By Palladium

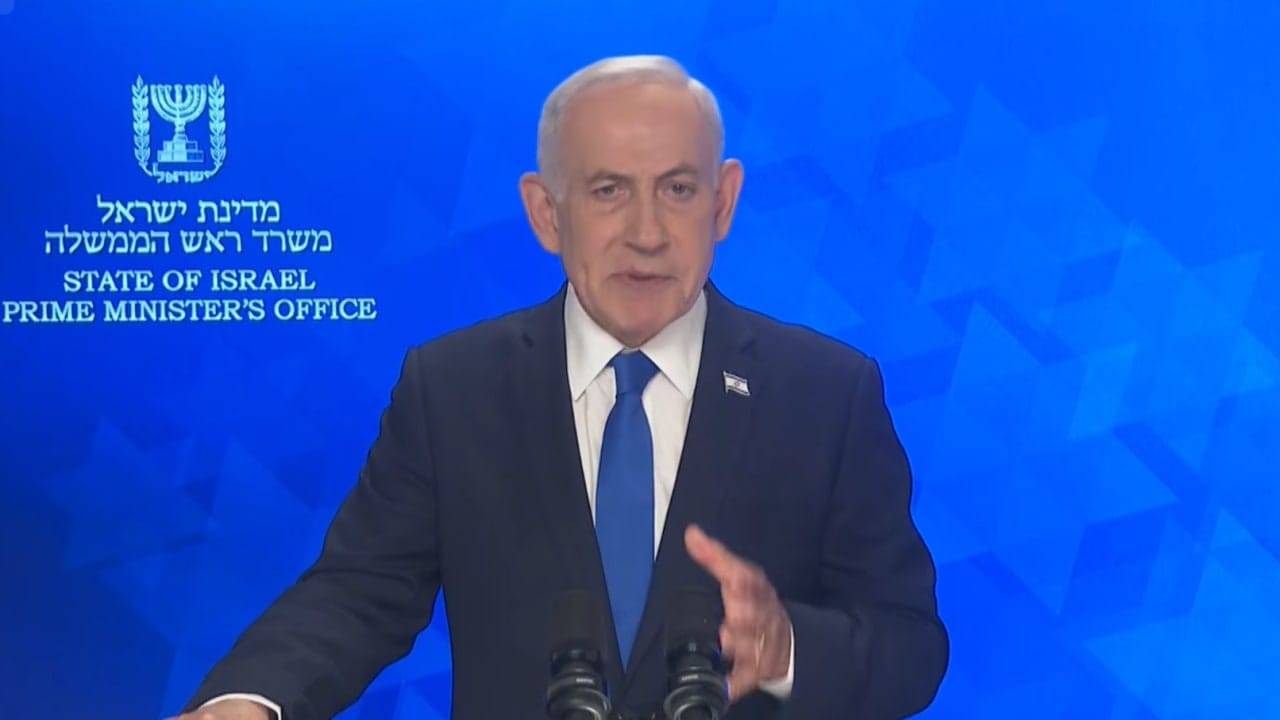

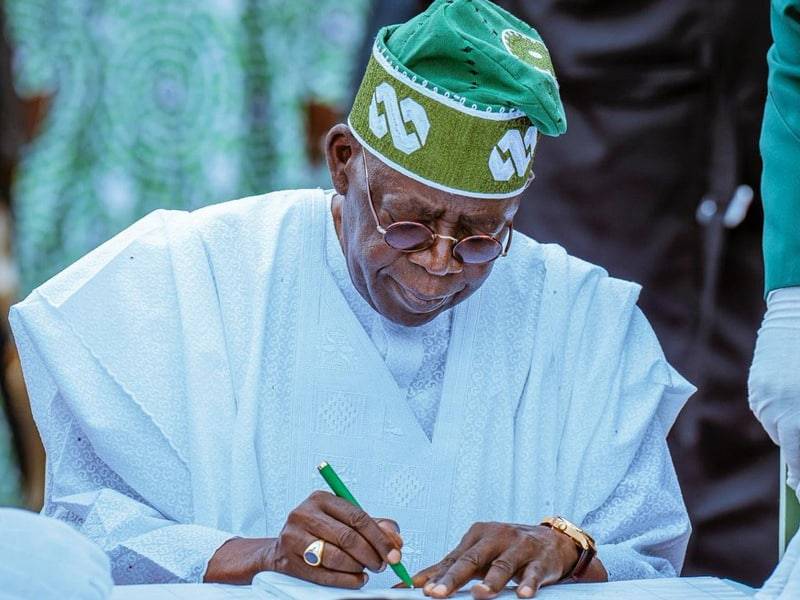

In three days, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu will be one year in office. He will likely be scored low by public commentators, many of them young and impressionable, and Nigerians at the receiving end of the economic turmoil his economic policies have triggered. He has wisely not really commenced his agenda of social and political re-engineering of Nigeria. Tackling the massive rot and stagnation on the economic front has been disruptive enough; adding any other programme to it on a substantial scale would create seismic waves that even he, as stoical and politically adept as he is recognised to be, would be unable to manage. So, largely, he will be scored on how successful he has been in dealing with an economy that, even at the best of times, has been difficult to rein. In the past one week, his ministers have made heavy weather trying to burnish the administration’s scorecard. They have not been very successful, especially with inflation resistant to control, exchange rate unamenable to the Central Bank of Nigeria’s best efforts, insecurity yielding a yard and taking back a foot, and the administration itself quite unable to get its act together as manifested by disquieting reversals in varsity council appointments, tax policies, and expatriate employment levy, among others. Indeed, fewer Nigerians are optimistic that his economic reset agenda will yield fruit in the near future.

