By Segun Ayobolu

Once again, we are back to where we have all too often found ourselves in our developmental trajectory nearly six and half decades after the attainment of flag independence. I refer to the return of fuel scarcity, the resultant long queue of vehicles at fuel stations in towns and cities across the country with dire consequences for economic productivity, the inexplicable hide-and-seek game by the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPCL) on the root cause of the problem before its belated admittance of its humongous indebtedness to oil marketers and, again, another round of increase in the pump price of Premium Motor Spirit (PMS) signaling further negative implications for inflationary spirals. I have lost count of the number of times that the pump price of fuel has been raised since my youth as successive administrations purport to remove a seemingly never-ending subsidy attendant on the continuous exportation of crude oil with which the country is abundantly blessed and the importation of refined petroleum at humongous cost.

In the run up to the last presidential election, the major presidential candidates all pledged to remove the subsidy which one of them, Peter Obi, claimed he would do on day one if elected, describing the scheme as an elaborate scam. Yet, with President Bola Tinubu taking the decision on his inauguration on May 29, last year, to remove the subsidy, an unpopular policy option his predecessor had kicked down the line, his defeated opponents in the last election – Atiku Abubakar and Peter Obi- have opted to play politics with the issue grandstanding that they could have pursued a different path. In truth, the country had hardly any room for maneuver. A sinister and cynical cabal had seized on the inexcusable non-functioning of local refineries for decades to turn the importation of refined petroleum into an expansive criminal self-enrichment enterprise.

The option of the government continuing to bridge the gap between the combined associated costs of fuel importation and the relatively affordable price it was sold to consumers was unsustainable. The government had had to resort to incurring humongous debts in foreign loans to fund its operations with sizable amounts of dwindling total revenues dedicated to debt servicing.

But at the time President Tinubu announced the ‘final’ removal of the subsidy, the new administration was not totally in the picture as regards the sharp decline in volume of crude oil production due to industrial scale oil theft, the large amounts of crude oil that had been sold upfront in the futures market with the revenue collected and expended in advance and, of course, the deceptive illusion of expectations that the Port Harcourt refinery would be functional by April 2024 as repeatedly confidently affirmed by chief executives of the NNPCL. The new target date of the Port Harcourt refinery commencing local refining and sale of fuel was set for August and yet we are now in September and there is no indication of the pledge being redeemed anytime soon. Remarkably, the NNPCL celebrated its achieving what it considered to be an appreciable level of profitability in the last financial year only for its huge indebtedness to oil marketers responsible for the current acute scarcity of fuel across the country to be made public. Is this not a contradiction in terms – high profitability co-existing with humongous indebtedness?

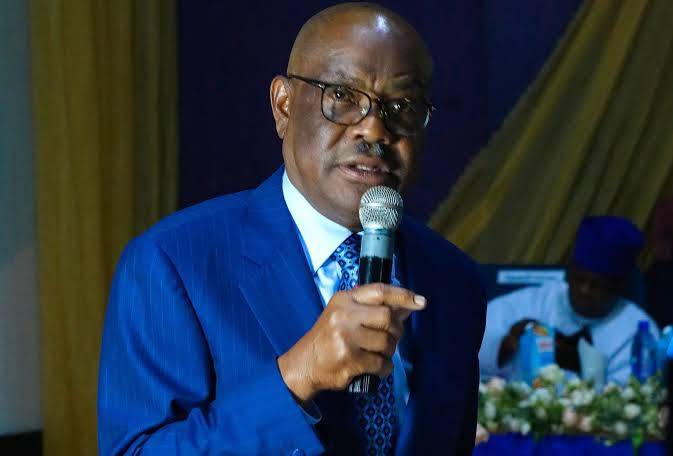

Only the mischievous and crassly partisan would blame the a little over one year in office Tinubu administration for the complications, challenges, and mostly self-inflicted woes of the petroleum industry and the associated sufferings inflicted on the Nigerian people as exemplified, for example, by the fresh fuel price increases. Yet, the administration must take it as a cardinal responsibility to undertake a surgical organizational procedure on the NNPCL to sanitize and reposition the company to offer productive service to the Nigerian people. The NNPCL should not be immune from the kind of forensic audit conducted on the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) in the aftermath of Godwin Emefiele’s reign of impunity for which he is currently facing the due process of law.

