By Segun Ayobolu

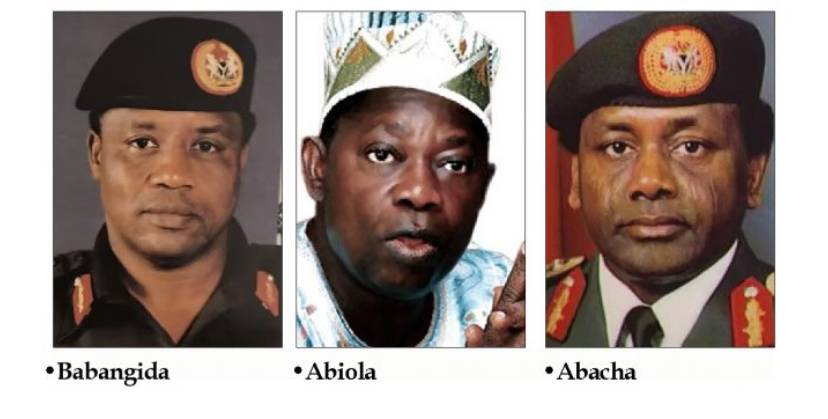

Self-styled former military President, General Ibrahim Babangida’s long-awaited memoir, ‘A Journey in Service’, brings to the forefront an earlier book, published in 2010 titled ‘Diary of a Debacle: Tracking Nigeria’s Failed Democratic Transition (1989-1994), authored by renowned journalism scholar, inimitable satirical columnist and diligent public intellectual, Professor Olatunji Dare. In the light of IBB’s account in his book of the reasons for and the personalities behind the annulment of the June 12, 1993, presidential election, now confirmed to have been won by Chief MKO Abiola, Professor Dare’s ‘Diary of a Debacle’ acquires greater poignancy, saliency, relevance and significance.

For in delectable after delectable column giving a ringside account of events as they unfolded before, during and after the annulment including the pronouncements and actions of the major dramatis personae, Professor Dare proves conclusively that IBB did not have any intention of leaving power and thus made no effort to reign in those of his military colleagues that he belatedly admits in his book, were vehemently opposed to the transition from military dictatorship to a democratically elected government.

Professor Dare’s disdain and dislike for what he perceived as IBB’s duplicity, slipperiness and Machiavellian disposition is unhidden in his chronicles of events surrounding the annulment but he hardly ever succumbed to the passions of raw anger or blind outrage. Yet, Dare had much to be displeased with as regards the IBB dictatorship. His newspaper, The Guardian, was one of the courageous voices shut down for prolonged periods during IBB’s inglorious reign. His pungent and popular columns understandably attracted the close attention of the regime’s security goons.

His refusal to be part of a delegation to apologize to the military to facilitate the reopening of the newspaper rendered him virtually jobless. Yet, his articles were couched with characteristic literary and linguistic flair and the facts were presented with the meticulous diligence and integrity of the professional historian. A resort to anger, vulgar insults and cheap abuse would no doubt have devalued their intellectual worth and diminished their worth as reliable historical documents.

Those responding in fiery anger to IBB’s memoir may have some lessons to learn from Professor Dare’s class and style in the presentation of his material. Can it be that there is absolutely nothing of worth and not a single iota of truth in a memoir of over 400 pages? That would be an intellectually dishonest overgeneralization. For a dictator who ruled the country for eight years, we surely should be interested in a dispassionate analysis to situate his place in Nigeria’s history. Much more important and critical than his regime’s Political Transition Programme that produced the annulled June 12, 1993, presidential election was its Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) which was its flagship economic policy.

There are those who contend that there was no alternative to SAP at the time the Babangida regime came to power in August 1985. The austerity measures and remedial economic policies implemented by the preceding Shehu Shagari civilian administration and the General Muhammadu Buhari military regime were simply not producing the desired effects. Professor Adebayo Olukoshi analyzed some of the Buhari regime’s policies such as devoting over 44% of the country’s total foreign exchange earnings to debt servicing and the policy of counter-trade which involved bartering Nigeria’s crude oil for raw materials, spare parts, machinery and consumer goods from a number of countries.

In his words, “In the face of this, the problems of the Nigerian economy worsened, with inflation still rising further, infrastructural facilities deteriorating, more workers losing their jobs, the payments problem persisting, the industrial sector suffering more setbacks and the agricultural sector stagnating”. All of these increased the intolerance and authoritarianism of the Buhari regime and facilitated the successful Babangida’s palace coup in 1985.

The core of the IBB regime’s SAP was the massive devaluation of the Naira and the country has continued to suffer from its debilitating effects to this day. Commenting on the consequences of the devaluation of the Naira and the introduction of the Second Tier Foreign Exchange Market announced on February 26 September, 1986, the late Pa Alfred Rewane, had written that “As my friends and I discussed the implications of the government’s announcement, I expressed the view that the devaluation of the Naira was a recipe for disaster and that within five years, the Naira would be worth less than 20 per cent of its then existing value, leading to the possible collapse of the Nigerian economy”.