But the reason a presidential term is four years is to give room for rebuilding foundations, setting building blocks properly, and constructing durable economic and political edifices. The period also allows for missteps, some inconsistencies, even if fundamental, and the rethinking and rejigging of sundry but impactful policies in all areas of national life. The harshness and rapidity with which the Tinubu administration has been judged in the past few months, despite the four-year term provision, may not be unconnected with the manner of his emergence and the controversies that smothered the last elections. The country is largely divided along ethnic and religious lines, and divisive champions, given fillip by a giddy and obstreperous social media, have had a field day. Those passing judgement will not wait for his term to end before sentencing him; they will continue to harry his administration and hope he will be flustered and susceptible to mistakes. Those who don’t like him will continue to loath him whatever he does. And those who love him will have their faith tested severely on account of the trenchancy and widespreadness of his critics.

On Wednesday, the Tinubu administration will be one year in office. But consumed by either hatred for his person or loathing for his economic and financial policies, some Nigerians may have failed to appreciate the biggest value of the administration in the past 12 months. Far beyond his economic policies, some of which may be misplaced or even conflicting, and far beyond his tentative social and political reengineering of the republic, is the great service to national unity and cohesion which his election and inauguration have occasioned. That Nigeria is still standing today and not embroiled in anarchy or, worse, war, is an acknowledgment of the calming effect the election of an ‘outsider’ has brought upon the country. At first consideration, he was the most suitable for the presidency among the three leading aspirants who vied for the presidency in 2023. Electing former vice president Atiku Abubakar would have elongated and perpetrated Fulani rule over Nigeria after eight years of President Muhammadu Buhari. It would also have entrenched the hegemony of the uniformed services. Electing the flighty and clearly unprepared and opportunistic Peter Obi would have jeopardised the stability of the country for many reasons, chief among which was his capacity for politicising religion and his predisposition to becoming a hostage to powerful interests and his militant supporters.

By 2022, many Nigerians, including some who are close to the president today, had concluded that after former president Goodluck Jonathan’s inimical administration, the North would not relinquish power. That self-defeatist sentiment was predominant in the PDP and nearly the entire South, including the Southwest; and given the insularity of the Buhari administration, it was widely believed that he would certainly not hand over to a southerner. Worse, it was also affirmed in many quarters that the military would rather let a paramilitary officer take office than a ‘bloody’ civilian. Then, there were the two clinchers suggesting that Asiwaju Tinubu was the most hated politician of the time, a man described as so inflexible as to be unamenable to control and discipline, and that the electoral and arithmetical dynamics of Nigerian elections did not conduce to the victory of someone not sponsored by the ‘owners of Nigeria’, or the massive votes of the North, or the support of the two main religions. President Tinubu’s victory shattered myths and preconceptions, and like MKO Abiola’s election in 1993, opened the gates for a robust civilian or a southern secularist to win the presidential election on his own merit and by dint of his own permutations. The election and one year in office reinforce self-belief in political aspirants that victory is possible if they play their cards adroitly.

The 2023 presidential election may to a large extent have destroyed the hegemonic proclivity of the North which had before the poll promoted and embraced northern and military exceptionalism. President Tinubu’s inauguration, despite calls for a preemptive coup d’état or celestial intervention to murder him, may gradually begin to nurture in the North a feeling of living and letting others live, and a feeling that the idea that one group owns Nigeria is atrophying. In four years, and possibly eight, the idea of inclusive politics may begin to take root in the psyche of Nigerians, infusing confidence in anyone bright and bold enough to aspire to the highest office. In the years ahead too, neither the Yoruba nor the Fulani, nor yet the Igbo, among other ethnic groups, would propagate the conviction that one group owns the rest. It may take a little more time to deracinate the poisonous and retrogressive roots of Islamic fundamentalism and evangelical fervour in Nigerian politics, and a few more years before the last gasps of military obtrusion as exampled by the Okuama misadventure and Abuja Banex Plaza profligacy are heard. But, clearly, the Tinubu election and presidency, not to say his bold and independent though sometimes conflicting and ineffectual policies, have reinvigorated the tentative belief in the concept of Nigeria.

President Tinubu may not have got or done everything right in his first year, but he has been an unheralded instrument for the rethinking, regeneration and renewal of Nigeria. There is thus a celestial tinge to his presidency. His main ministerial cabinet may have been a mixed multitude of the brilliant and the comical, and his kitchen cabinet a little worrisomely uninspiring and devoid of a steely and coherent core, but it will be a mistake to use these partial failings to define or obfuscate the real value of his election and administration, not to say his one year in office. Some analysts, using the precedent of his stewardship as governor in Lagos, have described him as a slow starter. There is nothing to be ashamed of regarding his speed. What matters is that in his second year and third, he needs to pick up speed in terms of the outstanding existential issues assailing Nigeria, and to consolidate in those things in which he has shown great promise. He will be pressured to deliver a restructured country, a peaceful country cranked into life by a political engine that is well oiled and serviced. He has not shown a lack of courage in his first year in office; but it is now time to demonstrate that intuitive and almost metaphysical grasp of the possible that galvanised him into office last year. Kano and Rivers in their kingship battles and godfather complex respectively have shown a disturbing predilection for dictatorship, if not messianic complex. However, especially in light of the agitation for state police, President Tinubu has a duty to rein in bungling and combative governors before they begin to govern their states as if they are independent republics devoid of the rule of law and are accountable to no one. The next elections may have crossed his mind, and many around him, particularly the obsequious, may begin dropping hints; he will do well to resist their blandishments and instead focus on the urgent task of rebuilding the country’s economy, politics and self-esteem battered by poor leadership and tyranny.