By Palladium

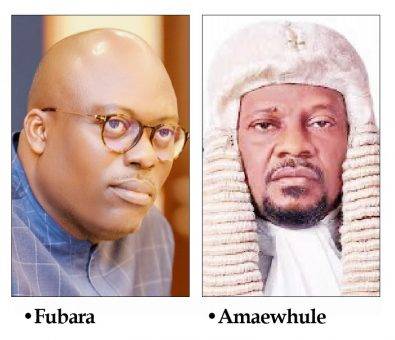

On Tuesday, President Bola Tinubu suspended the main democratic institutions of Rivers State when he proclaimed a state of emergency pursuant to Section 305 of the 1999 Constitution. The House of Assembly, Governor Siminalayi Fubara, and Deputy Governor Ngozi Odu were asked to step aside for six months. A sole administrator, former Naval Chief of Staff Ibok-Ette Ibas, was appointed to run the state for six months in the first instance and restore normality. The National Assembly, in approving the president’s action, anticipated a shorter state of emergency period. In his broadcast, the president predicated his action on the implacability of the warring sides in the Rivers crisis, and the implications for critical national infrastructure, particularly two pipelines vandalised in the Ogoni area of the state on Monday.

The proclamation was almost spontaneous, coming on Tuesday hours after suspected militants blew up sections of the Trans Niger pipeline in Gokana Local Government Area of the state, disrupting electricity supply to parts of Abia State. Given the elaborate preparations necessary to deploy resources and troops to police the emergency, it is unlikely the pipelines vandalisation was anything more than a trigger. The president must have authorised the plan for a state of emergency days ahead of the proclamation. He was more likely to have been influenced by Mr Fubara’s frustrating and deliberate refusal or reluctance to give effect to the Supreme Court judgement of February 28 that compelled him to relate with the legitimate House of Assembly in budget presentation and screening of commissioners.

Regardless of the propaganda the governor deployed, much of it not as clever as he thought, it was clear he had only feigned to implement the judgement.

It is one thing to instigate a welter of court cases, many of them ending in a cul de sac, but it is another thing to deploy propaganda and arm-twisting to undermine the Supreme Court judgement. The governor was clever enough to understand that his tormentor and main antagonist in the Rivers crisis, former governor Nyesom Wike, was not as magnanimous in victory as the situation demanded. Recognising that the former governor’s triumphalism and hysteria had struck a negative impression on the minds of Riverians, Mr Fubara hoped that if he baited Mr Wike long enough, circumstances in the state could tilt the argument against both the House of Assembly and their main backer in Abuja. For the governor, the court defeat was too humiliating, perhaps unfair, and undeserving of implementation. He simply did not see the plausibility of relating with an enemy who had rubbed his nose in the defeat and kicked him in the groin.

The pipeline vandalisation obviously took the crisis a notch further, with Abuja understanding clearly that Mr Fubara had remorselessly turned the ‘guns’ on the nation itself, a heinous crime against national security. But it is even more likely that the state of emergency proclamation was contingent upon factors more insidious. Apart from the governor’s plot to weaken or even invalidate the court’s judgement and render it ultimately nugatory, the presidency also suspected or feared that impeaching the governor could tilt the state into almost irreversible anarchy. Mr Wike had hyperbolically declared that heavens would not fall should the governor be impeached, oblivious to the fear that the state could indeed explode, but the federal government was unprepared to take chances. The presidency would not tie the hands of Mr Wike’s camp to fight back against Mr Fubara, for many reasons including politics, but it knew it had a more salient responsibility to the nation than considering and acknowledging its own political interests. It knew, probably from security reports and even common sense, that Mr Fubara would not go down quietly in the face of impeachment threats, an action that appeared to materialise in the pipeline vandalisation.

Unfortunately for the governor, he had been quoted at a public function as instructing youths of the state not to be ‘perturbed’ about events in the state, but to ‘await instructions’ at the appropriate time. The vandalisation of the pipelines was interpreted as ‘instructions’ given to the youths or militants, while the governor did not condemn the violence or take proactive or reactive steps to ensure peace and order in the state.

