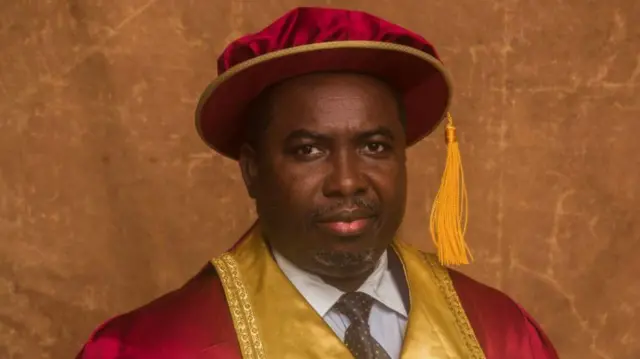

By Arakunrin ‘Rotimi Akeredolu, SAN

I must hasten to thank, profusely, the organisers of this annual event for the invitation to speak at a gathering, such as this one, which comprises eminent citizens and an array of the best for which our profession is always proud. I congratulate the NBA, Ikeja Branch, for the consistent interventions in national politics and social issues. The fitting sobriquet, “The Tiger Branch”, is not misplaced.

I thank you for keeping faith with a very important aspect of the creed of the legal profession. It is expected of us to show the way whenever there appears to be confusion in the country or at any level of engagement. We are called learned, not because other professionals are not useful in their respective rights. Since the foundation of a modern society is predicated on the principles of law, it becomes incumbent on lawyers to guide in the interpretation of terms, akin to taxonomic constructs, for better understanding.

Above all, our insistence on the application of these cherished and tested principles, in the best manner possible, should be an abiding preoccupation. We must engage, continually, all the institutions of governance in the polity until the desirable becomes achievable. We must continue with relentless inquisition of aberrant phenomena. Disquisition must be ceaseless in our quest for proper understanding of precepts.

Borrowing practices from civilized climes to suit socio-political expediency, without being properly grounded in the nuances of the received precepts, will, inexorably, lead to confusion and, ultimately, anarchy. If development is a process and not an event, the path leading to advancement must be trodden with a great measure of cognition with regard to the established routes. A country should possess a distinct socio-cultural identity which must, necessarily propel her in the itinerary towards development.

No civilization, both ancient and modern, ensued without a strict adherence to principles which assisted in the achievement of set goals. From Mesopotamia to ancient Egypt, through the Chinese, Greeks and Romans, chosen patterns of existence and vision for the attainment of greatness dictated the pace of progress. Contacts through trades, wars, migrations and, lately, colonization, brought peoples of different backgrounds together. The commonalty of aspirations to survive in a new milieu, under a new political arrangement, often created harmony and accelerated the pace of development.

The circumstances under which some societies existed as either vassals, dependencies to dominant communities, or an amalgam of settlements brought together by exigencies, left no other options than assimilation, achieved, in many instances, after gruesome pacification. The received practices were, most times, imposed and the attendant consequence is hybridization. Once the local elites struggled to be accepted by the leadership of the ruling class. It would reject all practices associated with the indigenous populace or, at best, embrace the old system with condescension and a display utmost contempt to depict rejection of the traditional value system.

A wholesale acceptance of the foreign socio-legal cum political system is the result. There can be no development under such circumstances. The original intention of the overlords had never been to create geo-political spaces of independent and resourceful subjects. The economic structures erected was to ensure maximum expropriation of local resources for the benefit of the home country. The political system made this possible. Therefore, any expectation of real growth and development under such an arrangement becomes illusory.

It is delusional for any society to aspire to greatness while depending on a system which alienates the mass of the people from the processes of producing goods and services for their own good. There can be no good governance from a political order whose overriding interest is exploitation. The determinants of growth for ultimate development are easily discernible. Socio-economic infrastructure, such as the massive construction of public buildings, hospitals, roads, rail lines and bridges, are usually considered as signposts of development. A critical examination of the importance of these facilities to economic growth and the benefits derivable by the people reveals an impersonal and effective arrangement to dispossess and appropriate. Any political system operated in such a place, however so called, cannot represent the yearnings and aspirations of the people without proper adaption to local realities.

