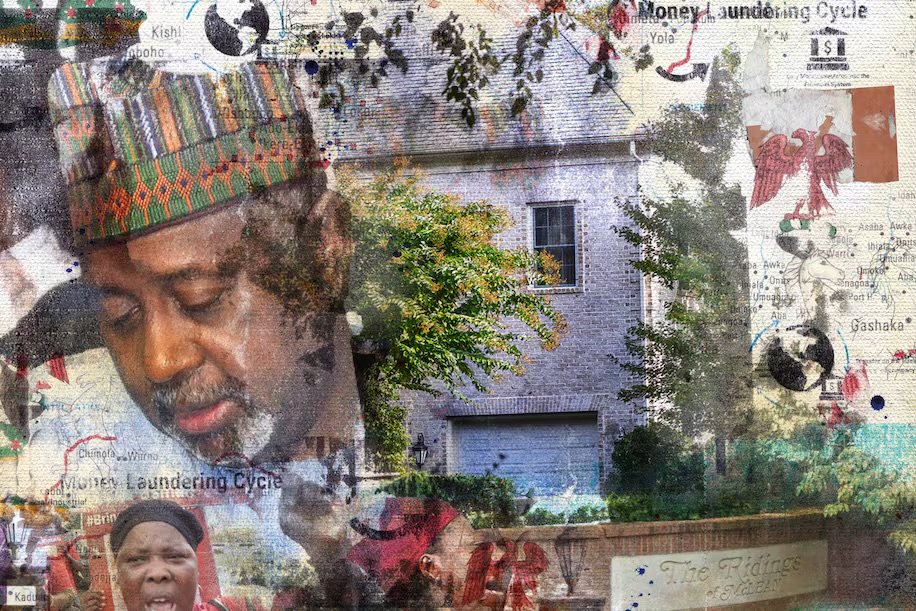

The $2.8 million mansion, tucked at the end of a private drive, boasts a climate-controlled wine cellar, sauna and four fireplaces — features not uncommon to this wealthy part of the Washington suburbs.

But the man who bought the place a couple of years ago did not stick around to enjoy them, neighbors said. He introduced himself, then disappeared, leaving some wondering what was happening behind his nine-foot-tall carved-wood front doors.

The mansions in leafy McLean, Virginia, like mansions everywhere, tend to hold interesting characters with money. Here along a quiet street in a neighborhood called The Ridings, there’s a noted plastic surgeon, a high-powered corporate lawyer and the CEO of a defense consulting firm, among others, property records show.

But court filings in Nigeria, as well as those from an insurance claim surrounding a jewelry theft from another mansion near Beverly Hills, California, suggest the owner of the McLean residence has a different type of story.

Story continues below advertisement

The way Nigerian authorities tell it, their country’s former national security adviser misappropriated more than $2 billion from his own government, routing some of it to a family friend — the man who bought the mansion in McLean. In the United States, according to Nigerian authorities, the man sought to launder the money in part by purchasing homes.

The allegations against him, experts say, underscore a significant global issue: The U.S. real estate market has become a money-laundering haven for corrupt officials and criminals across the world, a place to hide their cash behind opaque shell companies.

Next year, the U.S. Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network will begin receiving reports under a new rule requiring title companies and others to collect information about certain real estate sales — particularly transactions where the buyer is a trust or some other legal entity and pays with cash.

(Craig Hudson for The Washington Post)

“At a time when many American neighborhoods are experiencing affordable housing crises, it’s more important than ever to stop dirty money from being laundered and stored in our residential real estate market,” the Treasury Department’s acting undersecretary for terrorism and financial intelligence, Bradley T. Smith, said in a statement to The Washington Post.

For this story, a Paris-based anticorruption group, the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa, provided court documents, property records and analyses of them to The Post, as well as to the Premium Times, a Nigerian news organization, as part of a broader investigation into money laundering in real estate. The Post verified facts and obtained additional information independently.

A visitor to the quiet cul-de-sac in McLean would have no reason to suspect something amiss, even were they to venture along the private drive past two other high-end homes and knock on the mansion’s imposing front doors. The secluded lawn is freshly cut, the rosebushes neatly trimmed.

But behind its drawn curtains, Nigerian law enforcement officials allege, lies a tale of embezzlement, corruption and money laundered across the globe.

The Oshodins

On a sweltering night in 2014 in a town in northeastern Nigeria, men carrying AK-47s stormed into a boarding school and kidnapped 276 schoolgirls. The missing children became an international cause célèbre, sparking the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls that was used by, among others, Reese Witherspoon, Michelle Obama and Pope Francis.

