By Segun Ayobolu

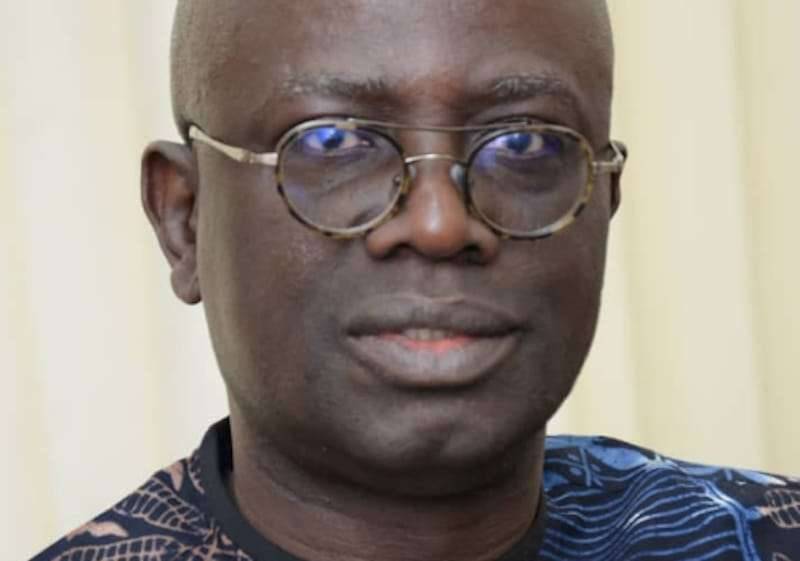

Not only demonstrating his versatility and depth as a trained historian, Sam Omatseye’s recent lecture at the Trinity University, Yaba’ Lagos, titled ‘Information in an Age of Flux’, also vividly illustrated the writer’s rich immersion in the literatures of the world, his philosophical cast of mind, his virtuosity as a technocrat of words and his vast media experience over the last three and a half decades as reporter, editor, columnist, university lecturer in Canada and the US and currently Editorial Board Chairman of this newspaper.

Deploying humour, wit and dialectical reasoning to maximum effect, the Fellow of the Nigerian Academy of Arts exhaustively examines the evolution and transformation of information across time and space within historical, sociological, philosophical and scientific contexts. His lecture is thus essentially cross-disciplinary in range and thrust.

It is understandable and inevitable that Omatseye situates his discourse on the unfolding saga of information in the human experience within the framework of time. It is within the context of time that man lives, works, worships, thinks, invents, entertains, engages in politics, fight wars and dies. Information has become one of the most critical factors in the evolution of man with its influence and impact, both for good and evil, acquiring ever greater significance with the unceasing flow of time.

As the writer evocatively expounds in his opening sentences, “Time and information intersect like twins. We even need information to know time and time to secure information. Hence, the historian is the most important tool to the social scientist. The historian is the custodian of time. If the social scientist needs the historian, memory is the armour of all humans. History is official memory. But our other memory is in our minds and hearts. And time is the only commodity you cannot get back”.

Omatseye waxes poetic as he continues: “Time creates the age. Time changes language, changes leaders, recalibrates culture, overthrows regimes, refines the barbaric into a debonair, makes a monster of a prince or transforms an angel into a Mephistopheles. Time passes like stealth, and it is like death. You cannot resurrect time. You can only imitate or mimic it”. He brings a historian’s microscope to dissect the evolution of societies and cultures from prehistoric times to the present. In his encyclopedic treatise, we are given glimpses into the civilization of the Greeks, the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, the dark ages in Europe, the invention of printing, the acceleration of scientific progress and phenomenal leaps in technological growth particularly information and communication technology and the attendant ever-increasing cultural complexity of society.

The lecturer utilizes the analytic lenses of the sociologist, Alvin Toffler, to dilate on tidal waves of revolutionary change in our contemporary world. In his words, “All of this fall into what Alvin Toffler in his famous book, The Third Wave, called the Second Wave of history. For him the first wave began with the neolithic age, the hunter-gatherer or what some may call the stone age. His categorization may be arbitrary and the content of each category peremptory, but it shows how the mercurial spirit of humanity has spun many a narrative so much so that it takes a lot of work to simplify”.