DEMOCRACY AND ITS MALCONTENTS

The widely acclaimed and practised political system in the world today is the one associated with liberal democracy. This is so for the promise of the right to participate in decision-making which it presents. A modern government is assessed on the extent to which the principles guiding democratic practice are espoused. Periodic elections held to effect change in leadership is an important feature. The semblance of freedom to choose representatives has been the sustaining element of this political system. It is becoming increasingly difficult to see the nexus between democratic practice and development, which must, necessarily, be about the people and the system assists in confronting the challenges faced by them.

Democracy is commonly defined as the “government of the people, by the people and for the people”. Franchise and popular participation are often mistaken as the right of the generality of the people to participate in the decision-making culminating in policy formulation and implementation. Nothing can be further from the truth than this misconception. The participation of the people is limited to the allowance given to choose representatives who are expected to bring to fruition their aspirations for better living conditions. The reality most times leads to disillusion as there is the perennial feeling of disconnect between the people and their representatives.

Democracy evolved as a political concept from the Greeks. The Athenians who embraced the philosophy of popular participation, in the 5th century BC, accepted the severe limitations imposed on their right to be involved in the decision-making process, especially when their economic circumstances excluded them effectively. Women, slaves and foreigners were excluded from the democratic process. Only the adult males who could make it to the market place called “agora” participated.

Their ability to participate was also defined by the preferences of their patrons because of the entrenched patronage-clientele system. The debt nexus ensured that the poor people could not vote against their patrons in a process that was conducted by open acclamation of choices. The agenda were set by the leadership and the people, who were largely illiterates, were merely called upon to put a stamp of popular approbation. The proponents of this concept set out to give the people a false hope. They made them feel important at the period when important decisions were to be taken. It all ended there.

Socrates and many of his disciples, among whom was Plato, believed that it was wrong to put technical issues before the rabble to decide upon. The entire concept of democracy was faulted as misconceived and deceitful. The conclusion was that the people would be shortchanged in the end. And indeed, the people were worse off under a government which was meant to be by them and for their interests. He refused to follow the popular opinion. He was executed for his belief.

The concept, democracy, derives from two Greek nouns. “Demos” means “people” while “kratos” approximates the English “power”, “authority” or “strength”, depending on the context. “Demokratia” in essence refers to the “power” or “authority” of “the people” as defined by the Greek society where popular participation was restricted to only adult males. Every society must, therefore, pronounce on those who constitute “the people” in their democracy.

Competitions, strives, struggle for ascendancy among the elite group in a society will, invariably, lead to an adjustment in the status quo. Some who consider themselves as the best in the society, not in terms of superior intellect, but wealth and family links, will seek to exclude the majority who are regarded as “the people”. Democracy will slide into an aristocracy, the rule of those who arrogate to themselves the right to always be in power. Others are not considered relevant. The Greeks had a singular luck that their society was homogenous. Therefore, the discrimination was mainly in terms of economic status.

Aristocracy soon dissolved into an oligarchy which translates to a government run by a few powerful people in a given society. “oligos” is a Greek word for “few”. “arkein” means “to rule”. Oligarchy in essence is the government of the few for themselves and by either proxies or themselves. The internal contradictions inherent in the establishment of an order which seeks to exclude the majority from decision-making, continually, will make the transition from oligarchy to another phase inevitable.

If aristocracy is the government of those who regard themselves as the best in the society, and oligarchy insists on the logic of exclusion to assuage greed and overweening pride, a new order will be the direct consequence of unending struggles for power. Kakistocracy, the government of the worst persons, the most unscrupulous, felons, unrepentant social deviants, will supplant oligarchy. The society will slip into the Hobbesian state of anarchy and deprivation. Life then becomes “nasty, brutish and short”. “kakos” means “bad” in Greek. “kakistos” refers to the “worst” in terms of character and intellect.