Rewane continued, “I reminded them of a standard economic argument that devaluation of the national currency is best contemplated where the nation’s economy depends largely on the export of manufactured goods for its foreign exchange earnings, and where devaluation is considered appropriate to ensure the competitiveness of its manufacturers. I went on to say that, for a country like Nigeria, which earns the bulk of its foreign exchange from the export of crude oil and a variety of agricultural products, such as cocoa, groundnuts, palm produce, rubber etc, there is no advantage in devaluing its currency”.

Unfortunately, Pa Rewane ‘s prediction has been all too true. The IBB regime’s SAP resulted ultimately in the massive de-industrialization of the economy, phenomenally increased unemployment, the virtual wiping out of the middle class and widespread increase in poverty levels. But as evidenced by the minuscule number of billionaires at his book launch, who raised N17 billion for his presidential library within an hour, his regime also created a new class of super-rich Nigerians whose wealth was predicated more on government patronage than any outstanding ingenuity or extraordinary skill or creativity.

However, the administration’s Political Transition Programme was fashioned to protect and preserve the SAP and make it a permanent policy feature in Nigeria. Thus, while the SAP undertook a far-reaching deregulation of the Nigerian economy, through the privatization and commercialization of state-owned enterprises, considerable whittling down of fuel and other subsidies, deregulation of prices and interest rates, trade liberalization, reduction of public expenditure and removal of administrative controls in foreign exchange transactions among others, the Political Transition Programme was highly regulated and characterized by rigid military regimentation.

That is why any elections conducted under this suffocating military-political environment can be described as the freest and fairest in Nigeria only within necessary contextual limits.

IBB’s Political Transition Programme involved the patently undemocratic banning, unbanning and rebanning of so-called old-breed politicians, the imposition of two government-created parties, the National Republican Convention (NRC) and Social Democratic Party (SDP), the imposition on these two parties of government created manifestos and constitutions positioning the parties a little to the left and a little to the right of a centre determined by the military. But for the banning of the so-called old-breed politicians, it is unlikely that either MKO Abiola or Bashir Tofa would have emerged as presidential candidates of either the NRC or SDP. It is certainly not fortuitous that the two presidential candidates that emerged were close friends of IBB.

Again, in the earlier presidential primaries that were held, General Shehu Musa Yar’Adua had emerged the clear winner in the SDP while Alhaji Adamu Ciroma and Alhaji Umaru Shinkafi were heading for a run-off in the NRC. However, IBB cancelled the primaries in which two northern candidates were emerging alleging monetization of the process and he received widespread approbation in the South for this forerunner to the annulment of the June 12, 1993, presidential election. Indeed, some newspapers in the Southwest wrote front-page editorials commending IBB for the cancellation of the primaries. When his regime eventually annulled the June 12 election so clearly won by Abiola as IBB himself has now admitted, it is understandable that the criminal act received little condemnation outside the Southwest.

IBB and the other pro-annulment forces within his regime had obviously presumed that MKO Abiola could be placated with government patronage or induced like Elesin Oba in Wole Soyinka’s ‘Death and the King’s Horseman’ with the pleasures of the flesh to forgo his mandate. But the billionaire businessman and Egba warrior chief rose to the occasion, stood doggedly by his mandate and lived up to the saying of the Yoruba that a honourable death is far more desirable than a shameful existence.

There are those who condemn IBB as being cowardly for blaming others like Abacha for the annulment although taking responsibility as the one ultimately in charge at the time. They contend that he could easily have retired Abacha and the other officers opposed to the transition programme. But this view underestimates the complexities of politics within a military regime despite the unitary character and rigid hierarchical structure of the military as an institution. From what we know of Abacha, would he just have quit meekly if sacked or would he and his loyalists have fought back ferociously even if it meant bringing down the roof on everybody?

General Yakubu Gowon was alerted about a coup plot against his regime before his trip to Uganda for the meeting of the Organization of African Unity. But there was little he could do but meekly accept his fate with philosophical equanimity. General Obasanjo was military Head of State after the demise of Murtala Mohammed but the powers behind the throne were Generals Yakubu Danjuma and Musa Shehu Yar’Adua. Military politics may be more intriguing and intricate than we think.

What will be the final verdict of history on IBB, MKO, Abacha and other dramatis personae in the confounding conundrum of the June 12 annulment? Was IBB the sole villain with no redeeming feature whatsoever? Was he in the final analysis an embodiment of the weaknesses and limitations of the collective Nigerian society and character, features which he thought he understood and sought to manipulate but which finally undid him? Or is there as the famous Gbolabo Ogunsanwo once famously asked an IBB in us all?