Mr Fubara’s serial tragic missteps, more than Mr Wike’s grandstanding and loquacity, contributed enormously to the proclamation of a state of emergency. With one stone, the president defused the violence anticipated over the fear of impeachment and the pipeline vandalisation that could have spiralled out of control damaging the economy and reinforcing other forms of violence if militants and other disaffected Nigerians sensed the weakness or dilatoriness of government. President Tinubu was more than willing to act in ways some legal experts interpret as constitutionally controversial rather than indulge a governor who sadly has a record nearly two years long of defying the law and the constitution.

The proclamation of a state of emergency in Rivers State was unavoidable. The governor, much more than his enemy, Mr Wike, made that outcome inescapable. But there have been a lot of discussions about whether a state of emergency should involve suspending elected officials, in this case, the governor and the legislature. In the first instance, neither the president nor the constitution talked about emergency rule. Section 305 of the 1999 Constitution provides for the proclamation of a state of emergency, and the president in his speech also talked about the same thing. In addition, the constitution does not define the parameters of a state of emergency, how wide or deep. It only defines the conditions precedent to the proclamation. The president, too, perhaps anchoring his wide-ranging action on historical examples, simply left the public to infer the plausibility of how expansively the administration had gone in suspending democratic institutions.

Clearly, after the furore has died down, the National Assembly will take another look at Section 305 of the constitution and attempt to define its parameters, perhaps a little bit more rigidly than currently provided for. They will try to remove all ambiguities. But they must caution themselves in doing so because if the hands of a president is restrained or shackled too much, it could lead a governor as incautious as Mr Fubara to test the constitution to its inelastic limit. The Rivers governor was completely inured to the dangers constituted by his defiance and instigations.

Right from when he allegedly inspired the arson on the legislative building, to when he approved its demolition, not to say his serial defiance of court judgements as he chose which judgements to take and which lawmakers to deal with, it was a mere short walk to constitutional and national security disaster.

He indulged in these provocations because he was sure he had wrong-footed Mr Wike who had been painted as greedy, insatiable and meddlesome. Backed by a sizable percentage of Rivers elders, Mr Fubara paid less attention to fighting his cases in court than harnessing public anger against the Wike camp.

If commentators on the Rivers crisis had been less partisan, they would have seen clearly that the emergency proclamations in Borno, Yobe and Adamawa under the Goodluck Jonathan administration differed markedly from that in Rivers. In the earlier three, they were designed to defeat insurgency or checkmate enemies without. In the 2004, 2006 and First Republic state of emergency proclamations, they were designed to quell internecine political conflicts threatening the republic in the affected states and regional administrations.

In fact, the Dr Jonathan emergency proclamations had no pretext to be called state of emergency. They were nothing more than heightened military exercises heavily supported and bankrolled by the relevant state governments against Boko Haram insurgents. The classical definition of a state of emergency actually involves the suspension of civil and constitutional authorities. If the constitution left the definition unresolved or ambiguous, it is probably because it never countenanced the day when a Mr Fubara or Edo State’s Godwin Obaseki would destroy the legislature, bar lawmakers from doing their work, and instigate the populace in the classical dictatorial sense into taking the law into their own hands.

There was no saving Mr Fubara last week. He should now concern himself with ensuring that he changes his mindset completely away from his natural instinct for autocracy to that of a democrat, even if it makes him a very awkward democrat. His statement rebutting the president claim about his involvement in Mondays vandalisation of pipelines does not show a man willing or capable of learning from his mistakes. He is fixated with Mr Wike, but the latter is not the governor. He is. To hope that the public would continue to conflate their distaste for Mr Wike’s obtruding methods with their support for his rashness in such a manner that extenuates the governor’s authoritarian methods is to chase shadows and doom both his return to office and his first term.

Culled from The Nation