Many scholars and commentators regard the political system adopted by the Athenians as the ideal for the development of a society. The reverence given to anything Greek in terms innovations often ignores the issue of severe limitations imposed on the mass of the people by the very system designed for inclusiveness. Democracy engendered mass poverty among the poor people. Prominent families still held sway in all public matters. It was, therefore delusional for anyone to associate democratic governance with economic prosperity. The model did not actually work for all the Greek city-states. It represented the dictatorship of the minority over the majority.

THE NIGERIAN SITUATION

I share in the anxieties of the moment, not only because I am an active player in the national political arena. My profession, Law, as well as the experiences garnered over time, compels participation and impels an undying thirst for optimal performance, which gives provenance to peace and progress in any political ambience. The choice of this topic is apt; current happenings around the country should excite interrogatories on the utilitarian value of a political system which has yielded pervasive discontent in the land.

It is not uncommon to read commentaries on the perception of progressive degeneration in our affairs, especially since independence. It has also become a pastime to romanticize the glorious past of the pre-independence era and immediately afterwards. The current experiences compel us to inquire into the causes of retrogression. It has become very clear that this experiment at present needs some urgent attention. Applying cosmetic solutions to fundamental problems will serve no useful purpose.

The bringing together of erstwhile autonomous communities under a uniform administrative entity in 1897 was considered expedient for the colonial administration. The British proceeded to merge all towns and villages in both the Northern and Southern parts of the country into Protectorates in 1900. These new political rVealities were glued together through force. Their erstwhile independent means of economic survival had been truncated. All of them were made to join a new production line whose main objective was to serve the Colonial Administration in whatever way was considered beneficial to them. The rural-urban drift was massive as the peasants had lost their peasantry. Unemployment and the attendant poverty became a reality in an emerging political entity.

Nigeria, as a socio-legal fact, started her political journey after the amalgamation of 1914 by Lord Fredrick Lugard. The new colonial dependencies had peoples of disparate and heterogenous backgrounds who were coming in contact for the very first time. They were corralled into a new administration, alien and alienating in all circumstances. Communities, which had hitherto been independent politically and economically, had to learn to adjust to the new situation. This state of affairs led to the agitation for inclusion by some of the colonial subjects who had returned after been educated in England and America. They were joined by the returning natives who had settled in Sierra Leone after emancipation by the British forces.

They wanted to be included in the new administration as local elites. The agitation was more pronounced in the former Southern Protectorate. The indirect rule style of administration introduced in the North kept the local authorities almost intact as they existed before the advent of the colonialists. The 1922 Clifford Constitution, which was not of general application in the new country, was the answer to the politics of inclusion. The British Government nominated Nigerians into the Legislative Council. The new members were largely illiterates. This action was taken to checkmate the growing the influence of the local elites, especially in the Southern part of the country.

The agitation for inclusion did not take into account the disruption in the economic activities of the people which had been disrupted. The major determinant of social mobility and political relevance was the ability to think and act British. The local elites felt very comfortable with the politics of alienation for as long as they were accommodated in the new exploitative arrangement. Poverty deepened among the people who struggled with loss of identity and economic means. The local elites were relentless in their agitation for inclusion which became strident after the return of the war veterans who fought on the side of the British in the Second World War.

The 1946 Richard’s Constitution introduced regionalism which gave the people a semblance of local autonomy. The 1951 Macpherson’s Constitution sought to address the complaints of the political elites for greater inclusion of Nigerians in the administration. The new Regions were given some measure of freedom to determine how best to organize their economic activities while not disrupting the colonial arrangement for maximum expropriation of the natives. The 1954 Lyttleton’s Constitution improved on it and the agitation remained linear. Local elites wanted greater participation in the affairs of the country.

