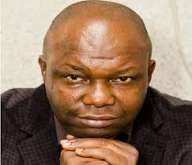

Obasanjo craves honour and respect but routinely scorns others. His Iseyin affront climaxed life-long lack of grace.

In his book, Not My Will, written as former Head of State and retired army General, Olusegun Obasanjo mocked revered sage, the late Chief Obafemi Awolowo. He said the federal power Awo craved all his rich, long life, he — Obasanjo — got effortlessly gifted! He just got off at the time on the high as the first Nigerian soldier to hand over power to civil order in 1979. He crowed, derring-do, with the bluff and bluster of a callow youth dazed by his own rather self-surprising feats.

In 2023 (September 5, to be precise) at his “departure lounge” — to use Obasanjo’s own favourite quip for deep old age — the former two-term elected president, at Iseyin, Oyo State, spewed bristling sacrilege. He ordered traditional rulers, fully robed in their royal attires, to “stand up!” and “sit down!” with military brusqueness and rudeness. It was the worst abomination a Yoruba-born could ever commit!

Did he still speak with the frothy folly of extended youth? Or with mental dissonance: that creeping debility that comes with old age?

With such shocking, reckless life-long conduct, Obasanjo risks a dire epigram on his tombstone: ‘Here lies the man who craved respect and honour, yet traduced everyone in his path, and thereby hugged utter disgrace at the end.’ That would be a dire after-life testimony. Yet, hardly unfair — except, of course, he eats crow in public, in the same full glare he disgraced the royal fathers — by showing remorse via a public apology. But will he? The odds are high!

The odds are high because Obasanjo, perhaps pleading his rough and gruff military temper, has all his life been impunity personified — and unrepentantly so. Indeed, that penchant to stand on his dignity, that self-gifted democratic licence to insult others and crow its finest of regnant conducts, is the most recurring behavioral toxin in Obasanjo’s public life. Perhaps his private life is different?

Take all his autobiographies, fired by thumping narcissism and preening megalomania: My Command, Not My Will, My Watch. In all, Obasanjo projects himself as the superhero before whom everyone must bow and tremble, or otherwise get savagely bruised by the author’s tumbling and scathing adjectives.

In My Command, he ridiculed the late Brigadier Benjamin Adekunle as a near-incompetent war commander. Yet, everyone knew that Adekunle, with his 3rd Marine Commando division, did most of the gruelling war tasks before Gen. Yakubu Gowon, as commander-in-chief, decided to hand Obasanjo that command, at the tail end, when the Civil War (1967-1970) was nearly won and lost.

In Not My Will, aside from ridiculing Awolowo – Awo who in death is more revered than living Obasanjo would ever be — the Balogun of Owu dragged Gowon, his old commander-in-chief, in scurrilous mud. For unproven allegations that Gowon was involved in the coup attempt that killed Gen. Murtala Muhammed on 13 February 1976, Obasanjo claimed he had stripped Gen. Gowon of his military title, dismissed him with “ignominy” and sentenced “Mr. Gowon” to trial (read the hangman) any time he set foot in Nigeria!

But piquant irony: the one that stripped Gowon of his military title in 1976 is being entirely stripped of his entire Yoruba chieftaincy titles for glaring disrespect to Yoruba culture and the traditional institution that conferred on him such honours. The Igbimo Apapo Yoruba Agbaye (Yoruba Council Worldwide) just made that proclamation. Another irony: similar phantom allegations would later rope Obasanjo and his former No. 2, Major-Gen. Shehu Musa Yar’Adua, into an alleged coup attempt under Gen. Sani Abacha in 1995. Obasanjo was lucky to escape with his life. Yar’Adua, not so. He died in that gulag. Sad comeuppance — from implacable karma — for the Gowon slight?

Indeed, had the British government yielded to the Obasanjo junta’s hysteria for Gowon’s deportation, he probably would have been railroaded onto the executioner’s stake. Yet, Gen. Gowon today lives in quiet dignity befitting of a quintessential officer and gentleman, as distinct from the rude species that Obasanjo often projects.

In My Watch, Obasanjo characteristically descended on others, except his few poodles, painting Vice-President Atiku Abubakar with the tar Obasanjo could himself be fairly and legitimately painted with. Both went for personal glory while the country in their care decayed.

But away from peer gracelessness, Obasanjo’s Iseyin outrage — a cultural heresy driven by blind impunity — wasn’t his first fragrant slap, smack in the face of Yoruba traditional institutions. His rotten charity had indeed began at home! In 2004, as Nigeria’s sitting President but Balogun of Owu and co-kingmaker with five others, Obasanjo not only shredded the majority choice among the kingmakers, he set security agents after three of them, just to impose his will, no matter how skewed or crude. That created quite a stir but Obasanjo in the end had his way.

Ironically though, the point Obasanjo made in Iseyin was spot on: in temporal matters, the President or Governor or even the local government chairman holds authority over traditional rulers in their domain. That is correct but trite — hardly deserving of any rude lecture.

However, in the cultural milieu, that all-powerful temporal boss is happy and eager subject of his local royal father. That is why Obasanjo, and the so-called modern elite, would cheerfully bow before traditional rulers for local chieftaincies.

His personal tragedy, by that Iseyin abomination, is being insensitive to that delicate cohabitation between temporal and spiritual powers in Nigeria’s public space. It’s the first lesson any public official learns, particularly in Yorubaland where the kings are rated only next to the gods in spirituality, under the supreme guidance of Olodumare.

It’s not as if the Balogun of Owu, himself a courtier in that proud tradition, is ignorant of that practice. It is more likely his inherent rascality bobbed up at the wrong time! It was a joke taken too far, which ramifications he cannot even start to decipher. The same Obasanjo that ridiculed the bevy of royals at Iseyin had publicly prostrated before his own Olowu of Owu-Egba. He did so too before Oba Enitan Ogunwusi, the reigning Ooni of Ife, the Yoruba spiritual fount. Why? He even knelt — publicly — before the young Ogiame Tsola Emiko, Ogiame Atuwatse III, the reigning Olu of Warri.

Don’t be deceived though: these ringing contrasts, swinging from utter rudeness to exaggerated politeness, nestle side-by-side in Obasanjo’s queer world of showy hypocrisy. It’s the dissonant psychology of a one-sided mind that craves reverence, is incapable of according others basic of respect, yet is surprised that what he reaps is near-eternal scorn.

Let Obasanjo beg for pardon over his public folly at Iseyin. Otherwise, let him ready himself for whatever sanctions to follow — the making of the Yoruba pariah scorned by all.

Only the tragically deluded declares himself lord and master over his culture — and essence. That is hubris that only comes before the big crash.

“Let Obasanjo beg for his public folly at Iseyin. Otherwise, let him ready himself for whatever sanctions to follow — the making of the Yoruba pariah scorned by all.”

Credit: The Nation Newspaper