By Simon Kolawole

On December 31, 1983, I was but a tiny secondary school kid when Brig Sani Abacha announced the overthrow of President Shehu Shagari. The economy was in a complete mess, measured by the skyrocketing cost of living. Oil prices had dropped below $10 per barrel and foreign reserves had fallen to $1 billion — compared to a fairly healthy $10 billion in 1980. Prices of basic commodities doubled in a short while and factories started closing down as forex scarcity bit hard. Everything was going haywire. Abacha’s voice that early Saturday morning brought relief to millions of Nigerians who expected the new military government to tackle the inflation and restore sanity to the economy.

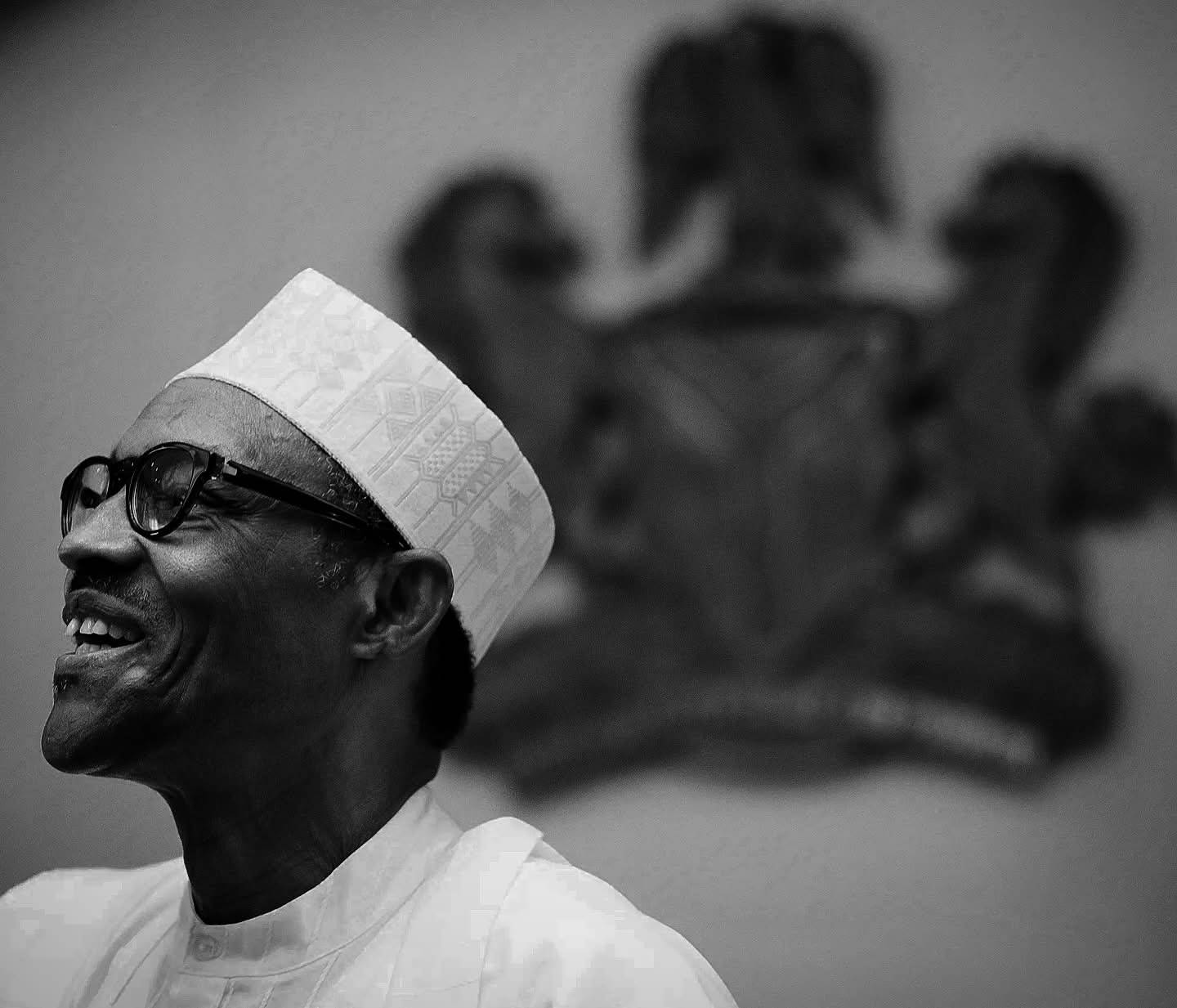

Much later in the day, Major Gen Muhammadu Buhari was unveiled as the new head of state and Brig Tunde Idiagbon as the chief of staff, supreme headquarters — or No 2. Buhari instantly set out to work, preaching the virtues of patriotism and orderliness, launching the War Against Indiscipline (WAI), and jailing corrupt politicians, some for 500 years. But the economy remained in a bad state. At the time, I knew nothing about how the economy works and thought Nigerians were suffering because their leaders were wicked. I was too young to understand the links between production, consumption, exports, imports, the value of the naira and the overall health of the economy.