The grant of self-rule for the regions and introduction of universal adult suffrage presented an opportunity for the local elites to mobilise the local populace for real production of goods and services to create wealth. This period witnessed the possibilities of achieving greatness exploiting local potentials. Agriculture was the mainstay of the economy in the three regions. The colonial administration exploited the populace maximally. The new local political leadership exhibited some flashes of inspiration in the mobilization and organization of the local populace for productive activities to create wealth. Such was the confidence in their ability to steer the affairs of their respective regions that they demanded, jointly for independence from British rule.

The 1957 and 1958 Conferences were held in London to discuss the possibility of granting independence to the country in 1960. These deliberations culminated in the 1960 independence Constitution. The expectations of Nigerians were high on the likelihood of the new dispensation ushering in a period of progress and prosperity. These yearnings were not misplaced as these political entities had assumed their distinct identities prior to independence. The South west had offered great promises on how best to administer a people. the competition among the three regions was such that encouraged growth and development.

Real wealth was created for the benefit of the people, even with the severe limitations bordering on moral deficits. The elites in these regions struggled for supremacy among themselves. The rhetoric changed from foreign domination to ethnic battle for dominance. Loss of focus ensued and the nascent country headed towards the precipice for an assured fall and disintegration. The philosophy undergirding civil administration shifted, largely, from the aspiration towards self-sufficiency to ethnic domination. The prominent politicians began a political scuffle which eventually led to the demise of the First Republic.

The Republican Constitution of 1963 is still adjudged the best for the simple reason that the people themselves enacted the law, not minding the circumstances under which it came into existence. The Queen was still the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces as well as the head of the judiciary by virtue of her position as the Head of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council till the enactment of the Republican Constitution which replaced her with an indigenous Chief Justice for the whole Federation.

The evolution was beginning to take shape in terms of the building of abiding structures which would have supported rapid, independent and simultaneous growth of the three regions and the newly created one, the Mid Western Region, carved out of the West. The truncation of the political course of evolution by the military in 1966 serves as the precursor for the myriad of crises which the country has been witnessing ever since. The incursion of the military into the political arena aborted the dream of achieving the lofty ideals which each of these regions had set as a programme of socio-economic liberation of their people, even if executed half-heartedly.

The system would have taken care of the excesses of politicians with the passage of time. The economic growth was steady. Real production was taking place in all the regions. The people were getting trained and engaged progressively. The free education of the South Western Government had achieved a phenomenal success. Professionals were returning after their stint abroad to join the civil service. The Western Region civil service ranked among the best in the world in terms of service delivery. Each region developed at its own pace.

Salaries and emoluments of public servants were not fixed by fiat at the centre. The economies of the regions were controlled by the respective governments. The resources of these places were also controlled by them. They paid taxes to the Federal Government. Each region had its own judiciary independent of the Federal Judiciary. There were appellate courts in each region. The Exclusive Legislative List in the Republican Constitution of 1963 had fewer items. The Federal authorities had exclusive control of the Armed Forces but the regions had their police formations. There were even the local police constabulary for the local government administration and Native Authority administration in the Northern part of the country.

The military introduced a unitary system in 1966. The structures erected to safeguard domination and preserve identities were demolished. The Constitution was suspended and all powers were concentrated in the Federal Military Government. This was the genesis of the dysfunction in the polity. The military created provinces in 1966, and, later, states in 1967, after the successful counter coup of that same year. The new states were created for political expediency. The military leadership wanted to whittle down the growing agitation for secession in the defunct South Eastern Region.

The federal structure was dismantled, successfully, after the military consolidated their hold on power. 19 States were created in 1976 and an additional two joined in 1987. Six more States were created in 1991. By the time the military left in 1999, the states of the Federation had become 36 plus the Federal Capital Territory. These states had become artificial entities which are virtually dependent on the Federal Government for basic survival. Almost all, with the exception of Lagos and Rivers States, rely heavily on the Government at the centre to remain afloat. They are too disconnected from the economic realities of their various states to mobilise the people for serious economic activities.

