By Sam Omatseye

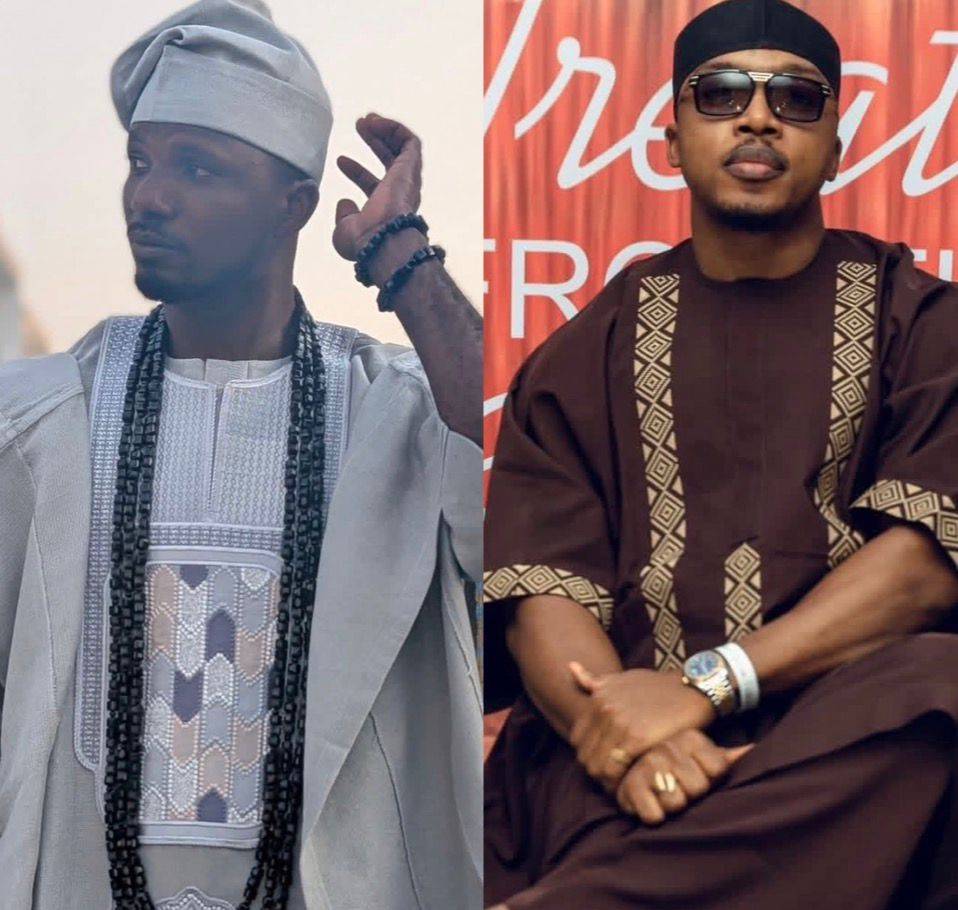

Two episodes last week show how politics in the Southwest sets it apart from other parts of the country. They are the ouster of the Lagos State House of Assembly Speaker, Mudashiru Obasa, and the enthronement of the new Alaafin of Oyo, Oba Abimbola Owoade.

Both incidents happened without incident before they looked like an accident to the losers after they fell flat. Then the defeated with broken jaw and mouth agape wondered at their lack of vigilance, or naivety. They are like the goal keeper who did not see the suave swerves of Haruna Ilerika until he put the ball in Yakubu Mambo’s feet and the ball was behind the net.

In Lagos, Obasa was in the United States but he was beheaded in Nigeria. In Abiola’s favorite proverb, they shaved his head in his absence. He did not know he was bleeding until they told him his head was off. When Romulus Augustulus, Roman Empire’s last king was told that Rome had fallen, he said. “I just fed it a few minutes ago.” He named his peacock Rome and he thought they were referring to the bird, not his fallen state.