The lecturer’s thoughts in this regard remind us of the path breaking work of Karl Marx who had earlier delineated progressive stages in the evolution of human society spanning the communal mode of production, slavery, feudalism and the emergence of industrial capitalism in the 18th century. Karl Marx sought to demonstrate that capitalism was not an eternally primordial and preexisting form of the organization of society which was in the natural order of things and thus unchanging. Each stage of societal development, Marx averred, depended on a given level of development of productive forces (technology) and further progress in the advancement of the latter would compel changes in the superstructure leading to higher levels in the mode of organization of society. He thus predicted the ultimate transcendence of capitalism when its extant form of social organization became an impediment to the further development of productive forces at the substructural level, and the inevitable emergence of the communist mode of production.

Ironically, while communism arguably facilitated the rapid scientific and technological progress of previously backward, feudal societies such as the defunct Soviet Union, China and Cuba, within relatively short spans of time, after a point they could not cope with the rate of capitalism’s unceasing transformation of the productive forces of science and technology. China and Russia have thus reverted to market forms of capitalist organization of their economies while retaining essentially authoritarian political systems.

However, the essential import of Marx’s evolutionary analysis of society was succinctly captured by the political scientist, Ellen Meiskins Wood, in her book, ‘The Origin of Capitalism’, when she argues that “The naturalization of capitalism, which denies its specificity and the long and painful historical processes that brought it into being, limits our understanding of the past. At the same time, it restricts our hopes and expectations for the future, for if capitalism is the natural culmination of history, then surmounting it is unimaginable…Thinking about future alternatives to capitalism requires us to think about alternative conceptions to its past”.

Alvin Toffler, however, in his work graphically captures relentless changes in technology that drive unceasing, revolutionary socio-cultural transformation even within the capitalist mode of production. Omatseye paints vivid portraits of these changes in his inimitable style. According to him, “Each age claims that prophecy as referring to their own. When the Wright Brothers gave us the aircraft, they said that was the age of prophecy. And that was before the age of the supersonic jets, the email, the WhatsApp, the Instagram, TikTok, Youtube, the drone, et al. People are going to and fro, not through bouffant clouds in an aircraft. Humans these days are spirits. They can be in a village near Ogbomosho and be in Frankfurt in one minute and Oslo the next and Sydney, Australia and Denver, Colorado simultaneously. You can do a job interview via zoom with a CEO in America, looking at each other while wearing a tie and jacket whereas you are naked from the waist down. Both of you, in American and Nigeria. Yet, you were properly dressed for the interview”.

The lecturer surgically dissects the implications for contemporary society of the revolutionary developments in information technology particularly the emergence of social media and the seeming anarchy of citizen journalism with scant respect for professional rules and regulations. Thus, we see the traditional media having to ceaselessly innovate and reinvent itself to compete effectively and remain afloat. Omatseye also adverts his mind to the immoral and cynical manipulation of information resulting in the prevalence of fake news which is widely perceived as constituting an existential threat to human existence.

The advances in human knowledge as well as scientific and technological growth captured so magisterially by Omatseye has also, in my view, been accompanied by a growing humanistic disposition to life. According to the theologian, Francis A. Schaeffer, “Humanism is the placing of Man at the center of all things and making him the measure of all things”. Thus, he deplores the shift “away from a world view that was at least vaguely Christian in people’s memory (even if they were not individually Christian) toward something completely different – toward a world view based upon the idea that the final reality is impersonal matter or energy shaped into its present form by impersonal chance”.

Implicit in the widespread disbelief in the existence of a transcendental being who created reality and dictated moral laws to guide and restrain human behavior has resulted in what Schaeffer describes as “The abolition of truth and morality”. Situational ethics prevail. There are no absolute standards of right and wrong. Everything has become relative. Politicians are free to lie barefacedly destroying the fabric of trust that is critical to democracy if the end justifies the means. Man’s scientific and technological feats are no longer seen as functions of his being made in the image of his creator who gave him a mandate to conquer and exercise dominion over the earth and equipped him with the innate capacity to achieve this. Within this essentially amoral context, ongoing scientific and technological attainments become dangerous weapons in the hands of a largely flawed humanity.

Thus, Omatseye’s tentativeness is understandable when he submits that “It is probably going to get worse with the new technology known as artificial intelligence, or AI. It is the ultimate mimic technology, as explained in Henry Kissinger’s book, The Age of AI. Anything or anyone can become dispensable. Someone else can present this lecture, if it were done remotely, and pretend to be me, the same face, the same voice. And receive the same applause, the same disapproval. How false that kind of world promises to be? The future is cheery and dreadful. The media is a reflection of the new reality. New reality will be virtual reality. As newspapers are threatened, so is a new world, brave and fragile”.