Despite the enactment of the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) and the purported transition of the oil behemoth into a private company, its operations and processes are widely believed to be as opaque as ever. Some experts contend, for instance, that the cost of producing a barrel of crude oil in Nigeria is the highest in the world. The controversial but knowledgeable Emir of Kano, Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, has publicly averred that the efforts of the Minister of Finance and Coordinating Minister of the Economy, Mr Wale Edun, and the CBN governor, Mr Olayemi Cardoso, cannot bear optimum fruit without a more transparent operation of the NNPCL and a more accurate data on the country’s crude oil sales and attendant revenues.

The quagmire in which our petroleum industry finds itself today was quite avoidable had the country’s leaders at various times listened to and worked more closely with Nigeria’s conscientious and patriotic progressive intellectuals. For instance, as far back as 12th February, 1971, the late Dr Bala Usman had, in a paper titled ‘Petroleum in the Economy of Nigeria’ had undertaken an incisive analysis of the problems and prospects of an industry so critical to the country’s development. As he put it then, “All the proposals and plans for post-war Nigeria are based on certain assumptions about our oil. From the government which, according to its Commissioner of Finance, expects a revenue of several hundred million, to the foreign businessmen licking their lips and assuring us of our rosy economic future, to the ordinary man and woman – oil has become a basis for optimism about the future. This widespread awareness of our wealth in oil is combined with gross ignorance about the operations of the petroleum industry and its international context.”

It is the unfortunate truth that ignorance about the operations of the country’s petroleum industry including the actual amount of crude oil extracted from the bowels of our earth and sold as exports by the oil multinationals has persisted for the most part of our post-independence history. In his submission over five decades ago, Bala Usman had pointed out not only the impunity of the international oil companies in their mode of operation in the country but even the reckless flaring of gas which he had identified as a major problem even then. In his words, “Put against the great potentialities of the oil industry as a generator of both industrial and agricultural growth in the whole of our country, what we have gained so far from the industry is paltry. The government in the seven years 1958 to 1966 received a sum of £68.7 million, cash, since that time this sum might now total up £150 million. A few Nigerians (actually about 5,000) have got jobs, mostly semi-skilled and unskilled. A few contractors have made a fortune. But the price of petroleum products from petrol and kerosene to fertilizer, drugs and nylon have gone up. The crude oil is sucked out of our sub-soil, piped straight to the tankers and taken straight to Britain and Western Europe to feed their expanding refineries and petrochemical works and fuel their industries”.

Of course, there is a lot that has changed in the petroleum industry terrain since Bala Usman penned those words. It has generated much higher revenues for the economy over the years but the developmental impact of this has been mitigated by astronomical corruption. The Nigerian Liquified Natural Gas Company (NLNG) has emerged as a viable, profitably and relatively efficiently run company indicating better utilization of the country’s gas resources and with many suggesting this as a model for the NNPCL to follow. To some extent, the current travails of the petroleum industry are also partly a function of the perhaps inevitable politicization of what ought to be essentially purely technical economic public policy issues. On the decision to construct the Kaduna refinery, for instance, Cliff Edogun, in his study, ‘The structure of state capitalism in the Nigerian petroleum industry’, noted that “The issue was whether another expensive refinery situated hundreds of kilometers from crude source was necessary, especially when the mode of withdrawal was to depend on pipelines that are vulnerable and subject to sabotage. The technocrats were arguing for cost-saving but the bureaucrats concluded that it would be politically expedient to site a refinery in Kaduna to justify federal character”.

The roll out of locally refined petrol this week by Dangote Industries Limited is good news from an embattled sector but the much sought-after relief that this is expected to provide consumers may not be immediately forthcoming due to continued inefficiencies and opacity in the industry as well as complications associated with the interplay of market forces. Beyond this, how much of the monumental Dangote Refinery is reflective of local knowledge and domestic mastery of the industry’s technology thus stimulating confidence in Nigeria’s enhanced capacity to autonomously optimize its potentials for the country’s future transformation?

Even as we daily suffer from our incapacity to refine crude oil locally, we read and see daily in the media how security agencies ceaselessly destroy hundreds of illegal refineries operated by enterprising locals to refine the commodity admittedly in a rudimentary and crude manner. But can’t they be empowered with the requisite skills to refine the crude more professionally and thus add their output to our legal stock of local capacity? I recall once again the words of the late Professor Pius Okigbo at the First Obafemi Awolowo Foundation Dialogue in 1993 that during the civil war, the Biafran scientific community, among other feats, “succeeded in building out of entirely locally fabricated materials a giant petroleum refining facility and thereby made the technology so diffuse and more universally understood and applied than anywhere else in the world”. Surely this should not be unattainable rocket science to us in today’s Nigeria.