Worse still, I thought the economy was something to be fixed with military orders, price controls and popular opinion. With Nigerians still in the grip of untold economic hardship — coupled with the military highhandedness that saw journalists, critics and activists being arrested and detained without trial — there was another huge sigh of relief on August 27, 1985 when Brig Joshua Nimyel Dogonyaro announced the overthrow of Buhari. I celebrated, more so as the new head of state, Maj Gen Ibrahim Babangida, started to paint the picture that he was going to be a different, liberal kind of leader. He called himself “president”. He subjected economic reform decisions to public debate.

Babangida’s reforms under the structural adjustment programme (SAP) led to the liberalisation of the forex market, removal of subsidies and more pains. Nigerians began to regret Buhari’s exit. The refrain became: “Buhari’s government was not this bad.” I only started having a soft spot for Buhari in the mid-1990s when he admitted to TheNews magazine that his government made many mistakes but said they were “honest mistakes” because “we were in a hurry to change things”. Those words touched me. He came across as someone with a genuine desire to change Nigeria. I began to see him in a new light and I believed he did well as chairman of the Petroleum (Special) Trust Fund (PTF).

After admiring him from a distance for years, I finally met him in March 2001. I had just been appointed editor of the about-to-be-revamped TheWeek, a weekly news magazine founded by Alhaji Atiku Abubakar. Buhari graciously agreed to speak with me. I travelled to Kaduna to meet him and he gave me a very good interview with which we relaunched the magazine. He was very critical of the Obasanjo administration on leadership, security, corruption and the economy. That edition sold out. We kept in touch. I believed the media had been unfair to him and I took it upon myself to make his voice heard, all the more after I moved on to THISDAY in 2002 and became the Saturday editor.

When Buhari lost the 2003 presidential election, I stood in his corner. It was a badly conducted election, one of the most rigged in our history as at then. Even the Supreme Court admitted it, only saying that there was “substantial compliance” and that if the bloated figures were cancelled, Buhari would still not win. The 2007 election turned out to be worse than 2003 and Buhari headed for the courts again. Because his opponent, Alhaji Umaru Musa Yar’Adua, was also from Katsina state, Buhari was asked to withdraw his petition in the interest of brotherhood. I called to get his reaction and he said bluntly: “I am only thinking about Nigeria, not Katsina state. There is no room for sentiments.”

Buhari was always ready to meet with me to discuss the state of the nation, mostly off the record. However, when I met him in London in May 2009 in company with my friend, Mallam Aminu Hammanyero, I decided to pen the encounter because he said things I did not want to keep to myself. My article was titled ‘Leadership without Conscience’ (THISDAY, May 24, 2009). He was critical of the Yar’Adua administration for reversing Obasanjo’s policies, saying: “When I became head of state in 1983, I announced that we would honour every international obligation, even though some were entered into wrongfully by the previous government. But an agreement is an agreement.”

He said after taking a look at the country for decades, “I came to the conclusion that our leaders do not have conscience.” As evidence, he said: “I was in Calcutta (now spelt as Kolkata), India, in 1972 for my staff training. I remember that the same way refuse collectors come around in the morning was the way undertakers were going round every morning collecting dead bodies for burial. India was facing harsh economic and food crises then. Yet, with purposeful leadership, India had become a different country in a matter of 10 years. When I became head of state in 1983, I was amazed to discover that Nigeria was importing rice from India. That is what purposeful leadership can do.”

I wrote on my encounter with him and he was surprised at how well I captured his thoughts. “Simon, I did not see you with a tape recorder,” he joked. I didn’t capture everything, though. For instance, I recall asking him if it was true Idiagbon was the one running the show when he was head of state. He denied it. “Tunde’s role was to announce the decisions of the Supreme Military Council and interface with Nigerians. There was nothing he announced that was not discussed and agreed upon in council. He did not take any decision by himself.” This was unknown to most Nigerians and that must have fuelled the assumption that whoever ended up as his vice-president would be the one in charge.

When he threw his hat into the presidential ring again in 2011, he asked the late Mallam Abba Kyari to offer me the position of campaign spokesman but — to his disappointment — I said I was not interested in politics. Ironically, it was the same election that dampened my affection for Buhari. I had expected him to come out forcefully to condemn the post-election violence, but his response deeply disheartened me. I then wrote a critical article on politicians and violence, asking: must you serve the people by force? Buhari believed it was aimed at him. He gave me a call. “Simon, thank you for abusing me today,” he said and laughed, but insisted his supporters suffered attacks as well.

With the formation of the All Progressives Congress (APC), it appeared the stars were finally aligning in his favour. He sent a hearty congratulatory letter to me after the launch of TheCable in April 2014 and granted us an interview later in the year. I did the interview along with my colleague, Frederick Nwabufo, and I recall eating a dinner of jollof rice with fried chicken. Mallam Ya’u Darazo, Buhari’s long-term ally, helped to facilitate the interview. By then, I had become a curable optimist. I no longer thought one man could save Nigeria. Agreed, leadership at the very top is important, but in a democratic federation of 36 states, it will take more than one man to tackle underdevelopment.