The kidnapping brought global attention to the brutal tactics of Boko Haram, an insurgency that had tormented Nigerian society for years with a campaign to impose strict Islamic law. But the Nigerian government could not manage to find the girls. The country’s president, Goodluck Jonathan, was swept from power in the following year’s election and replaced by former military dictator Muhammadu Buhari, who pledged to defeat Boko Haram, as well as government corruption.

Under Buhari’s administration, Nigerian authorities turned their attention to the previous president’s national security adviser, Sambo Dasuki, accusing him of diverting large sums of money earmarked to fight Boko Haram. The new president ordered the arrests of Dasuki and others.

The money, Nigerian law enforcement officials said, trickled out to destinations around the world. One of the recipients, the officials alleged, was the man whose shell company bought the McLean mansion a couple of years ago. His name is Robert John Oshodin Sr.

Oshodin, 83, learned carpentry as a youth in Nigeria, according to his bio on an archived version of a website for a furniture manufacturing company he later founded, Bob Oshodin Organization Limited. Oshodin and Dasuki, who both lived in the United States for long stretches, became close friends after meeting decades ago, said Oshodin’s wife, Mimie Oshodin, during testimony in a civil case.

The families were close enough that the Oshodins agreed to look after two of Dasuki’s children, then teenagers, who were attending school in the United States while Dasuki served as Nigeria’s national security adviser.

It was also during this time, Nigerian officials alleged, that Dasuki illegally transferred tens of millions of dollars’ worth of Nigerian and U.S. currency from state funds to the Oshodins’ furniture company.

Dasuki was released on bail in 2019, re-arraigned in 2022 and has pleaded not guilty. A lawyer for Dasuki in Nigeria, Ahmed Raji, said he could not comment while his client’s case is pending.

Born into Nigerian royalty as the son of the sultan of Sokoto, Dasuki obtained degrees from American University and George Washington University in D.C. before ascending the ranks of the Nigerian military. After his 2015 arrest, Dasuki said in a statement that he was “not a thief or treasury looter as being portrayed” and that he’d acted “in the interest of the nation and with utmost fear of God,” the Premium Times of Nigeria reported. He also said he had “a lot to tell Nigerians,” a comment perceived by many as a threat to implicate other powerful Nigerian officials.

Robert Oshodin, reached by The Post at a phone number with a Los Angeles County area code, disconnected as a reporter described this article. He did not return a subsequent message.

Mimie Oshodin, 61, did not respond to an email requesting comment. A lawyer for her reached by phone in Nigeria, Osahon Idemudia, said he was bound by client confidentiality rules and could not comment.

A lawyer who represented the Oshodins in a U.S. insurance case, Alvin Pittman, briefly returned a phone call from The Post but did not provide comment. In a 2019 filing on their behalf, he noted that, in the years following the initial allegations, Nigerian law enforcement officials had “not produced a single conviction.”

The Nigerian agency behind the allegations against Dasuki and the Oshodins is the country’s premier anticorruption law enforcement authority, called the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission, or EFCC. The EFCC has scored prosecutorial wins over the years, while also weathering criticism for susceptibility to political influence and focusing on cybercrime at the expense of high-level corruption cases.

Its leaders have frequently been removed, and some have themselves been targets of misconduct allegations. These include Ibrahim Magu, who pursued the case against Dasuki but was suspended in 2020 and replaced the next year after the country’s attorney general accused him of corruption, allegations Magu denied.

In defending his record, Magu cited his office’s requests for the extradition of “high profile Nigerian fugitives” that included Robert Oshodin. The requests, Magu said in a response to a panel investigating the allegations, were hampered by inaction from the country’s attorney general — the man then accusing Magu of corruption. A court later cleared Magu of money-laundering charges, Nigerian news outlets reported. He did not respond to an email seeking comment.

The U.S. State Department’s former top expert in Nigeria, Matthew Page, said the EFCC’s leaders make powerful enemies and are vulnerable to shifting political winds.

“The reality of that job is that, as they say in Nigeria, when you fight corruption, corruption fights back,” said Page, who is now an associate fellow at the British think tank Chatham House and is advising the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa on its research. “When these guys sort of come out from under the umbrella of presidential protection, a lot of knives come out.”

The Los Angeles mansion

An indictment against Dasuki in Nigeria, obtained by the Premium Times, alleges that one of the transfers to Oshodin’s furniture company, of $12 million, was listed as payment for a “counter radicalization campaign.” A trail of evidence in U.S. and Nigerian court filings leads from that payment to the mansion in The Ridings in McLean.