CONSTITUTION AND DEVELOPMENT

The Constitution of a country is the basic law. Its role in the development of that geo-political space cannot be over-emphasised. It regulates the activities of the various organs of government. It defines the powers of the three arms of government. It describes the scope of operation of the institutions of State. It prescribes the powers of the component units and the Federation. It creates offices and donates powers to them.

The Constitution should not, necessarily, contain every aspect of a country’s existence for it to be functional and effective. The rights of citizens must guaranteed. Their duties must be enshrined too. And since it should be a product of consensus towards achieving a purpose, all federating units should be encouraged to assume their distinct identities. There should be provisions supporting voluntariness of action. Any part of the country which is uncomfortable with the arrangement should be able to opt out of the Federation without violence.

A Constitution must not be used as an instrument of suppression of dissent. It should not be a clog in the wheel of progress. It should not stifle growth and discourage ingenuity. The federating units must be allowed to act as component parts and not as junior partners.

POST INDEPENDENCE CONSTITUTION MAKING IN NIGERIA

As has been stated above, the 1963 Constitution was the first document produced by Nigerians for the administration of the country. it remains, arguably, the best constitution till date. The 1979 Constitution was promulgated by the military government in 1979. The unitary system of government was retained while pretending to practice federalism.

There are features of a federal system, without a doubt. There are the states created by military fiat. A bicameral legislature was also introduced as well as the presidential system. Another oddity is the inclusion of all the names of the 774 Local Government Areas created by the military. In a true federation, only the states are the component units. The local government must be with the states. The States of the Federation are treated as mere political outposts. The autonomy enjoyed by the states is nominal under this current arrangement.

All the subsequent attempts at constitution making followed the same pattern. The 1989 Constitution was not operated for a day. The 1995 Constitution was simply dusted by the departing military and rechristened 1999 Constitution. This is the document that has been amended twice since its promulgation to underscore the extent of sloppiness associated with its preparation. It retains the same structure of dependence which has been the burden suffered by the states. It is not a document that can engender progress. It has been a major source of the current challenges faced by the country.

There have been attempts to amend this document to reflect the agitations of the citizens. All of these moves have been, at best, tokenistic. The Federal Government has become too unwieldly. There are 68 items on the Exclusive Legislative List while there are just 12 items in the Concurrent List. There should be more than a police command in a Federation, more especially in a country of over 200 million citizens. Each State should have its own police as well as an independent judiciary. Real autonomy lies in the ability of the component parts of the Federation to control their resources and pay taxes to the Federal Government.

CONCLUSION

There is the tendency to fall into an error of judgement on the factors responsible for the grinding poverty in the land. The pervasive insecurity in the land, despite the seeming ubiquity of security agencies with varied and overlapping functions may force the conclusion that our lives are worse off as citizens of this potentially great country. The feelings of disappointment and deep hurt have become so pronounced that many are tempted to reconsider their status as members of this large family.

The pessimistic attitudes must be understood within the context of the prevailing conditions in the country. Security of lives and property is a major reason for the presence of government. The overall welfare of the people is the primary cause for submitting to any leadership. Any Government which fails to cater for its citizens is an organized banditry.

While we acknowledge the contributions of the present Federal Government in many areas, it is incumbent on us to admonish all and sundry that until and unless the country is restructured to reflect her divergence and heterogeneity, there will be no end to the people’s misery. The fault is not in our stars. It is in us all. We must be willing to cast bitter recriminations and be frank in proffering solutions to our problems.

There will be no fundamental change unless the country is restructured.

I thank you all for your patience.

Arakunrin Oluwarotimi Akeredolu, SAN, Executive Governor of Ondo State delivered this keynote address at the opening session of the Nigerian Bar Association, Ikeja Branch Law Week on June 14,2022.