After he won the 2015 election, I called to congratulate him. The phone was often with his aide, Mallam Sarki Abba, and I assumed it was Abba’s. It rang out. A day later, I got a call from the number. “Mallam, I tried to reach you yesterday,” I said, thinking it was Abba. The voice said: “How are you, Simon? This is General Buhari.” I froze in disbelief. He went on: “I had several missed calls. Sorry, I’m just returning yours.” I congratulated him. But in my mind, I did not expect miracles. Boko Haram would not vanish overnight. The economy would not recover magically. Despite the sweet campaign promises, I knew there was no easy way out. Pains awaited us no matter the choices he made.

My final one-on-one with Buhari was in October 2018, this time in Aso Rock. I offered a frank assessment of his administration, specifically the security situation and the in-fighting in his government. I said to him: “People are asking, where is the Buhari of 1984?” On the menace of the herdsmen, he asked me: “Do you honestly believe I asked herdsmen to be killing people?” I could feel his pain at this point. “No, Your Excellency,” I replied, “but people are talking about your body language. When OPC was attacking northerners in 1999, Obasanjo ordered the security agencies to shoot on sight. I don’t know if he meant it, but the OPC boys got the message and mellowed down.”

Buhari spoke like a man betrayed by those he trusted, most of whom only looked after themselves. He complained about an appointee who disobeyed his directive and I asked: “Why didn’t you fire him? People say you are the best employer of labour in town, that you never sack anybody.” I’m not too sure he was comfortable with my critical comments. I left the meeting that evening asking myself: “Hope I have not just disrespected the president of the Federal Republic of Nigeria…” I last saw him in flesh at his 80th birthday dinner in December 2022. Last month, I heard he was in a UK hospital. I thought it was a routine check-up. I was also in the UK but chose not to disturb his peace.

You can imagine my shock at the news of his death last Sunday. He had looked quite healthy after his near-death experience of 2017. At 82, he definitely did not die young. Nevertheless, I could not hold back the tears. Opinion will forever be divided on his tenure. Some mourned and said he was the best. Others mocked and said he was the worst. The truth, as with many things in life, is always somewhere in-between those extremes. Regardless, Buhari sincerely believed he could lead Nigeria to the Promised Land. He later realised that there is a big difference between theory and practice. It takes more than one person’s integrity and modesty to overcome inflation, insecurity and poverty.

AND FOUR OTHER THINGS…

ON THE MARCH AGAIN

Alhaji Atiku Abubakar has officially resigned from the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP) to join the African Democratic Congress (ADC). This is the third time the former vice-president would resign from the PDP to pursue his presidential ambition elsewhere. He will be 79 during the 2027 elections and this must be considered his final realistic chance of being elected president, but you never know. By leaving the PDP, Atiku has somehow outwitted Chief Nyesom Wike who might have thought his stranglehold on the once-great party would stifle the plans of his rivals. I think the ADC option is a smart, strategic choice by the opposition. It is now up to them to make the best of it. Fascinating.

UNREFINED MINDSET

Here we go again. When President Obasanjo sold two refineries in 2007, we screamed “cronyism”. The reversal of the sale by President Yar’Adua not only perpetuated the rehabilitation fraud but we also ended up 100 percent dependent on imported petrol, burning precious forex. At a time, we were spending almost all our forex earnings on fuel imports. We were even mortgaging future crude output just to import petrol. Well, after a reported $18 billion wasted on “rehabilitation” in 18 years, we are yet to get an apology from the do-gooders, who have again started opposing selling the refineries. A sensible thing would be to insist on due process in line with the PIA 2021. Regressive.

BASHING BOSS

Last week, I went hard on Mr Boss Mustapha, the former SGF, for appearing to downplay the role of the other parties in the merger that brought President Buhari to power in 2015. After seeing the video, I realised I misunderstood his analysis that the other parties (including the ACN, of which he was deputy national chairman) brought only “three million votes” to the merger, with Buhari providing his regular 12 million. Apparently, he meant they took a strategic decision to merge with Buhari’s CPC because of his vote bank. He was not downplaying the “three million”. Ironically, his attempt to hedge with “this may sound controversial” only stirred controversy. Self-fulfilling.

NO COMMENT

So far this year, we have lost two very prominent elder statesmen: Chief Ayo Adebanjo and Chief Edwin Clark. They died within days of each other. Oba Owolabi Olakulehin, the Olubadan of Ibadanland, has also died. Oba Sikiru Kayode Adetona, the Awujale of Ijebuland and paramount ruler of the Ijebu people, died same day as President Buhari, who ruled Nigeria both as a military man and as a civilian for nearly 10 years. I have googled doggedly and can’t find any of our famous prophets giving any hint at the possible deaths of these eminent Nigerians — not even the low-hanging fruit of saying that “a former head of state should pray seriously for good health this year.” Hahahaha…