In Nigeria, it was Monday. In the US, it was Sunday when Obasa’s calabash broke. He was defeated not only by his fellow lawmakers but also by time. Technically, if he was impeached on Monday, it was Sunday in the US. He was still speaker. That is the illusion of time. Once he stepped across time zone, he had stepped into zero. The reality was that he was speaker no more.

Thirty-two lawmakers had converged on the assembly. No headlines about a plot. No claims or counter-claims about the hubris of the man who kept a governor in the lurch for hours just because he wanted to submit a budget, or a superlative claim about being better than anyone, including his godfather. No newspaper bullies or street protests. No omens. Just an amen at the end. Within five minutes, the men and women came together, wielded the sword and lopped off the man who had been the Capo or, shall we say, capstone of the House. It was the intrigue of silence, or the silence of intrigue, at least something of each. We can call it a ritual of violence minus the blood, or a bloodless coup. The impeachment came on the sly. We can call it a sly slam.

The same applies in the fight for the revered throne of Oyo. Oyo goes way back in that sort of theatre. It invokes some of the 19th century battles on that throne and the ferment of the Yoruba Wars. It had palace intrigues, egoism of a powerful man, the collision of altars between temporal and spiritual forces, as well as the intrusion of the north and its faith. There was the Oyo Mesi, just like the days of Bashorun Gaa, or the 1840 Battle of Oshogbo when the horsepower of an invading army fell to the spies and wiles of a Yoruba resurgence. In today’s case, there were stories of Islamic evangelists on a spree in Oyo. There was the corrupting power of money, or an allegation of it. There was not much money in those days, but the influence was as potent as money. As Oscar Wilde asserted, “all influence is corrupt.”

Of course, Governor Seyi Makinde was at work, under the shadows. The others, including the Oyo Mesi thought they had it wrapped up. Until they were wrapped up. Now, the governor speaks of EFCC. Of course, Prof. Wande Abimbola played the role of the mystic and power. It is moot point whether it is the triumph of the spiritual over temporal, especially since the Bourdillon Constitution and house of chiefs. The traditional authority has been subordinated to the political.

Oba Owoade has mounted the throne, and the others are just waking up to the faecal dust of their humiliation. The Oyo story recalls the opening chapter of Charles Dickens’ A tale of Two Cities set in the turmoil of the French Revolution. “There was a king with a large jaw and a queen with a plain face, on the throne of England; there was a king with a large jaw and a queen with a fair face on the throne of France…Spiritual revelations were conceded to England at that favoured period…”

In this case, spiritual revelations favoured Owoade through the ifa to the Governor. Prof. Abimbola said the Oyo Mesi has affirmed the inviolable verdict of the gods. Go figure.

That is a picture of Southwest politics. In Lagos and Oyo, it was politics as clinical acts. The victims had fallen flat before realizing they were no longer on their feet. The acts were fait accompli before the opponents knew their fates. It was politics without noise, or politics to defer the noise. It has voice but articulated in whispers. The winner claims the crown before acclamation. It is a politics without boast but it is a defeat of bluster.

This is a contrast to what we see in other parts. For instance, the battle between Sim Fubara and Nyesom Wike takes place on the rooftop. Everyone has a ringside seat, popcorn and drinks in generous supply. Each side knows the other side’s strategy. It’s a battle of press releases, of interviews, of jaw-jaws and war-war, and claims and blusters. The dirty linen is so dirty, everyone ogles the pig fight. There is no courtesy, no party, no hugs, no drinks or cheers, no public laughter together. It is what the Yoruba call Ija igboro. Someone calls it mutually assured destruction.