The trail begins with bank records collected by Nigerian investigators, which show that in June 2014, days after receiving the money, the furniture company transferred $7.7 million of it to a bank in California. The Oshodins used it, Nigerian investigators have alleged, for the purchase of a $9.5 million mansion in Los Angeles.

The mansion, which sits in the Windsor Square neighborhood near Beverly Hills, is listed among LA’s historic cultural monuments.

Built in 1913 in a French neoclassical style, it was home during the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s to Norman and Dorothy Chandler, the influential owners of the Los Angeles Times. They called the home “Los Tiempos” — Spanish for “The Times” — and were frequent hosts of presidents, including Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon.

Features inside included “pillars in the living room brought from a Venetian palazzo, paneling in the formal dining room from a French chateau, and a large music room with hand-painted silk panels imported from Germany or Austria,” according to the city planning department’s 2006 recommendation to designate the home a historic site. Oshodin testified in a 2016 court case that the home also featured a 5,000-bottle wine collection, dozens of crystal chandeliers, $1.1 million draperies, and a “very beautiful door . . . from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart,” court records say.

About a year after the Oshodins bought the LA mansion through a shell company, they reported to their insurance company that thieves had broken into it, court records show. The Oshodins were in Africa at the time, but Dasuki’s college-age son and a friend were there. Robert Oshodin said during a deposition that Dasuki’s son said they had gone out. “On their way back, they opened the door, and found two guys” who told them to lie down, Oshodin testified. He said the robbers rolled two heavy safes from the Oshodins’ closet and out the door.

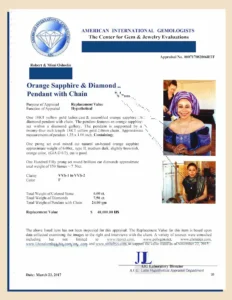

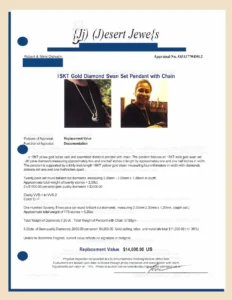

Oshodin said the safes contained $58 million worth of jewelry, according to a deposition taken by the insurance company’s lawyers, including a $2.6 million watch, a $950,000 ring, an 18-karat gold Vertu phone, and 10 or more diamond bracelets. An expert witness retained by Oshodin’s lawyer put the total value closer to $15 million. The insurance company, which said it was not informed of the jewelry when Oshodin bought the policy, offered $5,000 to cover the loss. The Oshodins sued.

Story continues below advertisement

The insurance company’s lawyers argued in response that because stolen money had paid for the home, the company had no obligation to cover the loss.

The Oshodins did not have an “insurable interest” in the home, an insurance company lawyer said in a 2020 court filing, “because they did not have lawful ownership of the house, having purchased it with illicit funds obtained from the Nigerian Government to which they were not entitled.”

In the end, the insurance company prevailed on different grounds, with a judge taking no position on whether the money was ill-gotten. But not before the company’s lawyers filled the case record in Los Angeles Superior Court with reams of bank records and other evidence of the funds’ origin.

The court records include an email obtained by the insurance company’s lawyers, sent by a Nigerian law enforcement official to the U.S. Justice Department in 2018. The email called Robert Oshodin a “suspect” who was “still at large” and added, “It is our humble request you track the money with a view to blocking it pls.”

The sender of the email, an EFCC official named Isyaku Sharu, did not respond to a message seeking comment. A spokesman for the EFCC, Dele Oyewale, also did not respond to messages.

The recipient of the email, Mary Butler, is chief of the international unit of the U.S. Justice Department’s Money Laundering and Asset Recovery Section. She referred questions to Justice Department spokespeople, who declined to comment.

The Justice Department can seek a court order allowing seizure of real estate bought with the proceeds of criminal activity, even without a conviction. Officials must establish “by a preponderance of evidence” that the money was ill-gotten, a standard of proof below the beyond-a-reasonable-doubt threshold for a guilty verdict. Still, it can be difficult to obtain evidence needed for such cases from a foreign government, said Karen Greenaway, a former FBI supervisor who focused on international corruption. “In some respect, the stars have to align in order for the Department of Justice to do a case,” she said.

The California court file also includes bank records related to the Oshodins’ purchase through a shell company of a $6.5 million mansion in McLean just as they were buying the LA home. The mansion, featuring an 18-seat home cinema, elevator and spa suite, sat at the end of a private lane just off Old Dominion Drive, a couple of miles from the one the Oshodins now own in The Ridings.

