the pockets of wealthy politicians and individuals and make judgements – not based on the law of the land but to the highest bidder. This, my learned audience, is one of the most effective strategies of State Capture – discussed next – that must be excised from Nigeria like a surgeon cutting out a malignant cancer.” His pet LP, not to say the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP), his former political party which he disassembled by his undisciplined approach to politics and governance, won some cases in court. But as long as his preferred party and candidate lost the grand prize, and regardless of the logic of the justices, the judiciary was hopeless.

He rounded up his lecture with a short dissertation on state capture, but managed paradoxically to make his analysis sound like his governing manual during his three terms in office. He could of course not resist a kick to the groin of his old nemesis, President Bola Tinubu, whom he described as the quintessential proponent of state capture; but by personalising and vulgarising his analysis, he undermined the integrity of his address, reflected the poverty of his worldview, was condescending to his audience, and ended up playing almost entirely to the gallery. Mercifully he did not travel in person to Yale. It would have been a sheer waste of money and time to have had to travel over such a huge distance to deliver an unglamorous and commonplace address.

Culled from The Nation