We are seeing it in the north as well, like the agonized outcry of Emir Sanusi, who said “I don’t want to help this government.” He gloated that he would watch the movie as the government “stews.” The only conciliating thing he said was that the government measures were “a necessary consequence of decades of irresponsible economic management.” But it was by no means said in a tone of praise. He was trying to echo his own support, without saying it, for the collapsing of the foreign exchange regimes and removal of fuel subsidies that he had advocated for about a decade now. He relented later by trying to unsay what everyone heard. He said critics took a paragraph out of context. But all he said is not more than a paragraph. He was apologizing without remorse.

We are also seeing the battle of the throne in Kano, between him and Ado Bayero, and it is no more than an open brawl. It is a battle of a big throne and a small throne, with two big egos with atavistic bloodlust. Unlike the Dickensian tale, they are not in two countries but only in one kingdom: Kano. Someone calls it mutually assured destruction.

It was the same case with some noisemakers about the tax bill, who said they did not read it, and would not read it. Now, they are backtracking. They read the document after speaking, and they realise that communication is better than noisy and extravagant poses.

The Yoruba style comes out of the concept of Omoluabi or what the Greeks call paideia. It enjoins respect for the elderly, restraint of temperament, kindness to strangers and, in a grievance, dialogue first even if you know your case is just. When all fail, look for the target of opportunity. Patience is virtue. Babatunde Raji Fashola (SAN) said, “anger is not a strategy.” Yorubas often shy from foul language or rhetoric of the frustrated. Ambush is better than open fight. The noisy rabble rousers of the tribe are the distractions the real power brokers need to go for the real McCoy.

This is why Yoruba history intrigues. Sometimes they can be misunderstood when they say a thing, and the uninitiated would not understand they are saying something else. When Awolowo asserted during the Nigerian crisis that if the East is allowed to go, the West would as well, Ojukwu and his men did not understand the nuances of the man. How could the West secede when it had no army of its own. The officer corps of the Nigerian Army was dominated by the East, but the men were from the North and Middle Belt. The northern soldiers had occupied Yorubaland. How could Awolowo, in spite of any grievance, urge rebellion?

Hence, he engineered a meeting attended by Samuel Mariere, Ojukwu, Aluko and a few others. He tried to tamp down Ojukwu’s rage. If Awo shared secessionist sentiment, it was a goal without wherewithal. He tried to dissuade Ojukwu from war. In Wole Soyinka’s memoirs, You Must set forth at Dawn, he said after the meeting, Ojukwu met Awo in private and said the East was going to war anyway. Awo thanked him for his honesty, but asked Ojukwu for a favour. He should give him a notice before announcing it. Ojukwu didn’t. After he announced, Awo joined the Gowon government, and the war was essentially won by officers from Yorubaland, especially the third Marine Commando. No one knows why Awo asked Ojukwu for that favour. But it is on record that Awo resented northern soldiers in his homeland and asked Gowon to evacuate them. After some resistance, Gowon obliged.

History will always have its mysteries.

Awo acted the methodical Yoruba, privileging result over fuss. When it comes to such clear-eyed battles, they remind one of the words of the notorious colonel in Garcia Marquez’s immortal novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude: “The best friend a person has is the one who has just died.” It is politics in the clinics of a go getter. That is also the temperament of the world’s great powers of history: The United States and Great Britain. Harry Truman said: “If you want a friend in Washington, buy a dog.” Lord Beaverbrook, Churchill’s friend and associate, once said, “a man with a will to power can’t make friends.”

This is how the Southwest is when it is provoked. But when you play friends, they are friends. It is like Shakespeare’s assertion that “Beware of entrance to a quarrel, but being in, bear it that the opposed may beware of thee.” The Yoruba saying encapsulates it this way: “Iku n’de Dede, Dede n’deku.” Dede is a man. Translation: Dede baits death and death baits him.

Awo learned it and played it until he himself lost that cunning as he grew old, so his politics did not give him the meaty prize of his ambition. It was not the Awo who won the war, or who spearheaded the cross-carpeting of the First Republic that cost Zik the premier in the Western Region. Awo has passed on the baton.

Culled from The Nation