A bank log shows that Oshodin’s furniture company, soon after receiving the $12 million “counter radicalization campaign” payment from the Nigerian government, transferred $2 million to an account maintained by a Virginia-based title company involved in Oshodin’s purchase of the mansion off Old Dominion Drive. In a 2018 affidavit filed by Nigerian authorities seeking to seize the Oshodins’ properties, a Nigerian law enforcement officer alleged that both the mansion in LA and the one off Old Dominion Drive were bought with money misappropriated by Dasuki, in return for which Oshodin’s furniture company provided nothing.

In a deposition, Mimie Oshodin said she brought her jewelry collection on flights from Frankfurt, Germany, to LA after she and her husband bought the home there.

“You carry it bit by bit,” she told insurance lawyers.

She said she liked to use the home in McLean as a stopover on her way to Los Angeles, because long flights made her ill.

Mimie Oshodin agreed to another deposition with the insurance company’s lawyers in June 2019, given by teleconference from a Hilton hotel in Abuja, the Nigerian capital. About an hour into the questioning, the parties agreed to a short break. Before Oshodin could return, Nigerian law enforcement officials arrested her, according to court filings made by her lawyer in the insurance case.

That summer, Mimie Oshodin was arraigned in a Nigerian court on money-laundering charges. She and the furniture company were accused of receiving more than $57 million in national security funds diverted by Dasuki.

She has pleaded not guilty. When she was first approached by Nigerian law enforcement in 2016, she told investigators that the furniture company had agreed to sell its assets to the Nigerian government for $55 million several years earlier, according to a handwritten statement she gave the investigators. One of the company’s directors swore in a 2018 affidavit that a Nigerian government program had obtained the furniture company’s manufacturing plant as a place to conduct “de-radicalization and vocational training” for former militant youths. Also in 2018, a Nigerian news outlet described a tour of the plant by government officials, during which one was reported as saying the government was finally taking possession of the facility.

A Nigerian law enforcement investigator, in the affidavit in the property seizure case, disputed Mimie Oshodin’s account. A “false sales agreement” for the factory had been used in “a premeditated scheme” to launder money, the investigator alleged. There was no record of an actual sale of the factory, the affidavit said.

A Nigerian court released Oshodin on bail two months after her 2019 arrest. She was required to surrender her passport and report monthly to law enforcement officials. A trial was scheduled for that year, but it did not occur, and the case appears to have stalled. Robert Oshodin, who has spent much of his time in the United States, according to court records, appears to have remained out of reach of Nigerian law enforcement officials.

In 2022, a company that records show the Oshodins controlled, called 1812 Corporation, sold the mansion off Old Dominion Drive at a loss for $5.3 million. The same day, another company they controlled, called 1812 Investments, paid $2.8 million for the smaller mansion in The Ridings that the company still owns, according to property records.

The transactions amounted to a significant downsizing: from 20,000 square feet to a space nearly half that, and from the 18-seat home cinema to one with only six seats.

A new rule

In August, the U.S. Treasury Department finalized a new rule as part of a Biden administration effort to deter money laundering by requiring title companies and others involved in real estate closings to report information about cash transactions involving shell companies and other legal entities.

In recent years, the department has required the reporting of information — including the identities of people who benefit from transactions — in certain geographic areas.

Those places include Fairfax County, Virginia, and Los Angeles County, but the rules were not in place in 2014 when shell companies used cash to buy the mansions in Los Angeles and off Old Dominion Drive in McLean. The new rule will extend the requirement nationwide.

“The size, the relative stability and resilience, and the secrecy through which one can easily hide and launder illicit funds has made the U.S. real estate market a go-to investment for the world’s corrupt dictators, drug cartels, and U.S. adversaries,” Gary Kalman, executive director of Transparency International U.S., which had pushed for such regulations, said in a statement.

A decade after the notorious kidnapping by Boko Haram, more than 80 of the schoolgirls remain in captivity, according to Amnesty International and Nigerian news reports.

Hundreds more have been kidnapped since then as the Nigerian government continues to struggle in its fight against terrorist groups.

On a recent afternoon, the garage of the mansion in The Ridings was open, a black Lexus SUV parked inside. A man who serves as a caretaker for the home responded to a knock by a reporter on the front porch. Robert Oshodin was not there, the caretaker said. He declined to comment further, then pulled the heavy front door shut again.

Credit: Washington Post