By Emmanuel Oladesu

Almost three years after the demise of Oba Lamidi Layiwola Atanda Adeyemi III, the stool of the Alaafin of Oyo is still vacant, no thanks to royal family squabbles, intrigues, lack of agreement on succession, division among the kingmakers, and government’s directive.

The scramble is not beyond expectation. Alaafin occupies a prestigious position in Yoruba land and Nigeria, and the last occupant had elevated the enviable throne further while upholding the old glory of the empire and legacies of his illustrious forebears.

Iku Baba Yeye Oba Adeyemi III was the bridge between the closing phase of ancient times and modernity, being the first western-educated alaafin trained and equipped for royal assignment.

He fought hard to ascend the throne, assisted by the conservative Oyomesi. His choice as the successor to Oba Gbadegesin Ladigbolu II had the backing of his ancestors and Almighty God.

He was a cultural nationalist; highly knowledgeable about history and tradition. He was fashionable and affable, extending tentacles of influence. He was insulated from the political pressures that created many huddles for his father, Oba Alhaji Adeniran Adeyemi II. Oyo grew in leaps and bounds during his reign, hosting many tertiary institutions and savouring the prosperity of a modern era.

Never shy to make his opinion on national issues known, Oba Adeyemi III advocated a strong local government system and believed in restructuring to foster true federalism.

At the twilight of his life, he undertook the duty of reconciling warring members of the Southwest political elite. But he could not accomplish the self-imposed task before he passed on.

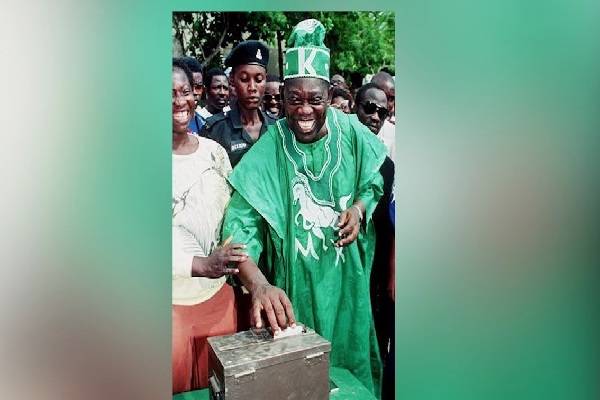

Since Awo and MKO Abiola could not make it to the Presidency, Oba Adeyemi had prayed for the enthronement of a Yoruba son as president. But by the time God answered his prayer and Asiwaju Bola Ahmed Tinubu was inaugurated, he and two other top monarchs – Soun Jimoh Oyewumi Ajagungbade of Ogbomoso and Olubadan Lekan Balogun of Ibadan – had joined their ancestors.

Ibadan’s succession pattern has endured for centuries. Therefore, a new monarch emerged through seniority. In Ogbomoso, a cleric also ascended the throne. Oyo is not that lucky.

Oba Adeyemi was from Alowolodu Royal House. It is therefore, the turn of Agunloye to produce his successor. No fewer than 82 princes contested for the crown. Although it was said that a name was forwarded to the kingmakers, and later to the government, it was disputed by a section of the Oyomesi, which cried foul that due process was not followed.

The Oyo State government, therefore, decided to delay the installation until the institutional framework for the emergence of a new king was followed.

Expectedly, the process shifted to the court.

There is a need for further consultations among the royal house, the kingmakers, and the government for consensus building. The throne should not be vacant for too long to prevent the Ijebu-Igbo scenario whereby a replacement could only be found, 28 years after the demise of Oba Sami Adetayo, Ikupakude IV.

The two ruling houses of Adeyemi Alowolodu and Agunloye trace their roots to Alaafin Atiba, who founded the present Oyo.

Atiba had many children. The two prominent children were Adelu Agunloye and Alowolodu Adeyemi. After Atiba passed on, Adelu Agunloye became the king. After the death of Adelu Agunloye, Alowolodu Adeyemi I became the king.

Adelu Agunloye’s son, Lawani Amubieya Agogo-Ija, became the Alaafin in 1905; he ruled till 1911. His son, Siyanbola Ladigbolu Onikepe, became the king after him. According to historians, because Agogo-Ija’s reign was short, his son, Siyanbola Ladigbolu Onikepe, was asked to succeed him.

Siyanbola was succeeded in 1945 by Adeyemi II, who was succeeded by Bello Gbadegesin Ladigbolu, who died in 1968. There was an interregnum of two years due to royal rivalry.

The number of aspirants to the throne has now increased. Other descendants of Atiba, whose fathers, grandfathers, and even great-grandfathers ( Adelabu, Adesiyen, Adediran, Adejumo, Olawoyin, Tele Agbojuloogun, Ala, Adewusi, Adesetan 1 and 2, Adeleye, Adeotun, Afonja, Agbonrin, Tela Okitipapa, Ogo, Momodu, Adesokan, and Adejojo) never became Alaafin, are trying to press for their rights and asserting personality. It is up to the Oyomesi to resolve the logjam. All the princes are qualified. But only one of them will ascend the throne.

Throughout history, most occupants of the throne have portrayed themselves as true kings of Yoruba and defenders of the race, beginning from their progenitor, Oranmiyan, the grandson of Oduduwa, progenitor of the race.

As makers of history and heads of an empire stretching to the Benin Republic, they shouldered the burden of resisting external aggressors, particularly from the northern and western neighbours, before colonialism finally broke the empire.

The next Alaafin is expected to take after his predecessors in valour, wit, and patriotism. Besides the general expectation that he should be a blue blood, he should also be highly educated and have a vast network. The next Alaafin should also be a mixer like Adeyemi III, a man of colour, immense intellect, and native wisdom. He should be the collective choice of the majority and not an imposed candidate with divisive and destabilising tendencies.

An alaafin should be a unifying factor. He should be willing and ready to work with other prominent natural rulers – Ooni of Ife, Alake of Egba land, Olubadan, Awujale of Ijebu land, Akarigbo of Remo land, Ewi of Ado-Ekiti, Deji of Akure, Osemawe of Ondo, Owa Obokun of Ijesa land ( recently vacant), and Oba of Benin, who is also a descendant of Oduduwa – in articulating the interest of the Yoruba nation within the federation.

In history, the exploits of past alaafins have served as a source of inspiration. Sango was a revered ruler, and his background cemented the diplomatic ties between Oyo and Tapa, his mother being the daughter of Elempe, king of Nupe.

Abiodun has remained the best Alaafin. He ended the rascality of the military leader and Prime Minister in the Old Oyo Empire during the 17th and 18th centuries, Basorun Gaa, and presided over a prosperous kingdom. There was no economic hardship. He ruled with the fear of the gods.

Ajagbo was a creative ruler who created the office of the legendary generalissimo, Aare Ona Kankanfo, to secure the kingdom and defend personal interests. Knowing the implications of what he had done, he decreed that on no account should any Aare wage war against Iwere, where his mother hailed from. He was sure that no Kankanfo would be up in arms against Oyo, the capital.

Atiba was a peaceful ruler, whose son, Adeyemi I, presided over the years of turbulence in Yoruba land. Fed up with the tribal wars, violence, and commotion, Adeyemi I invited the British to intervene in the Ekiti Parapo war between Ibadan warriors, led by Aare Latoosa, and Ekiti forces, led by Ogedengbe of Ilesa and Fabunmi of Okemesi.

As colonialism was winding down, tension arose between traditional rulers and their subjects over the sharing political powers. Such was the case between Alaafin Adeyemi II and Chief Bode Thomas, the Balogun of Oyo.

The rest, as it is said, is history. The colonial lords hijacked power from the traditional rulers and later restored it to the political elite, who first accommodated them as partners in progress but much later relegated them to the backgrounds.

Leaving an ancient town without a head is counter-productive. The supremacy of the constitutional order over the traditional institution is acknowledged, but the performance of a myriad of traditional roles at the grassroots by the royal fathers, including the settlement of land disputes, communal crises, and marital rifts, the preservation of identities, intelligence gathering in aid of security, and general maintenance of order and peace are complementary. If there is a void in these areas, and a particular community is in a crisis, peace across the state cannot be total.

The traditional institution is the cornerstone of the local government system. They are the intermediaries between the government and their people, who serve as channels of communication and enlightenment.

Oyo needs the traditional institution to sustain its position as a respected Yoruba town. The installation of an Alaafin is central to achieving this. The earlier the revered traditional ruler is installed in the ancient town, the better for all the parties in the imbroglio. A peaceful resolution of the matter is urgent and necessary.

Culled from The Nation